The Tender Trap Part 2: The Winner Takes It All (beyond procurement)

By

Ian Harris and Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Charity Finance, Plaza Publishing Limited, pages 40-41.

Professor Michael Mainelli and Ian Harris, The Z/Yen Group

[An edited version of this article first appeared as “The Winner Takes It All” (tendering), Charity Finance, Plaza Publishing Limited (February 2008) pages 40-41.]

Charities increasingly find themselves required to tender in order to win public sector contracts. Similarly, charities increasingly require their suppliers to go through structured tendering processes. But often those structured tendering processes are inappropriate for the procurement situation, helping neither the buyer nor the sellers. In this second of two articles for Charity Finance, Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli of The Z/Yen Group examine “The Tender Trap” from the perspective of charities who sell their services. [See Part 1]

I Don’t Want To Talk About The Things We’ve Gone Through

Charities are increasingly adopting “public procurement”-style processes when purchasing; that was the subject matter of the first Tender Trap article (Charity Finance, December 2007). Yet charity people often complain to us about the unreasonable and inappropriate demands of the public procurement processes required of them to win public sector contracts. This Tender Trap article discusses competitive tendering from the point of view of charities as sellers of services.

While we grab another opportunity to recycle a well-known song title and its lyrics, public-sector tenders often have very little to do with winning people winning at all.

We shall provide some guidance on how to qualify your opportunities to tender, such that you will hopefully decide not to bid on appropriate occasions. And for those occasions when you decide to proceed with a competitive tender, we provide guidance on how to identify the key decision maker(s) in the process.

The Winner Takes It All, The Loser Has To Fall

The principle of winner’s curse is that in a competitive tendering situation, where the competitors have incomplete information about the exact costs and/or value involved, the “winning” competitor nearly always under-prices their bid, such that the “winner” is eventually disappointed. The disappointment might not be actual losses (although in many cases, on a full-costing basis it does result in real losses) but it does result in a lower than expected return. One intriguing and somewhat counter-intuitive element of the winner’s curse is that the larger the number of participants in the competition, the more pronounced is the winner’s curse effect.

While economic theory suggests that rational contestants should price “known unknowns” into their bids, experimental situations demonstrate that participants can be familiar with the phenomenon of winner’s curse, yet repeatedly make the same mistakes in subsequent experiments. In the real world, we often see the same contestants caught out by the winner’s curse in fields such as mergers and acquisitions (they rarely add value), auctions of scarce resources (for example the 3G bandwidth auctions).

While we might tut-tut at corporate executives hubris and/or anomalous decision-making behaviour, in many ways the phenomenon is even worse when experienced by charities. Charities (perhaps unwittingly) frequently disguise their winner’s curse losses through hidden subsidies from donated funds on contracts that are supposed to be fully-funded. This is often hidden in overheads or infrastructure costs, where large public sector contracts (supposedly fully-funded) often put a substantial strain on already stretched charity resources.

Where there is significant competition for a public service contract, charities should be asking themselves very serious questions about why they should bid. If a commercial provider is willing to provide the services to a specified, requisite quality and the public sector is required to pick up the cost of that service, why should a charity bid to do the same thing for less money? If several organisations are bidding for the contract, it is even more likely that the winner of the contest will be underpaid for the service. What benefit is such a “win” delivering to a charity’s objectives?

But I Was A Fool, Playing By The Rules

Of course, there is no rule that says you have to bid for every opportunity that potentially falls within your “patch”. Indeed, in our view, one of the most likely reasons for people bidding in inappropriate situations is the mistaken belief that you need to assert your territory whenever a contract comes up in your field of work.

As adherents of our own advice, at Z/Yen (and many of our clients) assess opportunities using a “Bid/No-Bid Decision Matrix”, with which we assess the factors relevant to that critical decision – should we bid or not. A great many competitive opportunities fail to make the grade on the basis of this assessment. Naturally, the relevant factors vary from organisation to organisation. The following table is an extract from the Bid/No Bid Decision Matrix for a fictitious charity, For Pity’s Sake Care Services, which provides domiciliary care for the needy.

Table One: Bid/No-Bid Matrix for fictitious charity “For Pity’s Sake Care Services”

| Bid/No-Bid Decision Matrix | Opportunity: | Ref: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bid Factors | Bid Factors Scoring Range | |||

| Low (0-3) | Medium (4-6) | High (7-10) | Score | |

| Relevant experience | Core | 7 | ||

| Availability of resources | Average | 5 | ||

| Overall capability | Superior | 7 | ||

| Strategic Importance | Moderate | 6 | ||

| Emerging Need | Very much so | 8 | ||

| Urgent Need | To some extent | 5 | ||

| Key beneficiaries | Not really | 3 | ||

| Many beneficiaries | Many | 7 | ||

| Our offering unique | No | 3 | ||

| Value of “marker” bid | Reasonable | 5 | ||

| Contribution | Full cost cover | 6 | ||

| Customer relationship | Well known to us | 7 | ||

| Competition | Open | 5 | ||

| Bid resources | Sufficient | 6 | ||

| Number of bidders | 3 or fewer | 6 | ||

| Market intelligence | Thorough | 8 | ||

| Total Score (Bid threshold 80) | 94 |

In our experience, you need to set the bid threshold reasonably high, as the winner’s curse phenomenon combined with the natural optimism of enthusiasts leads most people to over-rate rather than under-rate opportunities when using this type of matrix.

Remember to revisit the Bid/No-Bid Matrix if the goalposts move, which they very often do in these tendering processes, and be prepared to quit if the numbers no longer stack up for you. Don’t make the mistake gamblers often make of being sucked deeper in to a game than intended – cut your losses by withdrawing from a winner’s curse bid.

The Judges Will Decide, The Likes Of Me Abide

For some forms of vital work there is little or no alternative to tendering. But when you do tender, you want to know as much as possible about the competition and the decision-making process. The “Bid/No-Bid Matrix” is actually a good discipline for finding out as much as you can about the process.

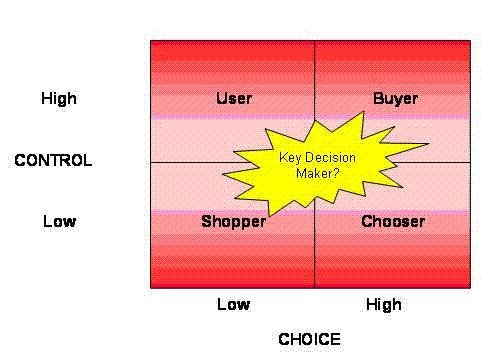

There is one aspect of the competitive selling situations that we consider to be vitally important although it is often overlooked, which is “who is the key decision maker”. In the late 1980’s we both worked for a firm that used the phrase BUSCK – “buyer-user-shopper-chooser-key decision maker”, a phrase that has always resonated with us. We cannot find a reference for it (so apologies to anyone who deserves credit for inventing BUSCK), but in any case the following diagram and text that follows is our own take on this form of analysis.

Diagram 1: Buyer–User–Shopper–Chooser–Key Decision Maker (BUSCK)

In theory a buyer has a great deal of control over the purchasing process and can spread the procurement net widely or narrowly. A shopper, on the other hand, while they might make on the spot decisions, is probably not controlling the procurement process and is probably only looking at choices within the constraints of options presented to them. A chooser is often a professional procurement person (sometimes an external consultant) who might ensure that the appropriate range of choices is presented but might have little control over the decision making beyond that. A user is the person or people who, on the other hand, might have a great deal of control over the procurement process (e.g. substantial input into writing the specification) but often has little input to the choices that are eventually made.

Of course, in many cases one individual fulfils more than one of those four roles. If one individual fulfils several of the roles, you might well have identified your key decision maker. But when the roles are well spread between several individuals, it can be very difficult to work out who the key decision maker is. Only occasionally does the decision really get made collectively by a selection panel; more frequently than you might realise there is a key decision maker who ultimately makes the decision. If you are speaking that person’s language you are more likely to win, so it is extremely helpful to at least try and identify who that person is and what will motivate them to select you.

It is important, where possible, to have formed your BUSCK assessment some time before the invitation to tender drops into your in-box. Ideally you want those prospective clients to know you well enough that they are only going to invite you to tender in circumstances which are genuinely suitable for both parties. And of course you would like the proposal to play to your strengths, which is all the more reason for you to seek dialogue before the specification is finalised.

But You See, The Winner Takes It All

To summarise this second part of the Tender Trap, here is another mini manifesto, this time for the selling side of the charity:

- the sweetest bid of all is often not to bid – remember how often the winner will suffer from winner’s curse. Winner’s curses (unlike sour grapes) are best savoured when you’ve not bid at all;

- know when to quit a tendering process, especially if the goalposts move in an unfavourable direction during the process;

- ensure you have enough information about your prospective clients to minimise the risk of winner’s curse in your case;

- bid when tendering processes should favour you, i.e. when you know that key decision makers at the prospective client are inviting you to bid, because they know that you actively seek such work and that you should be well-equipped to do the work well.

Ian Harris and Professor Michael Mainelli are Directors of Z/Yen Group Limited, a risk/reward management practice, dedicated to helping organisations prosper by making better choices (www.zyen.com). Z/Yen clients include blue chip companies in banking, insurance, distribution and service companies as well as many charities and other non-governmental organisations.