Maximum Impact

By

Mary O'Callaghan, Professor Michael Mainelli, Ian Harris

Published by The Charity Finance Journal, (July 2004), pages 28-29.

Increasingly charities are seeking ways of assessing and maximising benefits, both for their organisation as a whole, and for activities within their organisation. As Mary O'Callaghan, Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli of Z/Yen Limited explain, portfolio analysis is an exercise that examines “more for less”, i.e., can we get more impact from fewer inputs.

Portfolio analysis can challenge established thinking, and is frequently used by managers who need to choose a combined set of “best” items. In charities, we must go beyond monetary value into less easily-measured realms of outcomes for beneficiaries or impact on society. Mary, Ian and Michael discuss portfolio analysis for charities, and outline their approach to the various issues charities are likely to encounter in making effective use of portfolio analysis.

Status Quo, Rolling Stones or T. Rex

Charities are under growing pressure to measure and maximise the impact of their work. This pressure stems from external sources (funders, regulators, the general public) and the internal desire to improve. Charities increasingly operate in a resource-constrained world. Fundraising and other forms of funding are harder to come by, costs are rising and reserves are consumed. Charities find they must try to make the most of their limited resources and work out where their money can make the most difference.

Many charities, facing the above constraints, try to rely on group consensus to make difficult decisions, often based on experience or “gut” feeling. This kind of reaction tends to discourage innovation and generally fails to challenge the status quo. Indeed, this response might be described as a “Status Quo” approach.

Some charities, facing the above constraints, curtail large swathes of activity and/or change the management team and/or latch on to any innovative idea that might lend itself to a funding proposal and/or change direction frequently in an attempt to remedy matters. This reaction tends to change so much, so rapidly that the organisation can lose focus and effectiveness, like a rolling stone that gathers no moss. Indeed, this response might be described as a “Rolling Stones” approach.

Perhaps worst of all is the oldest trick in the book for the financially constrained; salami-slicing with, for example, 5% cuts across the board each year for two years. This requires minimal thought, of course, and is in some ways equitable (if you believe that equality of pain is equitable) but this dinosaur response has a very low chance of being optimal or sensible. Indeed, this response might be described as a “T. Rex” approach.

You Can’t Always Get…….Whatever You Want

Stereotypes aside, most charities we work with struggle to separate those activities that add the most value and should be retained or expanded, from those that add less value and should be scaled down or scrapped. Charities increasingly need analytical processes that allow them to understand how they might add the most value. In charities, the definition of value normally goes far beyond monetary value into the less easily-measured realms of outcomes for beneficiaries and/or impact on society. Therefore these processes must be able to cope with the richness of charity activity, and to enable analysis of both qualitative and quantitative bottom lines.

Charities have experimented with a variety of tools like the Balanced Scorecard to measure the impact of their activities. However these tools may be unwieldy for all but the very largest charities, and often focus effort on the measurement of outputs, rather than outcomes and impact. An alternative approach which is gaining credence in the charity world is portfolio analysis. Finance people are often familiar with portfolio analysis from their investment planning and investment management work. When applied to a charity as a whole, it is basically an exercise which examines “more for less”, i.e., can we get more impact from fewer inputs. It is particularly useful in organisations that need to find a combined set of “best” services or projects, for example whether to focus resources in a variety of service types in one region, or on one type of service across many regions.

Portfolio analysis is typically initiated following a sharp reduction in income, a sudden increase in income or by concerns about the return on investment being achieved. Portfolio analysis can be quite straightforward, although you can add as much complexity as your organisation requires. A simple portfolio analysis can be carried out as a paper based exercise, while larger, more complex organisations may wish to use some statistical modelling techniques which are becoming more accessible to charities, such as Monte Carlo analysis.

We work with charities of various sizes and types; in each case, the use of tools and measurement for portfolio analysis has varied, depending on the size and complexity of the charity and its services, the amount of data available for analysis, and the participation of key decision makers in the organisation. Whatever modelling methods and tools you use, however, the real challenge will be in dividing the organisation up into sensible chunks for analysis and defining the measures you will use to understand what value, impact or “evidence of worth” your charity can and does deliver. We’ll return to these points later in the article, using a community arts centre as an example.

Tumbling Dice

While every organisation is different, we have found that six main stages are universal and the table below should prove useful regardless of size or complexity.

| Stage | Detail |

|---|---|

| 1. Establish Endeavour | Confirm the purpose, agree the components to be measured, the measures to be used and obtaining necessary data. |

| 2. Assess and Appraise | Creating the various combinations or scenarios and determining and how their impact will be measured to agree the possible scenarios |

| 3. Lookaheads and Likelihoods | Generating the combinations and prioritising those to be explored further |

| 4. Options and Outcomes | Detailed analysis of the prioritised scenarios and crossing preferred options for the organisation |

| 5. Understanding and Undertaking | Planning and implementing the transition to the preferred option |

| 6. Securing and Scoring | Ongoing management and measurement to ensure the organisation is achieving its goals |

Within portfolio analysis it is important to focus on the impact not the outputs or the process. The purpose of portfolio analysis is really to challenge established thinking, by providing a set of plausible but as yet unconsidered options to debate, better informing choices and decisions.

One of the most challenging, yet rewarding elements of the process is the exercise of putting a value on the various activities you carry out. Many charities say they have tried and failed to measure their impact, however we have found that when faced with an exercise like portfolio analysis, they can rise to the challenge. One technique is to establish a set of different types of value criteria, instead of looking to come up with a single number. For example, a charity might look at value three ways:

- beneficiary reach figures

- impact on charitable objects

- value added to information & equipment, community services, education, employment.

Another important idea is to combine a mix of hard, quantitative measures and softer qualitative judgements. Some clients feel they should not use judgements when assessing value, but they can be very useful and illuminating. For example, one charity asked its managers to score the contribution of each of the designated activities to overall customer satisfaction, excluding their own area of activity to avoid bias.

Metal Guru

Lets take a relatively simple example of a community arts centre in one location. Break the centre’s activities into discrete groups, e.g., young people’s drama, adult drama, young people’s painting, adult painting, young people’s music and adult music. These could be further divided into outreach work, and on site work. Other activities to include would be Finance and Administration, HR and Fundraising. The team needs to assess the value of each of these areas, according to agreed criteria. They also calculate current expenditure on each activity, the minimum expenditure necessary to sustain the activity and the maximum effective expenditure. These activities, expenditure levels and value scores are used to generate many potential scenarios of combinations of activities, and to put a value of each of those scenarios.

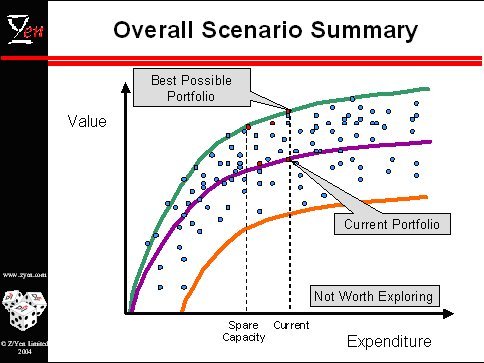

So, imagine what would happen if our arts centre dropped all adult work in the community and put those resources into community work with young people. The trick here is to examine many potential combinations of scenarios, including those that the team may never conceive of. The team might never willingly come up with a scenario that involves dropping all adult outreach work, because they may have a strong emotional commitment to it. Some of these combinations will show a loss of value, but some may show a potential gain in value (see Figure 1, the orange curve and the green curve respectively). The team selects three or four of these potentially value-adding scenarios to start their discussions about the portfolio of work and where they should invest their resources. The scenarios are only as useful as the discussions they inspire, we would be surprised if a random allocation of resources produced an ideal portfolio for your charity. However, these scenarios help charity people to think differently about the future of their organisation and spot possible ways forward they probably would not otherwise have thought about.

What You’re Proposing

How do new proposals, projects or initiatives fit into portfolio analysis? Planned new work can be included with estimates of value expected. The danger with new projects is that expectations may be more optimistic and therefore the values may be more optimistic, skewing the analysis in their favour. To avoid this happening, we recommend running different sets of analyses, one including new projects and one excluding them.

Infrastructure can be another problematic area. Charities are often tempted to exclude indirect (or overhead) costs from the analysis, as they can make individual projects or services look relatively expensive and therefore difficult to fund. However by excluding these necessary areas of expenditure you tend to get unrealistic analysis. Again, it often makes sense to run the analysis both including and excluding overheads, so you can see the impact different scenarios have on your indirect costs and do comparative cost analysis between projects or services.

Clearly any potential developments arising from portfolio analysis require further development and testing for feasibility before formal proposals for change are adopted.

Not Fade Away

In practice, the benefits achieved from portfolio analysis are to be found in the quality of the thinking it informs. Participants enjoy being presented with unexpected scenarios of activity to discuss, and find that these types of scenarios can inspire new ideas and reveal unexpected possibilities.

Ultimately the test of portfolio analysis is whether it helps the charity to make difficult decisions more easily, and improves the overall value of the charity’s work. Portfolio analysis can help you avoid simplistic, non-optimal decision making, such as “T. Rex – salami slicing”, “Status Quo – we do it because we’ve always done it” or “Rolling Stones – change everything because we want to innovate and change”. With portfolio analysis you should consider extreme and obvious scenarios, but ultimately you should find a balance that helps your charity to optimise its resource allocation decisions based on the real value of your charity’s activities.

[An edited version of this article appeared as "Maximum Impact", The Charity Finance Journal, (July 2004) pages 28-29.]

Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli are Directors and Mary O'Callaghan is a senior consultant with Z/Yen Limited, a risk/reward management practice, dedicated to helping organisations prosper by making better choices (www.zyen.com). Z/Yen clients include blue chip companies in banking, insurance, distribution and service companies as well as many charities and other non-governmental organisations.