Small Enough To Fail: A Systems Approach To Financial Systems Reform

By

Professor Michael Mainelli, Bernard Manson

Published by Journal of Risk Finance, Volume 12, Number 5, Emerald Group Publishing Limited (October 2011), pages 435-444.

Abstract: The financial crises since 2007 have inspired many suggestions for reform. In order to evaluate proposed changes to financial markets and their regulation, we need to agree on the goals and properties of the financial system which we are trying to create as much as come up with ideas for reform. This paper looks at how design principles might inform financial systems design. It presents a sample set of principles based on a structure that distinguishes Insured Banks from Other Financial Institutions.

Keywords: systems theory, financial regulation, banking reform, utility banking, narrow banking, insured banking, diversity.

Introduction

The ‘Credit Scrunch’ of 2007 was a systemic failure. Interactions between elements of the system (banks, rating agencies, regulators, governments, financial instruments, etc.) mattered more than the specific behaviour of a particular actor. If you believe the crisis was an apocalypse or foreshadows an apocalypse, then you should be considering fundamental reform. You want to redesign, and design principles would be handy. What might they be?

Systems Theory, touching on if not encompassing chaos theory and complexity theory, gives us a rich background to some simple design parameters, viz. input-process-output, governance, monitoring, feed-back and feed-forward. Systems Theory goes some way to explaining why financial systems, due to their large amount of feed-forward (positive feed-back), tend to exhibit ‘fat tail’ outcome distributions and more instability than physical systems. Bob Giffords, the technology analyst, groups together feed-back, monitoring, feed-forward and governance components as “feed-through”, highlighting the effect of people’s perceptions on the probability of future events. [Mainelli & Giffords, 2009] If people change their perception of a risk, e.g. terrorism, that perception feeds through to alter future behaviour, such as passenger levels on public transport. Systems with feed-through – and human systems are marked by this - typically have non-normal event distributions. Systems theory suggests that, for the sake of resilience and robustness, larger systems should be broken into smaller, more discrete and redundant systems where possible. Feed-through suggests a need to slow processes down and introduce variety, leading to recommendations for countercyclical mechanisms, but oddly perhaps considering slowing down or breaking up information flows.

Purposeful Design and Redesign

A huge number of initiatives are underway; some seemingly uncontroversial, some already showing signs of unexpected consequences, and some mutually at cross-purposes – Dodd-Frank, IMF, Turner Review, UK Independent Banking Commission, Walker Review, Warwick Commission, G30, Bank for International Settlements, etc. Modern finance is a hugely complicated system, in which neither the regulator nor ‘the market’ guarantees safety. Jean-François Rischard of the World Bank rightly warns of ‘excessive trust in the market, and the complacency that results from it’. It takes modesty to admit that one doesn’t really understand the system and doesn’t know how to fix it by tinkering with a few parts. Piecemeal reform misses key reforms and induces contradictions. “At the moment, governments are wading in with all kinds of levies and regulations, which will probably have unintended consequences. Rather than tackle the big problem (for example, by breaking up the banks), they waste their time on populist measures like banning short-selling.” [The Economist, “Buttonwood: Time For A Rent Cut”, 5 June 2010, page 86]. Equally, regulation has limits of effectiveness and real costs [Briault, 2009].

The Long Finance initiative’s challenging question, “when would we know our financial system is working?”, prompts us to define purposes of parts of the financial system as statements, such as “the financial system’s purpose is to transfer money and hold cash deposits while maintaining consumer confidence”. This last statement may seem rather modest, and it is easy to create statements of broader scope, such as “to provide a 20 year old with a suitable financial structure for his or her retirement”. So one of our first suggestions would be to add to regulatory reform deeper discussions of the defined purpose of the reforms.

We start with the presumption that a designed system should have a defined purpose, otherwise there is little certainly that a useful purpose will be achieved. If we want to be able to design from a set of ‘first principles’, a basic approach is to define goals and to identify key structural requirements to achieve these. These requirements are then encoded as principles, which are used to evaluate the design of individual system components and subsystems. As a simple example, in planting forests for sustainable growth, goals might include protection against preventing forest fires or overwhelming loss from disease. Recognising that there will always be fires and diseases, this could lead to design principles of firebreaks and the planting of multiple species. Similarly, in electrical systems, components such as isolators, fuses and cut-outs prevent individual circuit failures crashing the whole system. From medical thinking, we seek isolation wards, inoculation and barriers to prevent contagion spreading. From other system designs we seek alerts, firewalls and crumple zones. We design transport systems to minimise the chance of crashes, but we also design vehicles to make crashes survivable.

If it is possible to split a system into independent subsystems, what benefit or disbenefit will be achieved? In 1973, E F Schumacher wrote a series of essays, Small Is Beautiful: Economics As If People Mattered, which challenged accepted economic ideas, such as the benefit of scale. Schumacher promoted decentralization, regionalization, improving quality of life, and minimising social dislocation. In parallel, he recognised the importance of ‘smallness within bigness’, the idea that large organisations need to emulate the virtues of groups of small organisations.

Environmental assumptions are also significant. One environmental assumption might well be that there will always be booms and busts. Bubbles supposedly reflect irrationality. However, they may also reflect rationality. People always have to act with limited information, so behaving like everyone else may be the best available simple rule. These ‘herding’ processes drive financial systems, for example price setting, so that small changes in beliefs can result in large changes in prices. If bubbles cannot be eliminated, the goal of financial markets reform should be to contain bubbles in a manageable way. Based on the assumptions that bubbles exist, we could state one control goal as:

‘After a mega-bust, maintain a functioning financial system with minimal state subsidy.’

We might state our control goal in a more detailed way:

Problem to solve

‘How should we legislate and regulate so that:

(a) failure of one financial institution will not bring about the failure of others (contagion)

(b) failure of a financial institution will not create material losses for a large class of innocent individuals (mass individual losses);

(c) failure of a financial institution will not create a large direct loss to the government or taxpayers (state loss)?’

This statement differs markedly from current practice. For example Basel rules often encourage inter-connectedness among financial institutions – “too interconnected to fail” – as well as erecting barriers to entry and exit that encourage – “too big to fail”. In Basel 1, risk weightings encouraged banks to lend to other banks and sovereign governments. 0% risk weightings increased leverage, thus increasing the impact of failure. Current Basel proposals still give large offsets to government lending, increasing concentration on government debt and adding leverage to that market and banks. There could be many other control goals for other parts of the financial system, ranging from the small to the large, from the wide to the narrow, e.g. “being able to evaluate the quality of audits”, “during a crisis, having the ability to recapitalise banks quickly”, “preventing insurers from selling below their long-term ability to underwrite”, or “protecting consumers from products they are unable to evaluate”.

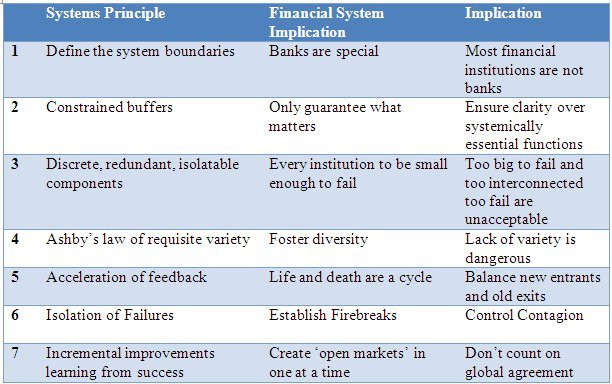

What design principles, if implemented, might constitute a solution to the problem above, ‘after a mega-bust, maintain a functioning financial system with minimal state subsidy’? We don’t propose Ten Commandments or Six Easy Pieces or any particular number. To initiate discussion, seven principles, a ‘starter set’, are set out in Table 1, followed by some explanatory notes for each principle. Because the unprecedented size and cost of the 2008 crash arose from the perceived – ex ante as well as ex post - need for governments to bail out the financial sector, this suggested starter set of principles is heavily biased towards creating a recognised area of low risk for retail customers.

Table 1 - A Starter Set Of System Design Principles

Principle 1: Define The System Boundaries – Banks Are Special - Most Financial Institutions Are Not Banks To provide the required robustness there should be a spread of financial institutions, some with greater freedom to grow or crash, others more tightly regulated. For the less regulated, the key goal is that they can fail without systemic knock-on effects. By minimising the attractiveness of special status, i.e. implicit government support, we should minimise the number of tightly regulated institutions. Further, by requiring them to be structurally simple, it becomes more practical to have regulation which works.

We distinguish wholesale banking from retail. ‘Retail’ financial institutions perform basic functions: money transfer, deposit taking, deposit interest and lending. Investment banks, or ‘wholesale’ banks, “create and trade complex bundles of promises and property rights” [Morrison and Wilhelm, 2007, page 97], typically in mergers and acquisitions, securities issuance, and trading. If wholesale banks go bust their employees can recreate much of their core functionality quickly in a new entity, in contrast to retail where scale is key. Failures or prospective failures in wholesale banking, foremost Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, were a key stage of the financial crises. Governments extended the retail banking rationale for state support of wholesale financial services – that in order to prevent bank runs, failures should not hurt ‘Main Street’ or ‘High Street’ confidence – to wholesale bank, justifying virtually limitless support for all financial services.

We propose splitting financial institutions into Insured Banks and what we unimaginatively term Other Financial Institutions (‘OFIs’). The core institutions are ‘Insured’ Banks because their money transfers and cash deposits would be insured by governments. There are clear similarities to other proposals of ‘narrow’ [Kay, 2009] or ‘utility’ banking, as well as to the twin regulatory structure proposals of marketing fairness boards for consumers versus investment boards for wholesale participants [Taylor, 1995, 1996].

There is a large grey zone between a very narrow interpretation of ‘Insured Bank’, with just money transfer and non-interest bearing deposits, and the conventional interpretation of a retail bank where interest-bearing deposits and domestic lending are included. Because the financial system recycles funds between different sectors of the economy and between different maturities, the economy could only function in a traditional manner if Insured Banks have OFIs that provide services such as interest-bearing deposits, domestic lending and corporate lending. Insured Banks should have a very low maturity mismatch, and thus be far less likely to cause systemic problems. Further debate could lead to Insured Banks having a bit more leeway but, the larger the scope of their services and the more maturity mismatch permitted, the tougher it will be to build robust designs.

The regime for Insured Banks would aim at keeping the system as a whole intact and reasonably well capitalised after a bust, although individual Insured Banks might fail. Insured Banks would be required to offer, at a price, a ‘risk free’ deposit and money transfer facility, where customer funds would be collateralised by government debt. Insured Banks would be more expensive than current banks, but there would be clarity about where people took risks with their money. For example, today one cannot realistically insure against a bank going bust just after a single large payment – say a house sale – arrives in an account. For an individual, such transactions are rare; for some small businesses, they can be weekly. If trust in banks vanishes, such transactions could become impossible. Under the Insured Bank regime, individuals and businesses would pay more to gain the clarity of the guarantees of the Insured Bank. Such a regime would implicitly encourage OFIs to take more risk than Insured Banks, so that they could offer lower costs and better interest, but with clarity over risk. For debate? Gearing, use of securitisation, use of derivatives, credit exposure; in short, many things, and most importantly whether allocation of credit and transformation of short-term deposits into long-term loans is within the scope of Insured Banks.

Principle 2: Constrained Buffers – Only Guarantee What Matters – Ensure Clarity Over Systemically Essential Functions The economic and political minimum is to provide guarantees – possibly for a fee – for money transfer and deposits. This minimum should also be the maximum.

The sole areas of the financial system with zero tolerance for failure are:

- the clearance system – the ability to pay funds from any bank account to any bank account with 100% safety;

- the ability of individuals or organisations to hold transactional funds with 100% safety. Therefore, the Insured Bank structure should ensure that, in addition to robust regulation, there is an explicit guarantee available for these services. Given the nature of the clearance system, the state will ultimately have to guarantee that all funds leaving Bank A will arrive safely at Bank B. However, for transactional funds an Insured Bank should be able to provide 100% government debt collateral.

In a second area, occasional failure is acceptable, provided there is only a small loss to any individual: the ability of individuals to hold funds of reasonable size as deposits with, say, guaranteed 95% safety (i.e. the individual will not lose more than 5% of his or her principal). To prevent the failure of an insured bank creating a material loss for a large number of ‘innocent voters’ there should be deposit insurance for retail deposits up to a maximum size (to include transactional funds), implemented by a mutual insurance scheme and bolstered by insured depositors being preferential creditors; however, the scheme would require the state as ultimate underwriter. To prevent the failure of an Insured Bank creating a large loss for the state, regulation will need to require Insured Banks to have reduced gearing and to hold assets tending to behave linearly.

Principle 3: Discrete, Redundant, Isolatable Components – Every Institution To Be Small Enough To Fail – Too Big To Fail And Too Interconnected Too Fail Are Unacceptable The test here is whether the state would perceive an obligation to rescue the institution with state funds. If the answer is ‘yes’ or ‘maybe’, the institution is too big (noting that ‘too big’ can arise from a combination of size and complexity). The system should stop such institutions coming into being, and should break them up if they do.

In a global economy of approximately $55 trillion GDP Professor Niall Ferguson noted in The Daily Telegraph: “By the end of 2007, 15 megabanks, with combined shareholder equity of $857 billion, had total assets of $13.6 trillion and off-balance-sheet commitments of $5.8 trillion – an aggregate leverage ratio of 23 to 1. They also had underwritten derivatives with a gross notional value of $216 trillion – more than a third of the total.” [“There’s No Such Thing As Too Big To Fail In A Free MarketF”, 5 October 2009] One must add to these a few other large organisations such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and AIG, but fewer than two score organisations were at the centre of the Credit Crunch. Today, with total banking assets of the top 1,000 banks in the world of about $95 trillion, the twelve largest banks control about $20 trillion - an amazing concentration.

Unless regulators have a credible threat to close a bank down, they cannot impose their will; too big to fail becomes too big to regulate. Between 1986 and 1995 in the Savings & Loans debacle, the USA let 1,700 of 3,400 entities go down, at a cost of $125 billion. At points over the past two years governments have been spending $1.25 trillion a month trying to keep large organisations together. Closing them down appears not to have been an available option. Regulators need a ‘nuclear’ option, pulling a bank’s licence to operate. Current suggestions for 'Living Wills’ to ensure that there is clarity on which legal entity inherits each asset and liability are useful, as is the regularisation of stress testing.

Removing explicit and implicit state guarantees except for Insured Banks, is only one step towards establishing a structure where no financial institution is ‘too big to fail’. OFIs should be lightly regulated or close to unregulated, but policy should dictate that no OFI is permitted to be too interconnected or complex to be allowed to fail. As John Fingleton noted, “History tells us that restricting competition can look attractive to policymakers faced with a distressed business in a recession.” [“Financial Groups Must Still Be Free To Compete”, Financial Times, 17 April 2009] So, competition policy should be enforced, but this won’t be enough. Supervision, knowing what’s going on, will be important in order to avoid situations such as the concentrations of CDS protection at AIG. Supervision should focus on identifying too much inter-connectedness. Even then, controls on market concentration will need to be conservative. Northern Rock in the UK was not, in 2007, seen as too big to fail. Regulation should focus on keeping Insured Banks safe. The UK, with 4 banks holding some 80% of the retail and commercial banking market, will be an interesting test case for breaking up banks which are currently too big to fail.

Principle 4: Ashby’s Law Of Requisite Variety – Foster Diversity – Lack Of Variety Is Dangerous We need to encourage firms to have a range of behaviours. In a crash, identical banks tend to collapse at the same time – making irrelevant the fact that each individually was small enough to fail. Homogenous regulation induces homogenous firms. Regulation should stimulate different behaviours among firms, so that when the bust comes some will perish and some survive.

Ashby’s Law, originally from cybernetics, states that the amount of appropriate selection that can be performed is limited by the amount of information available; and that for appropriate regulation the variety in the regulator must be equal to or greater than the variety in the system being regulated. Or, the greater the variety within a system, the more regulation will reduce its variety. Regulators are ‘homogeneity inducers’; centrally imposed requirements such as minimum capital or professional job requirements tend to make organisations act alike. Similar pack behaviour can arise from self-organised standardisation, for example in technology – Excel, risk management software, or anti-money-laundering software; an embedded error or bias in any of these could have systemic impact.

Regulators should have an objective of stimulating diversity among financial institutions. After regulators make sure that their markets are competitive, we need to give regulators targets for a vibrant market. Give them targets that measure ‘bio’ diversity in their markets as a counter to too much regulation.

Principle 5: Acceleration of Feedback - Life And Death Are A Cycle – Balance New Entrants And Old Exits Competition requires failures and success. The financial system must allow institutions, including Insured Banks, to fail. There also needs to be provision for creation of new financial institutions to fill gaps, and to allow institutions which become too big to be split.

Regulation should ensure that institutions are always ‘small enough to fail’ and that Insured Banks which do fail will almost always ‘fail smooth’, that is they should be able to repay a substantial proportion of liabilities on winding up. A key design feature is that in a boom and bust we want to allow individual OFIs the right to fail spectacularly. History suggests that some OFIs will fail, thus acting as an early warning for other institutions. Failing banks are an important feedback mechanism, yet cause and effect are not always clearly linked in time, so the lessons we learn for redesign are often tentative.

We would like regulators to explore targeting entry and exit numbers to ensure healthy, competitive markets, and to promote feedback. This contrasts with the current interpretation UK regulators apply to ‘market confidence’ and ‘financial stability’, statutory objectives 1 and 3 of the Financial Services Authority. They interpret this as avoiding firms failing, thus not applying anti-trust or anti-monopoly legislation [McElwee and Tyrie, 2000].

We do not underestimate the difficulty of creating a new Insured Bank, especially given the inertia of customers and the operational overhead of building a customer base of appropriate scale. We would see one approach to this as encouraging or requiring banks to share operating platforms and branches, open-access requirements similar to those used in telecoms regulation. This contrasts with existing impediments to access to foreign institutions at many national payment systems. More rapid creation of Insured Banks would require forcing existing banks to both slim down, thus shedding infrastructure for new entrants, and forcing existing banks to split Insured Banking operations from OFI operations, even if the Insured Bank and the OFI were within the same holding company structure.

Principle 6: Isolation of Failures – Establish Firebreaks – Control Contagion Preventing failure of one institution causing the failure of another requires limits on exposures between financial firms. These should be strict for Insured Banks, and progressively less prescriptive for OFIs. Limits should include intra-group limits and limits on total exposure to other financial institutions, as well as restrictions on short selling financial institutions’ shares.

There have been numerous informed suggestions in this area, several of which we would support. However, we would also want some straightforward limits on the assets an Insured Bank can hold which represent claims on other financial institutions or on foreign governments. One big complaint will be that firebreaks and additional backups that tie up capital render the system less efficient. But efficient capital utilisation is not an over-riding goal. With ‘the net present value cost of the crisis at anywhere between one and five times annual world GDP’ [Haldane 2010], complaints that reforms throw away ‘highly efficient’ capital utilisation seem to ignore the genuine costs incurred in repeatedly saving the system

Principle 7: Incremental Improvements Learning From Success – Create ‘Open Markets’ In One At A Time – Don’t Count On Global Agreement Inter-government agreements are difficult to achieve, unwieldy, and apt to unwind if they require transfer payments; we therefore need to design solutions that can be implemented within one country without breaking existing international commitments.

“Some commentators are beginning to realise that after over two years of reform activity, there has been virtually no reform. There are some interesting suggestions that any reforms needed any time soon should be done at a national level.” [Rottier and Véron, 2010]. “Watching the world’s regulators rewrite the rules of finance is a bit like supporting toddlers in an egg-and-spoon race. You want them to get to the finishing line but for every step forward there is a fumble, a squabble and lots of milling about.” [“Regulating Finance: Patchwork Planet”, The Economist, 2 July 2011, page 68]

Governments are, and will be, unwilling to pay to support banks in other countries. The swiftest action in the event of a bank failure can be achieved by developing Insured Banks on a national basis. Only the domestic government pays out money transfer or deposit insurance, principally to domestic victims of money transfer or deposit losses. OFIs getting into difficulties will, obviously, have no right or expectation of rescue.

Conclusion - Selling Real Principles

The above principles are merely examples. One could suggest that a set of design principles are unnecessary. This view might hold that the financial crises were ‘business failures’ and need no correction. There are some heroic arguments that perhaps no regulation at all is needed [Arthur and Booth, 2010]. Exploring radical paradigms is helpful, but in the end change must be socially and politically acceptable. People demand safety in their financial systems. Equally, discussion has to move from theory or paradigms to implementation in a deeply political environment where different groups hold diverse interests, philosophies, and economic beliefs.

It would be nice to present redesign principles that are ethically and philosophically neutral, but we doubt that this is possible. The unprecedented scale of the 2008 crash was fuelled by massive expansion of credit, arguably driven by the ex ante perception that in a crash the state would have no alternative but to bail out the financial sector. Our principles imply that we can, and should, give up some short-term economic growth to purchase some lower volatility, hopefully with better growth over the long-term. This does mean, for example, that someone who might otherwise have a job or own a house will not, and there will be controversy.

We have explored one aspect of financial system redesign – after a mega-bust, maintaining a functioning financial system with minimal state subsidy. Undoubtedly there are other areas where the financial system needs to be redesigned to achieve certain purposes, e.g. pensions, mortgages, audits, ratings, risk management or financial reporting. A measure of regulation is clearly necessary to protect consumers, make markets fair and fight crime, but regulation is only one tool for managing financial markets. We would like to hear more talk of reforms to market structures, inducing competition, promoting diversity and controlling contagions.

Principles exist within a complex environment of politics, credit, and macroeconomics. If politicians encourage poor people to borrow to buy a house on the basis that house prices will always go up, then regardless of the market structure there will be a financial crash in due course. We would particularly welcome ideas on stimulating diversity, since without diversity it is not clear how any system can prevent herding, leading to correlated failures requiring state rescue.

We strongly believe that any reform process is probably flawed if it does not aim to develop a coherent design validated against agreed principles. No set of principles for financial systems design is complete or eternal. Any set of principles is just a starting set for addition, refinement and hopefully, future simplification. However, even a working set of principles should be helpful as a touchstone for financial system redesigners who need to evaluate their designs.

[An edited version of this article appeared as "Small Enough To Fail: A Systems Approach To Financial Systems Reform" Journal of Risk Finance, Volume 12, Number 5, Emerald Group Publishing, (October 2011), pages 435-444. This paper won a Highly Commended Emerald Literati Award.]

- ASHBY, W R, "Self-regulation and requisite variety." from Ashby, W R,. Introduction to Cybernetics, New York: Wiley, 1956. Reprinted in: Emery, F E (ed), Systems Thinking, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1970, pages 105-124.

- ARTHUR, Terry and BOOTH, Philip, Does Britain Need a Financial Regulator? Statutory Regulation, Private Regulation and Financial Markets Institute of Economic Affairs, 2010

- BRIAULT, Clive, “Fixing Regulation”, Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, October 2009.

- HALDANE, Andrew G, The Contribution of the Financial Sector: Miracle or Mirage?”, of speech at the Future of Finance Conference London, 14 July 2010

- HALDANE, Andrew G,“The $100 Billion Question”, Comments given at the Institute of Regulation & Risk, Hong Kong, 30 March 2010

- KAY, John, “Narrow Banking: The Reform Of Banking Regulation”, Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, 15 September 2009.

- MAINELLI, Michael, "Long Finance", Journal of Risk Finance, Volume 10, Number 2, pages 193-195, Emerald Group Publishing Limited (April 2009).

- MAINELLI, Michael and GIFFORDS, Bob,The Road To Long Finance: A Systems View Of The Credit Scrunch, Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation (July 2009)

- MCELWEE, Martin and TYRIE, Andrew, “Leviathan at Large: The New Regulator for the Financial Markets”, Centre for Policy Studies [2000]

- MORRISON, Alan D and WILHELM Jr, William J, Investment Banking: Institutions, Politics and Law, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ROTTIER, Stéphane and VÉRON, Nicolas, “Not All Financial Regulation Is Global”, Bruegel Policy Brief 2010/07, Bruegel, August 2010

- SCHUMACHER, E F, Small Is Beautiful: Economics As If People Mattered, London: Blond and Briggs, 1973.

- STRAUB, B H, ANGELL, I O, “Viewpoint: A Question of System”, Journal of Information Systems, Volume 2, Issue 2, 1992, pages 161-165.

- TAYLOR, Michael W, "Twin Peaks Revisited… A Second Chance For Regulatory Reform", Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, September 2009.

- TAYLOR, Michael W, "Peak Practice: How to reform the UK’s regulatory system - Implementing ‘Twin Peaks’”, Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, October 1996.

- TAYLOR, Michael W, "Twin Peaks": A Regulatory Structure For The New Century. A Proposal To Reform UK Financial Regulation By Splitting Systemic Concerns From Those Involving Consumer Protection”, Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, December 1995.