Sell-Side Research: Three Modest Reforms

By

Professor Michael Mainelli, Jamie Stevenson, Raj Thamotheram

Published by Finance & The Common Good/Bien Commun, Number 31-32 - II-III/2008, Observatoire de la Finance, pages 41-50.

Executive Summary

Investment banks ("sell-side") spend several $billion1 per annum globally creating equity research for investment clients ("buy-side"). Despite recent cutbacks, sell-side firms continue to provide equity research. Sell-side research should add significant value to investors’ understanding of quoted companies, and improve the quality of market information. Yet despite sizable resources and rewards unmatched in any other field of analytical research, sell-side research consistently:

- Misses most major insights or turning points in company analysis2;

- Errs persistently to Buy recommendations and uncritical stances supporting current company policies or fads3;

- Follows consensus forecasts and views;

- Prioritises client marketing over fundamental research;

- Focuses on short to medium term valuation formulae, rather than long term.

- Some of these failures can be traced to the lack of transparency in commercial relationships between sell-side and buy-side:

- Buy-side institutions are loath to make open, direct and significant payments for specified research services;

- Research ‘cover’ to defend buy-side decisions comes bundled in dealing costs;

- Masked research costs shift focus and power within investment banks towards corporate fee and proprietary trading income;

- Equity analysts are conflicted, having to provide research for clients, but also contribute to corporate and trading income.

- Eliminating ‘softing’ and ‘unbundling’ research has been a longstanding financial reform goal. Quality research should easily stand apart from corporate client and proprietary trading pressures. Yet firms offering unbundled research services remain mostly specialist boutiques. One legal and one voluntary initiative attempted to address these weaknesses:

- The Spitzer settlement in December 2002 aimed to create a level playing field in which buy-side investors accessed sell-side research transparently. Since then, research disclosures proliferate (more ‘red tape’) but fail to alter the preponderance of Buy recommendations and favourable research on each bank’s own corporate clients.

- The European Enhanced Analytics Initiative (EAI) in 2004 sought to encourage long-term, extra-financial research beyond short term financials. EAI linked 5% of participating buy-side institutions’ annual commission with a public ranking of sell-side competency. EAI attracted significant research from over a dozen bulge bracket and other leading banks, but failed to supplant the fully-bundled corporate, trading and commission packages. In 2008 EAI merged into the Principles of Responsible Investment initiative leaving unanswered questions about the future of Environmental Social & Governance (ESG)4,5 .

- Arguably only legally enforced separation of corporate, trading and broking functions (i.e. break-up of integrated investment banks) could achieve full transparency and independence in the supply of equity research. In the absence of political support for fundamental reform, the following three manageable steps might improve research quality:

- Full disclosure by sell-side and buy-side of all commission contracts;

- Compulsory publication by sell-side institutions of their recommendation balance (Buy/Hold/Sell) for (a) all covered stocks, and (b) corporate client stocks;

- Naming and shaming corporate managements who deny access to non-favourable analysts (‘analyst freeze-out’).

These are modest steps and simple. They would not eradicate the failings of sell-side research but they might encourage buy-side firms to see long term advantages in paying for independent, questioning sell-side research. If these modest proposals are too radical for regulation, one must question the sincerity of any desire to improve. If these proposals are too modest, then let’s welcome a sincere debate about transparency of fees, independence of research and the structure of financial services itself.

The strengths of sell-side research

Sell-side firms, and credit research agencies, have the potential to play a significant, positive role in enhancing the quality of equity market analysis and awareness. In theory, these agencies are a hugely efficient centralised resource, motivated to gather and to share investment relevant information. Even after recent cutbacks, sell-side analysts remain significantly better paid than those undertaking similar work in health, education, civil service, academia, politics, the media, mainstream corporate careers and even the law, accounting and consultancy.

Being associated with brokerages, sell-side researchers are motivated to be public, if not loud, about their opinions. Sell-side researchers have a large effect on market perceptions about particular stocks. One interpretation of a sell-side brokerage is that it is a research or publicity) machine with a brokerage attached. In contrast, the buy-side is motivated to keep information secret.

Theoretically, sell-side research contributes to market efficiency by aggregating divergent opinions into price setting. The sell-side provides shared learning about stock price formation that is widely available at low cost. This learning is based upon a statistical framework of quantitative income, cash flow, balance sheet and financial ratio modelling which has grown exponentially in technical sophistication over the past two decades.

Tighter rules on parity of disclosure and instant electronic data communication have eliminated the low hanging fruit of old-fashioned insider dealing. Insider benefits exploited a quarter of a century ago are now rare. Managements spin and slant to push or pull analysts in their direction, but announcements, presentations, Q&A, conference calls, and investor ‘one-on-ones’ have developed from sporadic initiatives into standardised Investor Relations (IR).

The failures of sell-side research

Bar a few outliers, vast daily e-mail and reporting efforts recycle published data and promote bland, consensus views with a bias towards Buy recommendations and uncritical views on current management policy or current management fads6 . Where critical views are expressed, they mostly follow a copycat cycle of clichéd invective ("lacking vision", "poor investor relations") for currently unfashionable companies. Investors tend to evaluate buy-side performance over benchmark periods shorter than the life of a typical fund, e.g. quarterly for a 30 year pension fund. All buy-side positions are constantly subject to second-guessing ex post. This creates a defensive culture in buy-side firms and a ready market for sell-side research recommendations which can be used to support almost any position. A preponderance of Buy recommendations fills a need to justify poor investments – "I bought Vodafone and lost a lot on that position, but it was recommended by Mega-Broker’s investment researchers". This buy-side need reinforces the internal pressure on sell-side analysts for positive recommendations to placate fee-paying corporate clients.

Investors evaluate buy-side performance in terms of fees, typically excluding brokerage costs. Therefore, the buy-side strongly prefers that all costs somehow find their way into brokerage costs, ‘softing’, with a consequent bias against ‘unbundling’. Given an emphasis on cost-control, buy-side firms reduce in-house research resource and increase their reliance on sell-side research which is circulated to them (and all other brokerage clients) ‘free’ as part of a brokerage service. Buy-side clients attempting to avoid quarterly under-performance are prone to converge around the consensus of corporate-filtered, uncritical and dealing-biased research. This convergent behaviour in turn creates and exacerbates bubbles.

Conflicts of interest within integrated investment banks

Within the investment banking system, the power hierarchy is clear – research analysts are not the top dog. Some of the top dogs (e.g. mergers & acquisitions deal makers) react badly to upset corporate clients. Sell-side analysts are disinclined to identify laggard companies – as opposed to leaders. Other top dogs (e.g. proprietary traders, sales staff) dislike efficient markets. Commitments to internal integrity, internal compliance rules, Chinese Walls or whistle blowing cannot evade the inconvenient truth that executives operating for the same ultimate paymaster (their investment bank) in the triple functions of corporate advisory, proprietary trading and equities research are not independent.

To paraphrase Jane Austen, it is a truth universally acknowledged that a banker in possession of a good corporate client (or indeed a trader in possession of a sizable long or short position) must be in want of a co-operative research analyst. Analysts in sell-side and credit research agencies are fully aware that they work in a conflicted business model, leading to self-censorship, often insidious but rarely explicit. It does not take more than the occasional analyst to be made "an example of" – i.e. who says something negative about an important client, doesn’t retract/apologise and who then is "let go" – for the message to get through to most analysts. Why value integrity over pay, integrity which the system neither recognises nor values?

Corporate management pressure on analysts

US executives secure more favourable research ratings for their companies from investment banks by bestowing professional favours on Wall Street analysts, as shown in a study carried out by Michael Clement of University of Texas and James Westphal of University of Michigan. By offering analysts favours, ranging from job recommendations to agreeing to speak to their clients, executives sharply reduced the chances of a downgrade in the aftermath of poor results or a controversial deal. The research, involving 1,800 equity analysts and hundreds of executives, suggests Wall Street’s conflicts of interest thrive despite supposedly radical regulatory reforms. Analysts’ representatives said that accepting favours such as those described in the study - which also include putting analysts in touch with executives at other companies and advising on personal matters - was unethical. However, according to the study nearly four out of six Wall Street analysts admitted receiving favours from company executives. The frequency of favours increased in line with the shortfall between the company’s earnings and market expectations - a crucial determinant of analysts’ stock ratings7.

Corporate management ‘sticks’ punish critical analysts with a reduction or even cessation in contact, information flow and response to questions8. ‘Freeze-out’ of an inconvenient analyst is one step short of the nuclear option of a formal complaint. Ironically, ‘freeze-out’ is more insidious and effective than a formal complaint that might turn a confident analyst into a valorous war hero.

Dearth of Main Street experience amongst analysts

Markets fluctuate violently around mis-readings of fundamental trends at macro and company levels. Animal spirits play their part, but deficiencies in analytical toolkits contribute to market errors of judgement and pricing. No system is foolproof against corporate misdeeds, self-deception and cover-up, yet it is arguable that a greater depth of experience and operational knowledge among professional analysts, even operating without conflicts of interest, might have improved investor awareness.

Depth of experience and operational knowledge do not feature on the tick-lists of investment bank recruiters in the 21st century. Sell-side firms attract the brightest and the best honours graduates and MBAs from the leading universities and business schools across the US, UK and Europe. Intellectual and analytical rigour are paramount and have played their part in raising technical standards of equity research since the ‘amateur’ 1980s. Yet few analysts can claim any operational or hands-on (Main Street) experience outside these narrow confines of tracking the reported and forecast financial performance of their sectors.

Focusing on excellent financial modelling at the expense of hands-on operational insight generates two negative side-effects. First, analysts remain loathe to examine non-modellable, extra-financial Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG) issues. Second, excellence in pure financial modelling and valuation is endorsed by high status survey recognition (II, Extel) and isolates analysts to queries and ideas emanating from outside the bubble of financial market numbers and gossip. Doing things differently risks being seen as unprofessional if not illegal. Building new, integrative theories of investment is only starting and component parts9 have yet to be linked coherently, despite encouraging moves by CFA Institute10 and EFFAS11 .

Flight from small cap to higher-fee large cap coverage

Naturally, investment bankers pressure sell-side researchers to justify their costs. According to Reuters Research, there was a 13 percent increase in the number of US companies that lost sell-side coverage completely between 2002 and 2004. Many quoted UK companies in the £100m to £300m market cap range struggle to attract coverage beyond one appointed broker analyst - "it is hard to justify providing research on companies that generate little trade"12 . As the senior editor of CFO.com notes: "…analysts who work for the sell-side research units of large brokers and investment banks are heading en masse for the economic shelter of large-cap companies. The reason for the exodus? Large-caps boast heavily-traded stocks — and their whopping fees — as well as the potential for profitable investment-banking business."13 Such harsh economics will be accentuated through the credit crisis.

Neglect of extra-financial and sustainability issues

ESG is unlikely to influence most companies’ three-year earnings and cash flow forecasts (i.e. the daily working tools of an equity analyst) but will drive long term performance and existence. Sell-side researchers do not generally pay attention to ESG, as the authors of a recent study of banking sector sell-side analysts conclude14 : "Corporate governance reporting (mandatory under listing rules under UK ‘comply or explain’) was usually unread because governance in UK banking was generally trusted by the analysts. Social and environmental reporting was universally considered irrelevant and incapable of influencing a financial forecast. It was rarely read by analysts and any suggestion that the environmental reporting might contain disclosure germane to the description of secondary (i.e. loan book) environmental risk was dismissed."

The neglect of ESG in mainstream sell-side research has a ‘permissive’ effect, skewing market consensus away from long term fundamentals and acting as a disincentive to contrarian behaviour. Companies, and whole sectors, can mask serious underlying problems for several years before being forced to acknowledge the impact in reported numbers. The unlucky exit of some bearish analysts during the lead up to the 2000 bursting of the dot.com bubble showed how hard it can be to sustain a contrarian stance against the herd. In order to pinpoint and "prove" over-valuation of dot.com stocks, researchers would have needed to look beyond individual companies towards the whole "new economy" and construct a model aggregating the "value per subscriber" for the sub-sector.

Only a few of the biggest buy-side firms have the ability to operate complex comparative models or conduct in-depth primary investigations comparing ESG performance of different companies. Buy-side firms rely on the sell-side to evaluate ESG performance

False signals between sell-side and corporate management

Sell-side analysts send signals back to management about equity market priorities and likely reactions. The broad perception amongst CEOs and CFOs is that mainstream analysts rarely initiate discussions of corporate responsibility or governance or environmental or safety issues, except when these are seen as posing specific and immediate threats to financials and value (e.g. the US refinery problems of BP in 2006). With buy-side analysts having only an hour with senior management, it is perhaps understandable that priorities have to be tightly set. But the top half-dozen sell-side analysts in any sector have greater access to management, extending up to two days per visit, and a week for overseas trips. Their inclination to deal with extra-financial issues en passant or not at all gives a clear, and negative, signal to corporate management about ESG.

There are several anecdotal examples of this. Michael Jensen and Robert Fuller note: "Enron in its heyday owned significant assets, made true innovations in its field and had a promising future. Its peak valuation required the company to grow extremely vigorously… To its detriment, it took up the challenge. The company expanded into areas in which it had no specific assets, expertise or experience… Had management not met Wall Street’s predictions with its own hubris, the result could have been different."15 Few CEOs are spared the pressure: "The investment community has no sense of social responsibility. And when I say ‘no’, I can’t use smaller words than that." That this was said by Chuck Prince is particularly telling.16

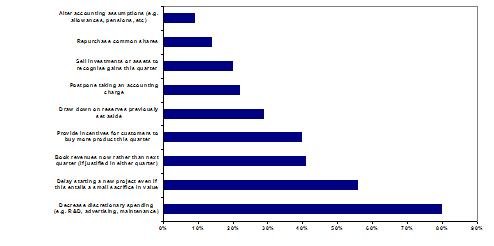

Duke University economists found CFOs had a strong propensity to trade off productive expenditure (see below) in order to "meet the number".

Figure 1: Taken from Graham, John R., Harvey, Campbell R. and Rajgopal, Shivaram, "Value Destruction and Financial Reporting Decisions" (6 September, 2006).

Two initiatives to raise research quality

Our exposure of the flaws in sell-side research is neither original nor particularly controversial. Few informed participants on either buy-side or sell-side disagree with observations about conflicts of interest and lack of transparency in the payment structure. Defenders of the existing research system argued that the global economy had enjoyed a quarter-century of unprecedented and almost uninterrupted growth in wealth and GDP from 1982 to 2007. If it ain’t broke, why fix it? The credit crunch challenges that argument, but in the absence of a material change in competition, the bulge bracket banks – with all their flaws - will continue to enjoy a brilliant concentration of analytical brainpower funded from a mix of corporate, trading and commission income.

Spitzer settlement

The Spitzer settlement in December 200217 aimed to create a level playing field in which buy-side investors accessed sell-side research transparently. But as Robert Kuttner prophetically wrote in Business Week at the time:

"Will the settlement do that? By requiring analyst compensation to be based solely on analyst performance, and by erecting a management wall between research and investment banking, the deal does make it much harder for research analysts to illegally promote stocks that their investment banker colleagues are underwriting. However, the other major element, the promise to stop spinning IPOs, is voluntary for now. An official regulatory ban awaits SEC rules.

The nub of the problem is that Wall Street and its regulators remain far too clubby. Self-regulation is delegated to the NASD, the stock exchanges, and the accounting profession, which lack the appetite to go after the conflicts that enrich their brethren. The opportunities for insiders to profit from conflicts of interest are pervasive." 18

The Spitzer settlement led to furious activity by investment banks to be seen to be strengthening their Chinese Walls. These included a series of moves to tighten up disclosure in research publications on:

- Any actual or potential corporate income interest which the bank held in any of the companies covered by the research note;

- The historic timing and performance of stocks against their recommendations;

- The balance of the firm’s stock recommendations between Buy, Hold and Sell.

Procedures are undoubtedly tighter than a decade ago, and analysts more circumspect, yet the preponderance of Buy recommendations (running at four to five times Sell recommendations) is unchanged, as is the favoured treatment of corporate stocks. Disclaimers on corporate involvement are of the lengthy, catch-all variety, which reveal little insight.

Enhanced Analytics Initiative

EAI was a voluntary initiative started in mid-2004 by European pension funds and fund managers to encourage the sell-side to invest in quality, long-term research of extra-financial issues. EAI set up two incentives for research providers to compile better and more detailed analysis of extra financial issues within mainstream research. First, a commitment to allocate 5% of broker commissions to those brokers who did good ESG work. Second, publicity for the best performers. Over a four year period, EAI grew to over twenty members and acted as the catalyst for several sell-side firms developing in-house ESG capacity.19 EAI merged in 2008 with PRI, whose much greater funds under management, about $15 trillion, expand the potential impact. Sell-side reaction to EAI showed that:

- The global reach of even bulge bracket firms is found wanting when seeking to spread against-the-grain awareness of ESG locally;

- Sell-side firms found it easier to write specialist SRI/ESG research notes for new clients than to integrate the insights into mainstream notes.

- For buy-side firms who joined EAI, it became clear that:

- It is hard to take a leadership position when the rest of the market, especially clients and investment consultants, ignore it. Whilst it may be true that "we cannot have sustainable retirement income without sustainable financial markets",20 pension executives do not have, as part of their day to day priorities, the task of looking after the long term health of the economy as a whole;

- Although firms made the commitment to join, there were questions from sell-side participants about whether the commitment translated into practice, i.e. payments.

- For buy-side firms outside EAI, it became clear that:

- The gap between funds’ espousal of long term responsible research and their giving a financial commitment to reward such research is large and widespread, leading to a chicken-and-egg argument that ESG research lacks the quality to justify taking 5% of the commission budget – which in turn deprives it of the extra funding which would help to deliver that quality;

- Fear of internal debate and tension in part explains buy-side firms’ reluctance to make formal commission allocations to specified kinds of extra-financial research, exacerbated, by the dispersal of decision-making over allocations to many individual fund managers.

Three simple proposals for modest reform

Full disclosure of research payment contracts Analysis of recommendation balance Name-and-shaming of corporate "freeze-out" tactics

- Detailed and standardised disclosure by buy-side to clients (and their agents) of financial relationships with the sell-side: Currently, the buy-side pays for research using client money. Value for money questions are serious, as stated by Integrity Research:

"the buy-side’s reliance on sell-side firms for access to company management seems to us to be rather suspect part of the value proposition of their research offering. Not only is it unclear how one can argue that management access is actually research, but it is also surprising that large buy-side firms continue to pay for a ‘concierge service’. Large buy-side firms should be able to get access to most company management teams they want to meet, thereby eliminating the need to pay so much to the sell-side to arrange these meetings."21

Moreover: "Numerous studies in recent years have shown that the value of traditional research reports has been on the wane, while other factors, including direct analyst service and management access are becoming the core source of value for the buy-side. However, the continued production of research reports by most sell-side and alternative research providers suggests that many have not understood this dramatic shift in perceived value."

Clients have a right to know how their money is spent. Hence regulators should require all buy-side firms report to their clients what goes to research/company access/trading and how it spreads across sell-side firms. In addition, the buy-side should disclose any related business arrangements with sell-side firms (e.g. stock lending, prop trading etc). As with the sell-side, associations representing buy-side should be given an opportunity to develop a standardised and appropriate framework but, if this cannot be done in due time, regulators should make clear they will define such frameworks. 2. Universal reporting framework for percentage of buy/sell/hold: One consequence of the Spitzer deal is that all sell-side firms now report, in some way, on the independence of their recommendations. At present, most brokers simply give the percentage of investment banking clients in each of the categories they monitor (generally buy, sell and hold). One way to test that research and investment banking divisions are indeed independent of each other is to see if the proportion of investment banking clients in each category is about the same. Comparison between brokers is difficult as the information is never explicitly presented and requires some calculation. What would be useful to readers of these reports would be a common reporting standard to bring some uniformity, and hence better comparability to their disclosures. Morgan Stanley comes closest to this recommendation, in that it provides the number of companies in each category for companies covered as well as investment banking clients. Morgan Stanley is the only broker to show explicitly the contrast between the buy:hold:sell numbers for all companies and those for investment banking clients. There should also be a historical track record: currently brokers provide only the latest statistics. Since this is likely not to be quick or easy for brokers to agree on an entirely voluntary basis to do what they would prefer did not happen – i.e. easy comparisons - regulators in key markets should jointly give brokers a reasonable time period in which to deliver an acceptable reporting framework, or face an imposed one .22 3. Analyst freeze-outs: One of the many things that now out-going SEC Chairman Christopher Cox indicated that his agency’s staff would look into and fully intended to ‘tackle’ was the problem of company’s freezing out analysts that wrote negatively about the company, a goal which remains unmet. As David Weild IV, a former official at Nasdaq, notes, analyst freeze-outs remain "the rule rather than the exception."23 Such freeze-outs have a negative impact on the firm’s ability to deliver access to senior management, something which the buy-side are increasingly wanting. It also reduces the analyst’s knowledge of sensitive news. Regulators should require all research firms, as a condition of their license to operate, to report companies which do this. Firms that do not report such freeze-outs should be fined. Such action would soon expose company management who take these decisions to scrutiny from board directors, media and investor scrutiny: bullying is harder in the open. In advance of such regulation, investor trade associations could play the same role but as always with voluntary whistle blowing initiatives, they will not be adequate in all countries and in all situations, so hence the need for regulatory action. What, for example, would a trade association do if it had to embarrass one of its own powerful members?

Postscript on the real purpose of regulation

Full unbundling and moving towards a world of narrow banks (perhaps resembling Glass-Steagall structures) might clear the whole "conflicts of interest" problem at a stroke. We doubt that will happen soon in the present crisis. Politicians have priorities elsewhere and are frightened of reforms that might weaken banks further. Further, unbundling and break-up of integrated investment banks would not resolve lack of transparency amongst investment funds. Only when investment funds charge their end-clients openly for the cost of advisory equity research will an open and independent market in research emerge, and so far investment funds have managed to avoid most reformatory spotlights. So we have adopted a two-pronged approach of calling in principle for fundamental reform, whilst realising that modest intermediate steps still might help. Regulation cannot change culture by itself but it can trigger governance changes within organisations and between clients and suppliers. What is needed is a ‘nudge’ approach to regulation which triggers new behaviours. For instance, promoting disclosure of comparable buy:hold:sell ratios would cause management to be interested in their relative performance on this issue and to monitor this indicator over time. As part of a balanced scorecard approach, it could lead to greater introspection and accountability than there has been to-date, not least because clients, and potentially regulators could ask outliers to explain. Given that, for example, the average buy:hold:sell ratio is about 49:39:1224, it is unclear why any house should think there are more buying opportunities than selling, and it is even more unclear why all houses should think this. Regulatory nudges must be grounded in new ways of working, including: a different, more discerning type of board director; design of compensation which places greater focus on the longer term and on risk; stronger human capital management culture25 – put simply, a greater focus on an integrated approach to sustainable financial markets.26 The ideological ‘voluntary only approach’ has been singularly ineffective in general and particularly so in terms of the market failures in investment research supply.27 So too has old style punitive regulation. Given the future role of Cass Sunstein in regulatory cost-benefit analysis in the US28, there are grounds for optimism that these three proposals could soon be put into effect, especially if asset owners and opinion-shapers make clear their support and regulators take a longer-term and systemic approach to evaluating costs and benefits and learn the lessons of regulatory capture. As the dominant paradigm is ‘better regulation’, in the absence of intensified primary regulation, i.e. markedly increased competition among the sell-side firms, we need to learn to use existing regulatory structures more effectively and quickly, and here are three proposals to get going. About the authors:

- Michael Mainelli is Director of the City of London’s leading commercial think tank, Z/Yen Group, and Professor of Commerce at Gresham College.

- Jamie Stevenson is Teaching Fellow in Finance at Exeter University and former head of research at a sell-side firm.

- Raj Thamotheram is a founder of the Enhanced Analytics Initiative and a Responsible Investment professional with experience of both asset owners and buy side. This paper has been prepared by the authors as individuals and not as representatives of any entity or organization, though all three are members of the Network For Sustainable Financial Markets - www.sustainablefinancialmarkets.net.

References

- Global investment banking revenue estimates vary between US$42bn and US$83bn. Even if only 10% is spent on equities research, this amounts to between US$4bn and US$8bn annual global research spend.

- Examples of significant missed turning points include widescale earnings manipulation in the 1980s, dotcom bubble in the 1990s, Enron and other off-balance sheet scams, BP’s safety exposure, dividend cuts in the early 1990s and now again in 2008/9, bank balance sheet failures etc.

- Are Security Analysts Fashion Victims? The Core Competence Case, Ann-Christine Schulz and Alexander Nicolai, University of Oldenburg, 2008.

- What’s The Future For ESG Broker Research, Hugh Wheelan, responsible-investor.com, 22/12/08.

- Sell side firms who closed their ESG units in 2008 include Citi, Deutsch Bank and JP Morgan.

- Are security analysts fashion victims? The Core Competence Case, Ann-Christine Schulz and Alexander Nicolai, University of Oldenburg, 2008.

- “Study reveals cosy relations between chiefs and analysts”, Financial Times, Francesco Guerrera, Ben White and David Wighton (27 July 2007).

- Immortalised in the telephone reply to former New Statesman editor John Kampfner from Tony Blair’s communications director Alistair Campbell, “Shut up and take this down, if you want any more from where this is coming from.”

- See for example, Keith Ambachtsheer work on “Integrative Investment Theory”, Andrew Lo’s work on “Adaptive Markets Hypothesis”, Woody Brock’s work on “Endogenous Risk”, Avinash Persaud on new risk thinking.

- The CFA Institute has always had a focus on personal ethics, although this personalised approach may have hindered focus on the systemic faults. CFA has broadened its focus to include corporate governance analysis and has further expanded this by considering compensation and ESG analysis: http://www.cfainstitute.org/centre/topics/governance/

- The EFFAS has set up a commission on ESG which is seeking to define key indicators and also produce a training programme: http://www.effas-esg.com/

- Fiona Buxton, Michael Mainelli, Robert Pay, Professor David Storey, Stephen Wells, “Institutional Investment And Trading In UK Smaller Quoted Companies”, The Quoted Companies Alliance, 54 pages, (October 2002)

- The Flight of the Sell-side Analyst, Marie Leone, www.cfo.com (8 July 2004).

- Analysts’ perspectives on the materiality of voluntary narratives in annual reports. Dr David Campbell, & Richard Slack, ACCA (November 2008).

- Joseph Fuller and Michael Jensen: “End the Myth-Making and Return to True Analysis,” The Financial Times (22 January 2002).

- “Business Leadership in Society”, M Blowfield & B K Googins, The Centre for Corporate Citizenship, Boston College, October 2006.

- New York State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer agreed to drop cases against major Wall Street banks for fraudulent research in return for $1.5bn fines and agreements to separate research functions more clearly from trading and corporate, and to make more transparent statements about conflicts of interest.

- Robert Kuttner, Business Week, (May 2003).

- Other key drivers have been the voting surveys like Institutional Investor and Thomson Extel (which define bonuses).

- Quote from Keith Ambachtsheer in Pension funds could show the way, Pauline Skypala, Financial Times, (4 January 2009).

- The Changing Value of Investment Research, Integrity Research, (29 July 2007).

- The precedent has been set in recent Government/Finance sector discussion in many countries. For example, according to Bloomberg, the Federal Reserve gave U.S. futures exchanges less than a week to present written plans on how they would make the $55 trillion credit swaps market less risky (28 October 2008).

- Coming Distractions, John Goff, www.cfo.com (1 April 2006).

- Unpublished analysis, Shaunak Meweda, AXA IM (2008).

- It is almost unimaginable that McKinsey reports – accurately in the authors’ experience – that banks face a talent shortage! Given the compensation packages paid, this highlights the huge weaknesses at the core of the sector’s approach to sustainable value creation: A Talent Shortage for European Banks, McKinsey & Co Quarterly, July 2008.

- www.sustainblefinancialmarkets.net

- Self-Regulation Means No Regulation, William Buiter, Financial Times (10 April 2008).

- The Sunstein Appointment: More Here Than Meets the Eye, www.progressivereform,org, (9 January 2009).

[An edited version of this article first appeared as "Sell-Side Research: Three Modest Reforms", Finance & The Common Good/Bien Commun, Number 31 – 32/2008, Observatoire de la Finance (August 2009) pages 41-50.]