Organisational Enhancement: Viable Risk Management Systems (2 parts)

By

Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Kluwer Handbook of Risk Management, Issues 27 & 28, Kluwer Publishing (16 April 1999), pages 6-8.

One of the most interesting recent developments in organisational systems and governance has been the emergence of viable risk management systems (VRMSs). VRMSs are a sophisticated management tool, not a transient financial decision. Some management thinkers believe that VRMSs will be the fundamental management paradigm for the next generation of successful firms.

For risk managers, VRMSs move risk management techniques to the core of the organisation by:

- encouraging the organisation to look at all its risks, not just financial ones;

- devising appropriate mechanisms for the organisation to manage risk, including eliminating the risk, managing the effects, no-insurance, self-insurance, commercial insurance, re-insurance, captives and other pooling mechanisms;

- sharing information on risks and best practice methods of dealing with risks;

- providing comparative information on risk management for line managers;

- showing line managers the financial implications and the financial results of all risks they take which the organisation has decided need to be explicitly controlled.

VRMSs bridge a classic divide in organisations, the chasm between revenue generation and control of expenditure. This divide has many splintered fronts - sales versus finance; the risk/reward culture of performance related pay versus the stability culture of human resources; creativity and innovation versus quality control and bureaucracy. If the tension across this divide is not managed in accordance with the environment, the dissonance leads to a poorly functioning organisation. There are many dysfunctional examples - creative media firms too constrained by bean counters, banks overwhelmed by the antics of some creative financial traders, government agencies swamped by inertia or chaotic through initiative. Part of the problem is that management systems both reflect and exacerbate the divide. Management systems tend to fall strongly on either side of the divide into those of controlling risk - 'thou shalt not' - or into the side of enhancing reward - 'if you achieve, you will get'. What is missing is calculated risk in the middle - break a few branding rules to see if you can launch a new product, bypass some quality control procedures in order to satisfy a customer's expectation of delivery on time. While organisational guerrillas who break the rules make good television or film, they cause headaches for real-life organisations because when they succeed they appear to show that the System is wrong; when they fail they show that failure is against the rules. Sophisticated organisations are learning that their existing control systems are too primitive to aid these guerrillas, who are almost always working to the benefit of the firm.

VRMSs address this gap by integrating management decisions on risk and reward along lines that all managers understand - financial measurement. If a manager in a bank chooses to work with clients who are closer to going bankrupt, he or she will charge more for the money they lend than another manager who lends to `safe' clients. Returns should justify the risks. It is one thing to chastise a manager for taking a risk; it is another thing to allow him or her to take it, but with a good approximation of the cost incurred. In all organisations, financial reporting forms a common control backbone. Finance is one of the most evolved organisational functions. Some of the most intractable management problems come from organisations that have encouraged a profusion of reporting mechanisms and measurements, an environmental hazard in government organisations and NGOs. When management set too many measures, few are ever met. There are many potential measures - quality control, customer service, environmental leakages, adverse publicity, political gaffes - but the universal reporting and measurement system is financial: financial resources must be managed. In some respects, finance directors and accountants have more in common across organisations than with their own colleagues. More than most individuals, finance functionaries move between industries easily and pick up the fundamentals of a new organisation rapidly. What financial staff fail to assimilate readily are the unique organisational risks. VRMSs excel by forcing the finance function to confront the unique organisational risks.. To a large degree, the distinguishing feature of VRMSs is that they force the organisation to put a financial value on risk.

So what is a VRMS? In simple terms a VRMS is a complete risk management system distinguished by the fact that it charges managers on the risks to which they expose the organisation. A VRMS is typically run by a dedicated unit, possibly ten to thirty people in a large multi-national, although we will look at the mechanics later. A VRMS would affect a manager in a large organisation who cuts corners on a quality system by levying a notional insurance charge for corner-cutting higher than another manager who does not cut corners. The first manager's problem is to ensure that the corners he or she cuts lead to enough additional revenue to cover the risks. The second manager's problem is to show that corporate policy adherence doesn't interfere with achieving targets. The ability to show managers the financial consequences of risks they take allows managers to make more informed decisions and see the results. Before we turn to how VRMSs work in practice, let's look briefly at risk management on its own.

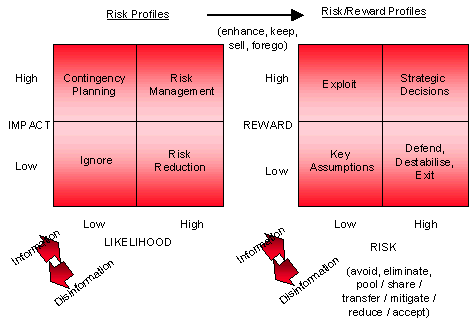

Risk management is the process of controlling risks, and the severity and likelihood of adverse events, in order to improve performance. Risk management is a popular topic and people in a variety of fields, such as banking, insurance, manufacturing, health, engineering, defence, the environment and the voluntary sector, are showing interest in how effective risk management seems to be at enhancing performance and the certainty of performance. As an introduction to risk management, two frameworks are worth considering in order to get a flavour of the field, the categorisation of risk and the mechanisms for handling risk:

Organisational risk management seems to move through four increasing levels of sophistication.

- Awareness: the basic level consists of highlighting the importance of risk management, establishing centres of knowledge, applying basic standards or accreditation, and integrating risk management with corporate ‘scorecards’;

- Engineering: at the risk engineering level, key individuals are applying risk management techniques to larger projects or issues. Engineering is typically offline, technical analysis using stochastic or simulation techniques which is then brought to the organisation’s attention through value studies or project finance decisions;

- Comparative: where risk management is a strong feature in management awareness and evaluation through personnel assessment, benchmarking or league tables;

- Systemic: where a ‘viable’ risk management system provides an internal market, external pricing and verification, dynamic re-alignment of the risk system with strategic direction and best practice sharing through peer review, databases and publications.

At the systemic, or VRMS level, the organisation moves from the primitive risk control of "thou shalt not", and away from the politically sophisticated, but ultimately corrosive "thou shalt not, but I will look away a little bit", to "thou shalt not unless for a good reason, but we will evaluate your reasons and your results over a reasonable period of time".

For example, in one aerospace organisation, each project, site and legal entity must obtain a notional insurance premium from a central risk management unit. The premium covers the manager of the entity from a list of specific financial and operational risks, permitting him or her to achieve P&L objectives within a framework of calculated risk. Most of the risks are hard (balance sheet) risks, replacing typical external insurance charges such as fire, loss of personal computers or automotive damage with an assurance from the central unit that these are covered, subject to the manager having the premium deducted from his cost centre.

The central risk management unit accepts that across a large organisation these risks are often not worth commercially insuring. Every year, the organisation will have some fires, lose some PCs and have some car accidents. The larger the corporation the more likely that common commercial insurance does not provide value-for-money for frequent occurrences. However, insurance is value-for-money at a managerial level. Why should my otherwise excellent departmental results be ruined by the loss of 20 PCs when I can insure against the loss? Managers want to ensure results where adverse events are outside their control.

Other organisational risks are softer, e.g. damage to corporate prestige or loss of organisational quality certification. The central risk management unit, if it decides to be involved, may charge all managers a premium based on their probability of adversely impacting the organisation through risks which would not normally qualify for commercial insurance easily. For instance, if the organisation is sensitive to adverse publicity, all managers may be required to pay a premium on their politically sensitive activities. For a manager who engages in politically risky projects, this premium may be significant enough for him or her to enter into negotiations with the central risk management unit on what must be done to reduce the premium - e.g. restricting the types of projects accepted, overseas locations to be avoided. In one example from a manufacturing organisation concerned about environmental breaches, all managers were required to pay a premium on their environmentally sensitive activities. The central risk management unit charged the manager of one site a hefty premium. When the manager queried this high charge, particularly after he obtained comparisons from his colleagues, he was told that the principal problem was lack of a retaining wall and a secure storage facility for hazardous gases. He was able to use the premium amount to show a two-year payback for a capital improvement that had been ignored in each previous annual expenditure round.

Managers reduce risks, often using best practice from elsewhere in the organisation, but must notify the central risk management unit of possible claims within short timescales, providing new information on near misses. The central unit publishes information (newsletters, intranets, etc.) to reduce the ‘losses’ of all its customers. This all sounds like transfer pricing and ‘playing shops’, but it has a real impact. The central unit has to put a price on the risks managers do and don’t assume - internal audit with carrots and sticks. Managers see the financial implications of many of the softer decisions they make through a unified reporting system and can show the financial benefits of longer-term projects which reduce risk, e.g. a new preventative system will reduce their notional premium.

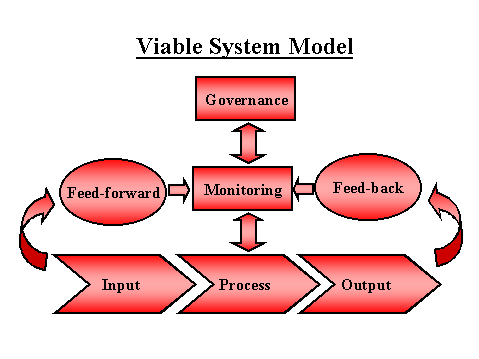

Risk management systems control risks in order to enhance performance. Viable risk management systems can be complex, with many benefits, but a summary model based on Stafford Beer's cybernetics ideas looks like this:

The following table works through seven elements of a viable systems model showing the role of a central risk management unit:

| System module | Managers | Central Risk Management Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Inputs | Training, risk assessment data, knowledge management ‘nets’, incidents | Selection, scheduling, incident alerts, near misses |

| Processes | Day to day management, peer reviews, project management | Risk assessments, premium calculations, risk/reward models |

| Outputs | Safer operating procedures, reduced process variability, fairer appraisal mechanisms | Reduced insurance premiums, better risk practices, improved performance |

| Feed-back | League tables, benchmarking, premium costs, risk databases | Financial results, perceived fairness, risk publications |

| Feed-forward | Premium reduction agreements, new behaviours | Strategic direction, corporate ‘scorecards |

| Monitoring | Operational improvements, standards accreditation | Improved management information, internal market |

| Governance | Board direction, cost of capital | External pricing mechanisms |

VRMS units often assume a number of financial functions - in fact VRMS units are most frequently located within the finance department). VRMS units take a corporate view of risks and probably purchase some spot commercial insurance, frequently re-insuring some of the most hazardous risks and even run captive insurance vehicles for the organisation, when captives make sense. It may be helpful to look at VRMSs in terms of the roles of the major players.

- Line managers. Their responsibilities include:

- day to day risk management

- longer-term planning for premium reduction

- notification of incidents. - Central risk management unit. Its responsibilities include:

- risk assessments and premium calculations

- publishing best practice information

- managing incident investigations and incident reporting

- liaising with external insurance entities

- benchmarking organisational risk exposures and management practices - Finance function. Its responsibilities include:

- measuring the central risk management unit's effectiveness

- linking the central risk management unit to internal audit practices

- unifying risk premium deductions with cost centres through the financial systems

- ensuring senior management awareness of the VRMS and its effectiveness - Specialist functions. Its responsibilities include:

- deciding when to move from basic control systems to integration with the VRMS

- assessing the overall level of corporate risk for their specialist area and inputting a value to the central risk management unit's calculations

In an era when there is much talk of devolving power, so-called tight-loose organisations, networks and even virtual organisations, there is an increasing need for sophisticated structures which harness the decisions of individual managers to the organisation's risk/reward envelope. Old style command and control systems are not up to the task of handling the more frequent and more finely-balanced decisions of today. Viable risk management systems may well evolve to be the core control systems of all future large organisations.

[A version of this article originally appeared in “Organisational Enhancement: Viable Risk Management Systems”, Kluwer Handbook of Risk Management, Issues 27 & 28, Kluwer Publishing (16 April 1999/14 May 1999) pages 6-8/6-8.]