Scenario Lotharios: Strategic Scenarios Of The 21st Century For The Voluntary Sector

By

Ian Harris and Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Scenario Planning 2nd edition, John Wiley & Sons (2006) pages 439-444.

The Tale of the Ancient Chinese Strategist

Once upon a time, about 400 BC in China, a man, Sun Tzu he was called, discovered strategy. Over the years, strategy as a managerial tool has settled down in its organisational place. We have begun to realise that strategy is not about the long-term rather than the short-term, but about the high-risk/high-reward decisions, rather than the day-to-day. Interestingly, the increasing acceptance of strategic planning coincides with growing academic scepticism about provable results. Objectively, we are unable to correlate performance and strategic planning, as demonstrated in one deep Z/Yen study six years ago. These troubles lead some organisations to classify planning as irrelevant or reject planning altogether. Yet at the same time, there are a lot of unprovable things in the world which we undertake in sincere belief or good faith. Much of the important work done by NGOs falls into this category.

The Story of the Over Zealous Charity Finance Director

We turn to the story of the new charity finance director who went to her first trustee meeting. Fired up with enthusiasm for her new role and full of strategic planning advice got on the cheap from an inebriated Z/Yen consultant she met at an NGO Finance drinks party, she was determined to make her mark. Her trustee presentation was filled with eyeball-popping pie charts, fantastic flip charts and detailed spreadsheets incorporating real option theory. You know the end of this story - the trustees didn't understand a word and did what they felt like doing anyway. She might as well have asked the trustees to rub a magic lamp and utter three wishes. What she needed, what we all need, is a way of making strategy and planning with numbers mean something to real people - hence the focus on scenarios, a fancy strategy word for stories.

A Stereotype is Going to Tell You a Story?

One of the biggest problems we face doing strategies and scenarios for clients is developing stories with the right spread of events to help the business. We need to be able to 'map' the universe of useful scenarios, not just make up tales. We also need to guess which story will most help which type of individual in a given situation.

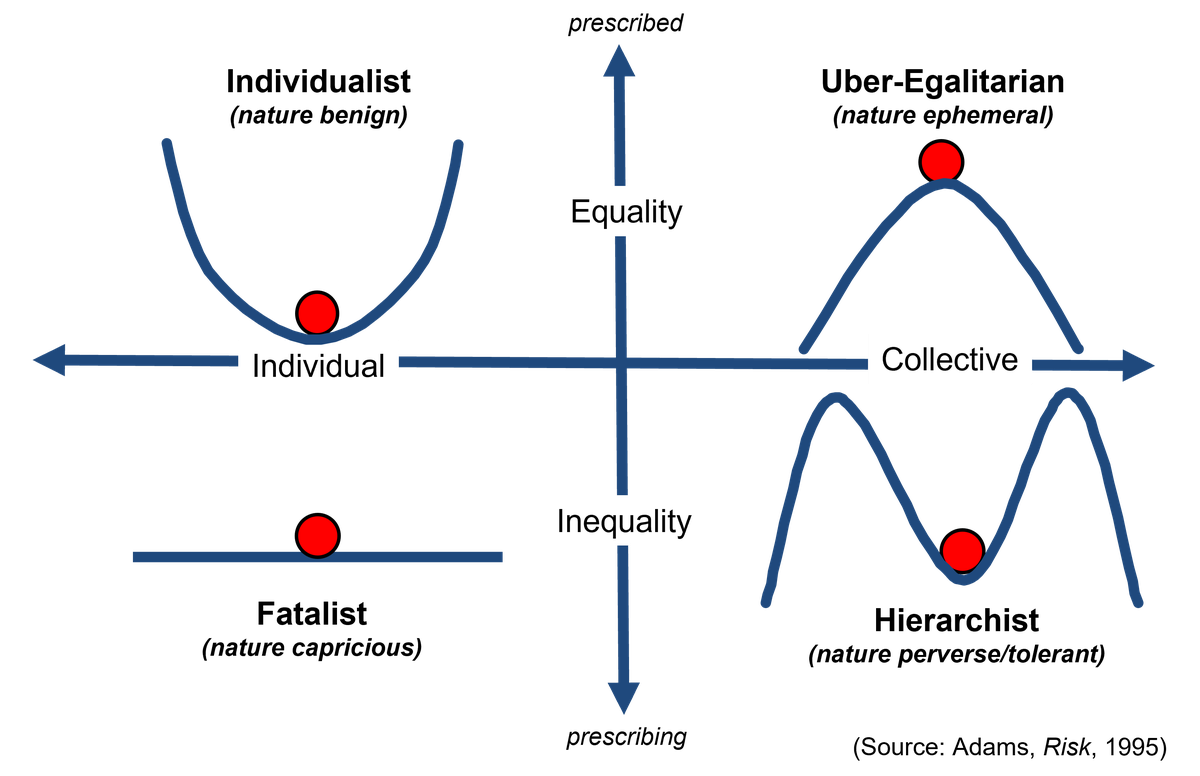

John Adams, in his work on risk structure, and others, such as Geert Hofstede's work on culture, have begun analysing perceptions of risk as ways of classifying views and cultures. Adams' first axis, the horizontal, divides people into those who look at collective risk versus those who look to themselves. His second axis, the vertical looks at those who see the world as one at the top where authority sets the rules, equally applied even if unfair, and the bottom where people make the rules themselves. The four resulting risk character types each view a different world (see diagram below).

People exhibit different risk profiles at different times and in different situations. Organisations can also have different risk profiles within different functions, e.g. accounts versus fundraising, etc. Still, let's summarise these stereotypes:

- The Individualist is almost a parody of an 80's yuppie. Nature is benign - it won't hurt him or her. At the extreme, we could put quite a few fund-raisers into this category - for the right deal a bit of tobacco sponsorship may be a good thing, after all the money was going to go somewhere.

- The Uber-egalitarian is almost a parody of a 60's or 70's socially-conscious individual - the Good Life. Nature is ephemeral, about to be overwhelmed at any minute, twenty years ago it was the coming Ice Age, today it's global warming. The uber-egalitarian mode is the working mode of many advocacy activists;

- The Hierarchist sees nature as something to be overcome, but manageable. The hierarchist is a natural bureaucrat and loves decisions based on sound thinking, however irrational the result. He or she is most likely to be the only one of the four character types who would value cost/benefit analysis;

- The Fatalist sees nature as capricious; it'll all come back and bite 'em. This position is more intriguing than it first appears. It is, after all, how most of us react to the vast majority of decisions we face every day, including things like not contesting an invalid parking ticket (you'll never win) or not changing our mortgage (they're all the same in the end).

Risk profile stereotyping is a crude tool. Individuals inhabit different positions at different times in different circumstances for different decisions. One might be a fatalist about comet disasters, an individualist about one's children's education, a hierarchist about corporate rules and an uber-egalitarian about corporate pollution.

Scenarios for the year 2020

At the CFDG conference in May, Michael Mainelli presented three possible scenarios for the sector in the year 2020, based on the Hierarchist (Power Brokers), Individualist (Free For All) and Uber-Egalitarian (Control Freaks) risk profiles. Michael left out the fatalists, but they might have known that would happen to them so why bother to complain?

In the hierarchist world of 2020, the voluntary sector has grown to 15% of GDP and exerts pressure on the IMF and the World Bank, with over £162 billion in managed funds. Expenditure limits have been agreed in many countries, but rogue organisations operate from charity havens. In the UK, fit older people are required to help with care after the passing of the National Service Act of 2010. Some pensioners are unfortunately caught by National Service both coming and going.

In the individualist 2020 scenario, the EU has closed down 50,000 rogue NGO's for illegal activities. EU activist and relief organisations have been banned in Southern Africa since they set off a small war in 2017 leading to 1800 fatalities. NGO tax exemptions have been abolished. Many NGOs now renounce all government funding. Growth has been middling.

2020 in the Uber-Egalitarian world has NGOs as the new glamour sector. UK high fliers are migrating to NGOs now that the House of Lords is powerless. AAA (Aid and Administration for Africa) now runs three African countries and has done pretty well in two of them. 20% of OECD GDP is now voluntary sector. Some say that larger charities are too cost obsessed to take risks. Special interests seem to rule.

The Legend of the Gifts from Z/Yen

The above scenarios are not gospel (or even apocrypha), they are merely thought tools. Z/Yen is happy to supply NGO Finance readers, free of charge, copies of the full text of the three scenarios, together with a page of ideas on characters, drivers, events and some provocation which may help you develop these scenarios further. Feel free to use some of the material in an informal workshop with your own organisation. Develop scenarios you believe illustrate plausible tales for you - and then use this 2020 vision to see how you could prepare today for tomorrow's uncertainties.

Skilled practitioners can wring out a bit extra, but you can get a lot on your own as long as you manage the expectations. Just remember, there is little point in any strategic planning, including scenarios, if the organisation does not genuinely wish to change. Stories can be a lot of fun. But finance people need to turn these subjective risks and rewards into numbers and plans. This is a deep subject. Suffice it to say that scenarios are an excellent way to get your senior team to give you their real views on risk and rewards. All that's left for you is to find a few tools to help you turn those views into semi-quantifiable outcomes. The tools do exist and Z/Yen would be happy to point those of you who are interested in the right directions.

The Tale of the NGO Finance Reader who Facilitated and Improved

Scenarios and story-telling can help senior management teams to generate consistency amongst perceived risks and rewards and to share a shorthand internal set of stories which encapsulate these risk and rewards in comprehensible units.

Scenarios can help organisations, including yours, to deal with the uncertainty of the future by helping to measure the unmeasurable. When you have the day job of debits and credits, SORP, VAT and other things under control, this whole world of storytelling can help you deploy new stochastic tools and techniques.

Many of you already have made the transition from critics to decision facilitators, improvers and integrators of your organisations. Some of you may be a bit apprehensive about this touchy-feely story stuff, but remember that as finance people most of you are trained in one of the few professions where the key skill is how many creative stories you can tell from just one set of numbers. So start to tell a story or two.

Control Freaks - Uber-Egalitarian

NGO’s are the new glamour sector. Since the early 00’s emergence of the MCA (Master of Charities’ Administration), the voluntary sector has been the career of choice for more and more high-fliers. The sector’s closeness to government, particularly as the second career of choice for ex-Prime Ministers given the powerlessness of the House of Lords, has led to increasing power and influence. On the international scene, the voluntary sector is the new cavalry, riding to the rescue. Since AAA (Aid and Administration for Africa) took over the management of three African countries five years ago, with at least limited success in two of the three countries, NGO’s have been the mechanism of choice for dealing with international systemic failures.

Naturally, all this activity requires resource, currently up to 20% of OECD GDP is within the voluntary sector. Much of this is tax expenditure; NGO’s working for government, implementing government policy. Charities claim that they are there to realise a better society when government and the market are unwilling or unable. Critics claim that the larger charities are too cost-obsessed to take risks. More severe critics claim that the larger charities are government lackeys, “outsourced government”, unable to say No when confronted with an unjust or unworkable policy. Some of this has been mitigated through direct participation, for instance when the Red Cross was voted out of Korea on vote4me.com, although the Charities Council always retains the right to overrule these votes.

Voluntary sector overheads are also increasing rapidly. The sector has warmly welcomed the Government Approved NGO certificate. Critics complain of the bloated policy and administration, but charities have a tremendous amount of government regulation, particularly since the £24 billion “Hug the Globe” scandal of 2007. Charities are perhaps their own best cops. In fact, most government regulation has been proposed and pushed by the voluntary sector itself. Most of the charity scams over the past ten years have been reported to the authorities by other voluntary organisations, among whom the “Angels of Malfeasance” are probably the best known. Other overheads include the new, mandatory Beneficiaries’ Councils. While perhaps a great idea at the time, these groups are frequently hijacked by special interests. A case in point is probably the diversion last year of some AIDS serum from the developing countries back to the UK because of a temporary shortage in Britain for which the Beneficiary Council insisted on taking no chances.

Looking at longer-term beneficiary relationships has led to interesting dynamics. Some countries, notably the USA, have been testing CMO’s (Charity Maintenance Organisations). In these, members are tithed on a combination of income and voluntary time. In return, members in need are guaranteed a minimum level of CMO support if they fall on hard times. What distinguishes CMO’s from other membership schemes are strong government pushes for membership (perhaps compulsory in the future), the implicit guarantee of aid for members in preference to others and the government/employer support for existing members – although critics claim that this policy of CMO annuities is merely “milk the grannies” or “beat the legacy”.

Top of page

Power Brokers - Hierarchist

The voluntary sector has grown significantly from 2000. The voluntary sector in Britain and the USA is now 15% of GDP, the result of sustained 10% real growth relative to the regular economy. European and Asian voluntary sectors are showing similar growth, albeit about a decade behind. With size has come recognition. The first meeting of the C8 in 2010 revealed that their combined annual expenditure was larger than Italy’s economy. Today, IMF and World Bank meetings honour the Observer status of the C8’s General Treasurer, while the UN Peacekeeping forces frequently report to the C8’s Commander of Voluntary Relief in non-combat situations. C8 Councils, and the new Voluntary Parliament, have struggled to inform public opinion while working with, and within, the larger international organisations. In particular, the ISO21000 standard, and its enforcement through the C8, has led to better practices and clearer delineation of the charitable sector from activists.

Growth has not been painless. Events leading up to the formation of the C8 saw the suppression of heretical voluntary organisations, acting outside the Code of Government Co-operation agreed by the major organisations within the C8. Rogue organisations, frequently based in Charity Havens, have been using the internet and other surreptitious fund-raising activities to breach the agreed 15% expenditure level agreed with the major governments. Violation of the 15% GDP expenditure level will force governments, acting to preserve a reasonable economy for their tax base, to enforce even stricter definitions of voluntary work, as France recently required a “test of total unemployability” before exempting charitable staff expenditure. Other countries may soon also outlaw volunteers because of the effect on employment statistics.

All this growth owes quite a bit to the ever-more-aggressive and successful fund raisers. By uniting globally, and with a few public “outings” of non-givers, voluntary sector giving is trendy. Making the individual 5% Norm work led to the corporate 5% Norm being successful. By structuring the funding through payrolls, the C8 Councils have been able to increase their power through ensuring control of financial resources. Responsible funders now only deal through a Funding Manager. Funding Management Organisations in the Square Mile, controlling over £162 billion, are the only authorised fund distributors in the UK. Individual donors, as always, are able to donate directly, but only a few renegade, typically larger donors do so. Renegade donors need significant sums, in one Sunday Times exposé £10 million, before they can get attention. Much of this funding structure is USA-driven. USA regulations, in particular the GOECC (US Government Organization for the Environment, Charities and Care) rulings, are increasingly forcing charities worldwide to meet US listing standards.

Beneficiaries have not been forgotten in all the growth. Increasing leisure time, combined with an aged, but too-early-pensioned retirement generation, has allowed the voluntary sector to deploy increasing numbers of workers, although demographics indicates future staffing problems. The passing of the National Service Act of 2010 was a major help to voluntary organisations, particularly as it forced older people back into helping with care. It was ironic that some pensioners were caught by National Service both coming and going.

In a series of “smash and grab” raids, southern NAFTA non-profits have been taking unauthorised liberties with the EU voluntary sector. Displacing authorised giving in areas such as humanitarian aid, cancer research and environmental relief, these NAFTA nifties are being rooted out by the Continental Revenue and the EU Border Patrol. It is testimony to the impoverished state of NGO’s globally, that unauthorised NGO’s have targeted the richer European markets for smash and grab fund-raising. Nevertheless, EU authorities have also had to shut down over 50,000 European NGO’s in the last year for illegal activities in support of their causes.

Within Europe, NGO’s spend at least as much effort fighting their European brethren. Strongly-defined battle lines exist not just in the long-running abortion versus birth-control or slavery-purchase versus child-labour conflicts, but also in the pharmaceutical-cooperative versus patent-breaking malaria and AIDS conflicts, the children’s rights versus less-than-zero-tolerance conflicts and the legalise versus criminalise drugs conflicts. The Southern African Control Zone has banned all EU activist, and most relief, organisations since the incident in 2017 when a pitched battle and bombings led to a small-scale war with over 1,800 casualties. To this day, Swiss NGO staff still have trouble getting clearance because of their military service.

NGO’s have also struggled with middling growth. While some of the headline causes remain as popular as ever, donors seem to want evidence of smaller NGO’s intention to seek their own superfluity – “we hold ourselves accountable to both those we seek to assist and those from whom we accept resources”. This has driven some NGO’s to renounce all government funding as detracting from the main mission. Changing society’s commitment to causes through activism is believed to be far more important than the direct alleviation of need. Voluntary sector groups have witnessed severe schisms between those who will, and those who will not, work with government. Perhaps the most vivid illustration of these schisms was the cancellation last year of the EUCVO because of the successful “Say No to Government” boycott.

Clearly, some of the middling growth is down to the anti-tax-break movement of 2005. In a strong bid to catch up with the USA, the EU decided to unite on at least one tax-break area; all NGO tax exemptions were abolished as too arbitrary and unfair. Despite years of legal wrangling, this abolition has held up in the European courts and has intensified over the years as consumers refuse to deal with charities that take from government – “A Charity is for Life, Not Just a Tax Break”. There has been some silver lining to the removal of special exemptions. Commercial regulations and company law requirements reduced some voluntary sector specialisms, removed some arbitrary regulators and opened the sector to probity without special laws.

The removal of exemptions has led to the removal of gloves by charities, with a more aggressive, pro-beneficiary stance. More and more voluntary sector organisations help beneficiaries coerce government, locally through consumer-style aid and information, at a national level through lobbying and legal action. Some of the US organisations are in hot water over their use of Political Action Committees (PACs) in the last election, but globally, most seem to agree that given their independently-raised funds, charities have every right to participate fully in democracy.

Top of page

Free for all - individualist

In a series of “smash and grab” raids, southern NAFTA non-profits have been taking unauthorised liberties with the EU voluntary sector. Displacing authorised giving in areas such as humanitarian aid, cancer research and environmental relief, these NAFTA nifties are being rooted out by the Continental Revenue and the EU Border Patrol. It is testimony to the impoverished state of NGO’s globally, that unauthorised NGO’s have targeted the richer European markets for smash and grab fund-raising. Nevertheless, EU authorities have also had to shut down over 50,000 European NGO’s in the last year for illegal activities in support of their causes.

Within Europe, NGO’s spend at least as much effort fighting their European brethren. Strongly-defined battle lines exist not just in the long-running abortion versus birth-control or slavery-purchase versus child-labour conflicts, but also in the pharmaceutical-cooperative versus patent-breaking malaria and AIDS conflicts, the children’s rights versus less-than-zero-tolerance conflicts and the legalise versus criminalise drugs conflicts. The Southern African Control Zone has banned all EU activist, and most relief, organisations since the incident in 2017 when a pitched battle and bombings led to a small-scale war with over 1,800 casualties. To this day, Swiss NGO staff still have trouble getting clearance because of their military service.

NGO’s have also struggled with middling growth. While some of the headline causes remain as popular as ever, donors seem to want evidence of smaller NGO’s intention to seek their own superfluity – “we hold ourselves accountable to both those we seek to assist and those from whom we accept resources”. This has driven some NGO’s to renounce all government funding as detracting from the main mission. Changing society’s commitment to causes through activism is believed to be far more important than the direct alleviation of need. Voluntary sector groups have witnessed severe schisms between those who will, and those who will not, work with government. Perhaps the most vivid illustration of these schisms was the cancellation last year of the EUCVO because of the successful “Say No to Government” boycott.

Clearly, some of the middling growth is down to the anti-tax-break movement of 2005. In a strong bid to catch up with the USA, the EU decided to unite on at least one tax-break area; all NGO tax exemptions were abolished as too arbitrary and unfair. Despite years of legal wrangling, this abolition has held up in the European courts and has intensified over the years as consumers refuse to deal with charities that take from government – “A Charity is for Life, Not Just a Tax Break”. There has been some silver lining to the removal of special exemptions. Commercial regulations and company law requirements reduced some voluntary sector specialisms, removed some arbitrary regulators and opened the sector to probity without special laws.

The removal of exemptions has led to the removal of gloves by charities, with a more aggressive, pro-beneficiary stance. More and more voluntary sector organisations help beneficiaries coerce government, locally through consumer-style aid and information, at a national level through lobbying and legal action. Some of the US organisations are in hot water over their use of Political Action Committees (PACs) in the last election, but globally, most seem to agree that given their independently-raised funds, charities have every right to participate fully in democracy.

Michael Mainelli and Ian Harris are directors of Z/Yen Limited. Z/Yen specialises in the application of risk analysis and return incentives to strategic, systems, human and organisational problems in order to improve performance. Z/Yen clients to date include blue chip companies in banking, insurance, distribution and service companies as well as many charities and other non-governmental organisations.

[Republished as "Z/Yen Scenarios for Voluntary- Sector Organisations" Gill Ringland, Scenario Planning 2nd edition, John Wiley & Sons (2006) pages 439-444.]