Authors

Ian Harris, Professor Michael Mainelli and Sarah-Jane Critchley

Sponsored by

- Poptel

Published by

ICSA Publishing, ISBN:1901498123, 48 pages.

Share on social media:

You might also be interested in:

Information Technology Governance In The Not-For-Profit Sector: An ICSA Best Practice Guide

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY GOVERNANCE IN THE NOT-FOR-PROFIT SECTOR:

An ICSA Best Practice Guide

By Ian Harris, Michael Mainelli and Sarah-Jane Critchley, Z/Yen Limited

Edited by Jane Arnott and Louise Siveter, ICSA

Sponsored by Poptel

(October 2001)

© Z/Yen Limited

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Organisations in all sectors are increasingly using information technology (IT) in their work. In the not-for-profit sector, the implementation of suitable and affordable IT systems can bring considerable benefits, be it in providing a better maintained membership database or in enabling Trustees to share information more quickly. As with all new ventures, though, there are potentially costly drawbacks. Some of these may be avoidable some may not.

1.2 The purpose of this Guide is to provide help for Directors, Trustees and senior management on the effective governance of IT use within not-for-profit organisations, particularly with a view to maximising the rewards it brings while minimising risk and operating within the law.

1.3 There is a clear distinction to be made between IT governance and the use of IT in aiding governance. The former assumes a system of checks and balances that oversees the performance of IT systems in supporting the organisations’ objectives. This might include IT strategy, a policy on the staff use of IT, and performance indicators to monitor the benefits and cost-effectiveness of the technology in use. The latter concerns new opportunities and methods of working that IT may bring for Trustees, Directors and senior management. The appropriate and considered implementation of new technologies can speed up the dissemination of information, and provide improved access to critical documents. The result can be the better and smarter use of an organisation’s limited resources

1.4 The implementation and use of IT within an organisation is subject to the implications of the Data Protection Act 1998, which requires that certain conditions be met in order to ensure that personal data has been processed fairly and lawfully. The Data Protection Act applies not only to electronic data but to paper copies as well[1].

1.5 About this Guide

Throughout the Guide references are given, where appropriate, to further information and bodies who can help with any queries not addressed here. Anyone with responsibility for IT should be able to use this Guide to develop a system of IT governance from the ground up. For organisations which already have these type of systems in place, the Guide can be used to make sure that they are comprehensive. The Guide is not exhaustive, and a lot of the issues raised will not be specific to every organisation, but the intent is that what follows may help in directing organisations towards thinking about some of the wider implications of IT as a tool for operational success.

1.6 Definitions

1.7 Information Technology

Throughout this guide the term “Information Technology” or “IT” is used, to encompass technology, communications, systems, people and organisations[2]. The less familiar expressions, “ICT” (Information and Communications Technology) and “IS” (Information Systems), do not appear: their meaning is implied within the use of the broader term, “IT”.

1.8 Governance

Governance is the means by which those with ultimate responsibility for an organisation, or for responsibility with a particular function within it, direct, monitor and evaluate its work towards stated objectives, within the terms of its governing document and the relevant law. In not-for-profit organisations, this responsibility rests with the board of Directors or Trustees, who set the agenda for the organisation’s work and lay down the parameters within which this work will be carried out. The board is then responsible for monitoring and evaluating progress, and for reviewing priorities.

1.9 IT Governance

IT governance is the system that controls the access to and management of IT by an organisation. In essence, it should be fully integrated into the overall process of organisational governance. IT is just one aspect of an organisation’s affairs that requires governance. The same disciplines used to report on operational duties under corporate governance can be used to help govern IT. The overarching aim of IT governance is to ensure that its use adds value, whilst minimising and balancing risk.

1.10 Why is IT governance important to not-for-profit organisations?

IT governance is important to all types of organisations. However, the not-for-profit sector faces a number of particular challenges. One of these is the need to account to multiple stakeholders, whichmakes effective communication more difficult. The use of IT provides greater opportunities for not-for-profit organisations to communicate effectively and efficiently with a variety of audiences. The inclusive culture of the sector dictates a need for contribution, consensus, communication and commitment, and IT can be a useful tool in achieving these goals.

1.11 Not-for-profit agenciesare increasingly aware of the benefits that IT can bring, both day-to-day and long-term, and are increasingly investing in this area. However, it is important that appropriate controls are put in place to ensure that the rewards IT brings are in proportion to the sums invested in it. When public money is being spent on IT, public scrutiny will focus heavily on any undertaking that is thought to be costly or inefficient.

1.12 What are the risks?

As well as bringing fresh opportunities, IT can also expose an organisation to new risks. These may occur as a result of external factors, changes in working methods, or changes in policy direction. The key to effective risk management is knowledge: an organisation cannot decide how to approach a risk if it is unaware that it exists or is ignorant of its potential effects. It is hard to handle the unknown. This Guide identifies the most common risks that an organisation may face regarding IT, and suggests a number of ways in which those risks can be managed. Examples of model documents and material policies might address can be found in the appendix.

1.13 What are the rewards?

If IT is used and managed effectively the rewards can be substantial. There is much to be gained from achieving more at a decreased cost, making the best use of available resources, delivering core operations reliably, and exceeding expectations. Identifying the rewards that a not-for-profit organisation wants to achieve, setting targets and monitoring progress are all part of an effective system of governance.

2 STRATEGY

2.1 The activities of not-for-profit organisations are much more intrinsically tied to their prescribed objectives than is often the case in the private sector. In the case of registered charities, charitable funds can only be spent in furtherance of the charity’s purposes. When developing an IT strategy, then, the role of IT in developing these purposes should be at the core of the strategy.

2.2 A clear, comprehensive IT strategy, carefully considered and implemented, will enable an organisation to achieve its aims in a pragmatic and efficient way, and at minimum risk. For maximum ongoing benefit, this IT strategy should be reviewed as and when the organisation’s business plan is re-examined. Strategic planning for IT should be an intrinsic part of that plan, supporting the organisation’s aims rather than driving it in new – and possibly inappropriate – directions.

2.3 Defining objectives

Clearly, the strategy should aim to add value to the organisation’s functioning and service delivery, and so should relate closely to that organisation’s wider objectives. Particular aims may concern internal administration – improved management of membership information via a computerised database, for example, or financial management or an intranet for staff information – as well as the external face of the organisation. Wider possibilities include the distribution of information, support groups run via email, chat rooms or even an email counselling service.

2.4 Once the broader purposes of IT use have been agreed, these should be refined to produce a mix of short, medium and long-term goals. Short-term goals can be particularly important as they may provide the impetus to maintain commitment to the IT plan. An example of a short-term objective may be a promise to distribute all board papers via email within the next six months; a longer-term objective (over, say, two years) may be to hold virtual board meetings via the Internet.

2.5 Above all, the strategy should be realistic. All objectives should be achievable and capable of being measured against predetermined targets. The SMART model, of gains that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and with a specified Timescale, can be invaluable here.

2.6 Once objectives have been set, they must be communicated in full to the whole organisation. Keeping employees and volunteers informed will empower them to make a positive contribution.

2.7 The scope

Once an IT strategy is up and running, the range of uses to which it can be put often means it becomes the use of IT itself only increases. However, traditional methods of communication may be more appropriate in many situations, particularly when dealing with sensitive issues. It is important, therefore, that when any IT strategy is planned its limitations – that is, the areas from which it will be excluded – be just as clearly defined as those in which it will apply.

2.8 External influences

A successful IT strategy takes into account the external factors that affect the organisation. These may include government regulation, economic changes, the impact of technology and changing social values, all of which should be examined to assess their impact. This done, a risk management policy can be adopted so as to limit any undesired effects.

2.9 People and agencies obtaining services from the not-for-profit sector will affect the way that those services and information might be delivered via IT. Conversely, IT will provide opportunities for the development of different services. Young people, for example, might use the internet for information in preference to drop-in centres. Organisations might want to consider software compatibility with suppliers who may have similar needs – for example, an auditor or payroll administrator – while centralising stationery procurement, even to the extent of adopting an e-procurement system, will inevitably be more economical and more efficient.

2.10 Politicalfactors, such as changes in government policy system – the Data Protection Act 1998 is just one example – will have an impact on an organisation’s IT or on its reporting to regulators by electronic means. An integral part of IT strategy will therefore, be to ensure its use remains within the law.

2.11 The increasing ubiquity of IT in the home is opening the door to using the Internet for community work and volunteering. Any opportunities for more flexible working arrangements and home working should be considered as part of an IT strategy, supported by a clear policy for volunteers and employees.

2.12 Social factors may influence the running of an IT system. Certain types of not-for-profit organisations will need to gain access to websites that may be deemed sensitive by others, for gaining research and following current trends in their chosen field.

2.13 Internal influences

Organisations will be additionally influenced by internal stakeholders. Members, for example, may request improved access to their membership records or organisational information via email or the internet, and Trustees may find email reports a more effective way of keeping up-to-date. For larger organisations, an intranet may make it easier to co-ordinate annual leave or sickness cover. Further details of the possible benefits of an intranet can be found in the next chapter.

2.14 Internal influences will also include issues such as the size of the organisation, its sphere of influence, the level of technical expertise and resources available. An IT strategy will need to incorporate all of these, and provide a framework for development.

2.15 Managing an IT strategy

When developing the strategy, board members and senior management need to consider internal management issues, such as the following:

- What IT in the organisation is actually used for – for example, in grant-making systems or for the provision of information to stakeholders;

- The results IT in the organisation can bring – for example, the timely delivery of care or efficient processing of donations; and

- The processes needed to keep things up and running – for example, IT staff recruitment or procurement of hardware/software.

2.16 As with all strategies, the assignment of roles is important in ensuring that everyone is clear where their responsibilities lie and that every task that needs to be done is under someone’s control. Each individual should have a clear role to play.

2.17 Compatibility issues caused by changes in procurement or differing versions of software create further difficulties. Compatibility with existing systems, and the implications of any change, should always be a factor in the decision-making process. Compatibility problems can be minimised by the adoption of a staged upgrade programme, by standardising equipment – in simplest form, always using the same platform, be it PCs, Macs or whatever. This also has the benefit of smoothing out technical support and facilities sharing.

2.18 The financial resourcing of IT equipment and the training of staff and users are crucial elements in any IT strategy. The full possibilities of an IT system will not be realised unless the staff are trained to use the equipment effectively, so training is essential.

2.19 To get a complete picture of the system’s success, it is necessary to measure hard (quantitative) and soft (qualitative) performance measures. The ultimate test, of course, is the degree to which IT is helping the organisation to meet its objectives. Both quantitative and qualitative measures, applied correctly, are valuable ways of getting a picture of present success and/or failure, and can aid future long-term planning. Assuming the purpose in having an strategy on the use of IT is to define exactly what it is the organisation is trying to achieve from it, that strategy should include provision for ‘feed forward’ – i.e. processes aimed at predicting IT needs and activities (budgeting, planning and forecasting) – and for ‘feed back’, e.g. IT user satisfaction surveys or measures of performance against service level agreements.

2.20 Risk management

Having first identified the potential rewards, Trustees should ensure that IT managers should highlight and manage the potential risks that apply. Risk can either be ‘perceived’ or ‘actual’ and it is important to differentiate between the two. An individual’s experience is far more likely to reflect perceived risk than actual risk. This is partly because people rarely have access to sufficient statistical information to enable them to make a meaningful assessment of the ‘actual’ risk involved. Where empirical evidence to assess actual risk is available, it makes sense to incorporate it into a risk management policy.

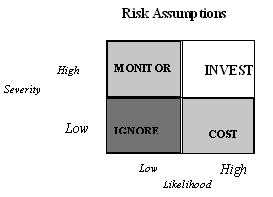

Once risks have been identified, an appropriate response should be planned, depending on the severity and likelihood of the outcome. The model below may be useful in attributing time and resources to a perceived risk and drawing up counter measures to limit its impact. For example, a risk that threatens severe effects and which is likely to happen would justify investment, whereas one that threatens little impact and is unlikely to occur might be given less attention (or could even be consciously accepted).

3 A TOOL OF GOVERNANCE

3.1 This section aims to highlight the benefits of IT systems when used as a tool of governance. The positive use of IT can facilitate increased and speedier dialogue between Trustees, staff, members and other stakeholders.

3.2 Meetings

Email use can facilitate the speedier dissemination of information between staff, Trustees, volunteers, members and stakeholders. Email, for example, offers the possibility of getting meeting notices and papers to Trustees faster.

3.3 Organisations may wish to conduct board or Trustee meetings by electronic means, provided that they can both see and hear each other and that such meetings are not expressly prohibited in the governing document.

3.4 Telephone conferencing does not constitute a valid meeting in the legal sense, although it can be a valuable forum for discussion. Where items must be decided at a meeting, it is advised that telephone conferencing not be used; that position, though, may be different if the governing document specifically provides for telephone conferencing.[3]

3.5 Intranet

An intranet is an organisation’s internal equivalent to the worldwide web, and the same software and technology used in developing a website may be used to develop an intranet. As intranets are designed for internal use they provide an ideal opportunity for increased communication across departments, separate office locations, branches, and Trustees. An intranet may be used to improve access to operational and performance-related material, such as management reports and budgets.

3.6 Internal communications could be posted onto the intranet, reducing the use of paper and promoting a more efficient use of resources. Having a copy of all-important organisational procedures on the intranet enables staff, volunteers and Trustees to have access to essential information whenever they require it. The following are just some of the more likely documents that could be made available for download on the intranet:

- Health and safety policy

- Grievance procedures

- Organisational/personnel charts

- Equal opportunities statement/anti discriminatory policies

- Codes of practice for volunteers

- Staff handbook

- Internal news

- Internal recruitment

- Expense claim forms/time sheets/requisition forms

- Budgets/performance targets

- Guidelines covering the use of IT (such as those found in Appendix 1)

3.7 One advantage to providing material via the intranet is that updates and amendments need only be made to one copy, without the need for photocopying and dissemination. This brings the added certainty that the most up-to-date version of a document is being used.

3.8 As well as providing a network for internal communication, an organisation’s intranet might also be accessible – at least in part – to external parties such as members and stakeholders. In essence the intranet is part of an organisation’s web presence, so information that is updated on the intranet is automatically linked to their official website. This may ease the maintenence of correct and relevant information available.

3.9 Intranet sites may be efficiently used as the default location for all common files. The disadvantage of this approach, though, is that the site may contain confidential information not intended for release. One possible solution could be to include a cautionary banner on the relevant pages, reminding people that the material held thereon is sensitive.

3.10 Internet

Potentially, the internet provides many advantages for the voluntary sector. It allows the dissemination of information quickly and relatively cheaply, it might be used to deliver such things such as information sheets and electronic newsletters to members, or could perhaps be used to develop a support or discussion group It may, more simply, offer information on the organisation’s aims and objectives, the services it provides, and the opinions it may have on certain issues. Annual Reports could also be provided online, enabling potential funders or users to assess the organisation’s efficiency, innovation and performance.

3.11 Websites may also be used to gather feedback from users and browsers, information that might then be used to adjust the organisation’s web presence, or act as a catalyst for a wide-ranging discussion of the issues and challenges facing the voluntary sector. Inviting comments from users could facilitate the development of better, more focussed and relevant services.

3.12 Data storage and retention

An integral part of an IT strategy is the storing of essential data and/or programmes. Ensuring that regular backup copies are kept offsite will help to reduce the risk of materials being destroyed. Organisations might want to consider the use of IT systems to facilitate the retention of official and regulatory records, which could then be maintained in a suitable format – for example, a WORM (write once read many) file[4].

3.13 Electronic banking

Electronic banking, be it over the internet or via the telephone, offers Trustees access to financial information at any time. It allows access to statements, and the power to make payments and transfer funds, as would traditional forms of banking. An added benefit, however, is that it also enables the organisation to take payments such as credit card subscriptions or donations: it will not necessarily have to use internet banking to receive electronic payments, but the payee will need access.

3.14 Electronic banking might be of additional use to those organisations that operate a branch system. It enables individual branches to have their own accounts, whilst still allowing Trustees to access information about, and to exercise overall control over, each branch’s financial activities.

3.15 Service providers may require an indemnity from the organisation or its Trustees before agreeing to provide electronic banking facilities, to cover the bank in the event of all possible losses and costs incurred as a result of the misuse of internet banking. It is recommended that Trustees think carefully about all the possible implications before giving such an indemnity[5].

3.16 Filing of accounts

It is now possible for companies limited by guarantee to file their financial returns with Company House online. This enables the speedier transfer of information and reduces the time and resources involved in compliance. The Charity Commission is currently also in the process of enabling registered charities to file accounts online (for further information contact the Charity Commission).

3.17 Grant applications

There is a growing trend for grant applications to be made online. There are a number of advantages to this process, with information accessed in the format desired, amendments made more easily and quickly, and copies made without incurring any extra cost.

3.18 Clear and comprehensive guidelines for grant applications can be accessed with relative ease, enabling an organisation to assess application criteria and compare them to its own objectives. Online information in the form of hints, tips and frequently asked questions (FAQS) might also facilitate progress by avoiding common mistakes or providing more detailed information.

4 GOVERNANCE OF IT

4.1 IT can provide many benefits for the not-for-profit sector if considered and monitored management systems are in place. Governance of IT systems applies not only to internal procedures, but affects the impact the organisation might wish to make upon the wider community. This chapter will look at possible systems for monitoring IT use and performance, and will highlight some of the legal considerations for voluntary organisations.

4.2 Measurement of IT performance

IT governance systems, once in place, should be audited regularly to ensure compliance and to ensure that the balance between risk and reward is being properly managed. The auditor should be independent – where possible a third party. It is recommended that some elements of this checking be carried out at least once a year, with particular areas scrutinised more frequently if major changes occur to the organisation, its IT or the way IT is managed.

4.3 IT systems can also be monitored against external measures such as norms, benchmarks or quality standards[6]. A set of measures can be developed to monitor system delivery – for example, the number of website ‘hits’, the number of networked users, or the number of identified faults. If the system is outsourced, a set of performance criteria should be agreed with the service provider (see below). Such measures provide reassurance that the best use and best practice principles are reflected and incorporated. Working with an established system can also save development time and cost.

4.4 There are a number of general standards in organisational governance and management that apply to all organisations, including the not-for-profit sector. Investors in People, for example, may be applicable to IT systems. There are also standards that have been developed exclusively for the not-for-profit sector, such as PQASSO (Practical Quality Assurance System for Small Organisations).[7]

4.5 The following external standards are either specific to IT or contain a dedicated IT element:

- The ISO 9000 Family of Standardsis a quality management system, which aims to enable organisations to demonstrate their commitment to customer satisfaction by preventing problems in the products or services they produce, at all stages from design to delivery.[8]

- TickITis a quality standard that applies whenever software development is carried out and the software is incorporated in the delivered product or service of the organisation applying for certification. It is a mandatory requirement of ISO 9001 and ISO 9002 certification for software development functions.[9]

- BS 7799: 1999 is aquality standard on information security management from the British Standards Institute. It includes the main standard and drawing up a specification for IT security.[10]

- BS 15000 is aimed at both providers of IT management services and organisations that have outsourced IT provision. The standard provides a set of interrelated management processes and is intended to form the basis of an audit of the managed service. It also covers relationship management.[11]

4.6 Once the relevant measures have been chosen, performance can be monitored internally or externally. Ideally, performance measures should be incorporated into a regular management cycle and handled internally. Many of the standards detailed above include a system of self-assessment, which can be combined with auditing by an external third party where appropriate. The combination of internal and external assessment offers the opportunity to develop skills within the organisation, at the same time as learning from others.

4.7 Organisationsneed to ensure that IT systems are reliable – otherwise, their implementation becomes counter-productive. Maintenance contracts can be arranged for hardware, and help desk support is normally available for software packages. Organisations may also want to implement some form of back-up procedures in the event of technical difficulties; net-based e-mail, for example, can provide an alternative email service.

4.8 Managing service providers

When external agencies are involved in managing, implementing or monitoring IT, it is essential that relationships are clear. A Service Level Agreement is an agreement between two parties that defines the responsibilities of each and the level of service both can expect. A very useful tool in the management of relationships between the IT provider and users, an SLA can help both parties to improve the level of service. A Key Performance Measurement (KPM), meanwhile, is a hard, quantitative measure of service quality. It is not a measure of the performance of any one individual – rather, it focuses on measuring the delivery of the service as the customer experiences it. For example, an SLA may read, “The supplier will arrange for support calls to be resolved within the agreed timescales’, whereas the KPM might state that, ‘95% of calls will be resolved within 48 hours’ but would only apply provided a given workload (1500 calls per month, for example) is not exceeded.

4.9 Legal issues

Although the internet is often referred to as being unregulated, there are legal requirements that relate to an organisation’s use of IT. All organisations should act within the law in the countries in which they operate. Existing law (for example, on copyright and consumer issues) relates as much to IT as it does to more traditional business concerns, and checks on legal compliance should automatically include IT.

4.10 International law

Websites are accessible to people based anywhere in the world. There are, however, a number of test cases to establish what law applies to information given online. One search engine, Yahoo, was prosecuted for allowing the sale of Nazi memorabilia through their auction sites, as the sale would be illegal in France. The EU is working to unify legislation across the Union in a number of areas, and that includes consumer rights law. The European Parliament and the Council of Europe[12] adopts a ‘country of origin’ approach, whereby the first principle is to ensure compliance with the laws of the country of origin, although this does not override existing conventions governing jurisdiction. Online terms and conditions should have a disclaimer detailing under whose jurisdiction they fall. If there are particular areas where an organisation feels it may be vulnerable on a point of international law, professional advice should be sought. If that organisation has a wide international presence, and feels particularly vulnerable, it can be a good idea to mount country-specific servers and state that any information given applies to that country only.

4.11 Data Protection Act

Organisations should be aware of their responsibilities under the Data Protection Act 1998, particularly with regard to specific provisions that relate to IT.[13] Organisations that keep personal information about people who visit their websites must be registered under the Act, and permission must be obtained to use any personal information that has been supplied. Visitors to websites need to be confident that any information they give will be used appropriately. In practice, most sites requiring personal information ask the visitor to confirm that they are willing to have their details stored; it may also be beneficial to include a privacy statement declaring the organisation’s adherence to data protection principles, and to give users online access to the information that the organisation holds on them via a user profile or account page.[14]

4.13 Declaration of status

Email can have the same legal standing as formal letters. So registered companies that do not include full company details (that is, full company name, registered office, place of registration and registered number), together with the person who authorises the communication, may be liable to a fine.[15] It is recommended that full company details be included as an email footer, along with any other disclaimer or statement of confidentiality. Registered charities with an income of £10,000 or more must declare their charitable status on financial documents such as cheques, invoices, receipts and fundraising literature. It is recommended that registered charities declare their status on all documentation, as well as on websites and email communications.[16]

4.14 E-Communications

Digital signatures became legally binding with the Electronic Communications Act of June 2000[18]. It is, however, possible to receive donations without needing to use digital signatures – via credit card, for example. There are several indications that Public Key Infrastructure (PKI), as a method of digital signature, might not offer the level of security initially envisioned. With this in mind, it might be advisable to wait until a better mechanism has been devised, or the use of PKI has been adopted by a number of household names.

4.15 Software theft

Software theft occurs when an employee downloads unlicensed software from the internet, or when the organisation has more software on its machines than it has licences for. Organisations can protect against this by ‘locking down’ desktop computers (removing systems administrator privileges from users) so that only approved people can add software onto machines owned by the organisation, and by maintaining a register of software held on each machine, together with a copy of the licence for it. This should be backed up in the organisation’s procedures manual, advising staff that it is an offence to download unapproved software. Organisations can also seek certification from the Federation Against Software Theft (FAST)[19].

4.16 Disability Discrimination Act

Under the terms of the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 it is unlawful for providers of services to discriminate against a disabled person[20] – they are instead required to take reasonable adjustments to facilitate access by people with a disability.[21] The use of IT has improved access for many people, but organisations should consider issues such as the readability of websites by people with visual impairments[22]. Sites can also be made accessible to the widest possible range of users by supplying a plain vanilla (e.g. non-graphics, no frames and no cookies) version for access by text browsers such as Lynx.[23]

4.17 Health and safety

Organisations should review their use of IT – including mobile phones – as part of their health and safety policy. A health and safety risk assessment should include a workstation check that considers issues such as lighting, VDU use, tripping hazards from cables, seating and any risk of repetitive strain injury. Health and safety training can minimise the chance of injury.

4.18 Email and internet access

Whilst access to email and the internet can be a valuable tool for many employees, to guard against inappropriate use of these tools an organisation needs to set out a statement which outlines what it defines as appropriate and inappropriate use, be it with the internet, emails or chat rooms. Abuse of email and internet access makes the organisation vulnerable to claims of harassment, defamation or discrimination and, potentially, the commission of a criminal offence by a member of staff. A sample policy on email use for staff and volunteers can be found in Appendix 2.

4.19 Technologies such as “firewalls” are available to block access to certain websites, but organisations will need to be careful in selecting which categories of site to bar. Organisations may choose to control access to a category of sites via a clearly stated policy, backed up by monitoring internet access, rather than by blocking it altogether.

4.20 Some organisations monitor staff email, phone calls and Internet use. If, though, the organisation does not make ‘reasonable efforts’ to inform staff that they are doing so, it may be liable to prosecution.[24] An email policy may provide protection to employers; a model policy is included as Appendix 2.

4.21 Security

It is recommended that all significant items of IT equipment should be recorded and listed on the organisation’s insurance schedule: the complete list should be audited at least annually. Insurance policies should include cover to allow organisations to continue to operate in the event of a catastrophic loss, in order to minimise impact on the beneficiaries. There should be a routine of daily, weekly and monthly system backups, with backup media stored offsite. A further option is offsite processing through a server farm[25] or Application Service Provider that has effective disaster recovery procedures. An example of an IT disaster recovery checklist can be found in Appendix 4. All IT equipment should be marked with a security pen for added protection against theft.

4.22 As well as the physical risks, IT systems may be vulnerable to technological damage – from a virus, for example – or external hacking into the organisation’s files. Most hacking can be avoided by the use of firewall hardware and software.[26]

4.23 Viruses, simply put, are pieces of unwanted software that have unwanted effects. They typically come via attachments to emails from outside the organisation, or on disks from an external source. Virus checking software can be installed to defend against incoming bugs and prevent the spread of viruses from the organisation’s system to that of other users. Anti-virus software should be included as an essential in any IT system.

4.24 It is advisable to place a disclaimer at the bottom of emails and web sites informing users that the organisation has taken every possible step to prevent the spread of computer viruses, but accepts no liability should a virus occur. An example of such a statement can be found in Appendix 3.

4.25 Any information obtained online needs to be collected in a safe and secure fashion, to prevent hackers gaining access to any data and using it for ends inconsistent with the organisation’s aims. Organisations should write a computer security policy to control access to, and the appropriate use of, organisational systems. A firewall can ensure the physical separation of internal and external systems.

4.26 Cyber squatting is the practice of setting up a website in another organisation’s name of, and for organisations which depend upon their good name to attract support it can be a serious problem. Checking search engines regularly will reveal if anyone else is using the organisation’s name. The problem, though, could be circumvented by the organisation registering sites under the main variations on its name, and re-routing visitors from these sites to the principal website.

4.27 ‘Spamdexing’ is where unscrupulous web designers insert hidden words into a website, words which are visible only to search engine indexes and which trick them into giving their site preferential treatment or ranking. The more times that website lists an organisation’s name invisibly, the higher up the ratings it will appear to a search engine and the more likely it is that would-be visitors be sent to the wrong site instead. Some major search engines use software to filter out spamdexing and to prevent genuine internet users being signposted to the wrong site.

4.28 Criminals can make money from the sale of an organisation’s information, whether it be details of stakeholders or intellectual capital. Organisations should identify the value of the information they hold and develop security measures to protect data.

4.29 Websites

If the information online is inaccurate, visitors accessing the site will be at best disillusioned with the organisation, and at worst may pursue legal action if they have suffered as a result. The responsibility for information published online should be vested in one place within the organisation, rather than distributed across departments. Many organisations have either a web master or a committee, which agrees the text of data before it is published and ensures consistency across the site. Either solution, effectively implemented, should allow for a range of interested parties to influence the content of the site without compromising the integrity of the message.

4.30 It is recommended that details of the web page owner should be included on web pages, together with a ‘mailto’ address, so that comments for improvement can be incorporated into the site. Websites should be tailored to low specification systems so as to enable as many people as possible to access the range of materials on offer.

4.31 Online publishing rights reflect those which apply to other forms of media. Therefore, a note on the organisation’s publication and reproduction policies should be included.

4.32 For organisations running or using chat rooms, it might be wise to think carefully about the range of views that are likely to be expressed – after all, anything libellous posted onto the site will leave the organisation liable for claims. This might be considered a relatively high risk, and mechanisms may be introduced to reduce it.

4.33 Online donations

Many people are still sceptical about the security of purchasing items or making donations over the internet and as yet there is no method for providing bona fide registration on a site. For organisations in the not-for-private sector, though, providing links to the Charity Commission on their website will allow visitors at least to check the organisation’s status for themselves (see www.charity-commission.gov.uk). Furthermore, the Which? Web Trader scheme[27] certifies that e-tailers carrying the web trader logo follow its code of practice.

4.34 Online fundraising

Online fundraising is when an organisation obtains money or support through the internet. Fundraisers can use a variety of software products, such as databases for direct marketing, statistical analysis packages and membership management packages. The internet provides an alternative method of gaining funds from a wider audience. The problem of security, though, remains.

4.35 Online recruitment

Online recruitment can include mailshots sent by email to prospective candidates; it can also extend to the use of online recruitment agencies or databases. The online recruitment agency provides a service to both the organisation and the prospective employee.

4.36 Hotlinks

Many organisations include hotlinks on their websites that allow users to quickly access other sites of interest. There is a risk of linking to an organisation which is involved with activities that are inconsistent with the values of the original organisation, or that by being linked and listed, organisations will claim a degree of approval from each other.

4.37 It is recommended that organisations develop a policy on the use of links, and that this policy be clearly stated on the site. One option is to publish a disclaimer on the website, to ensure that visitors do not assume endorsement of any linked sites or products. For example:

“The information contained on this site is the property of [organisation name]. Any comments on the content or design of the site should be sent to [mailto address]. [Organisation name] carries no responsibility for and does not endorse any information in linked pages outside the official [Organisation Name] website.”

4.38 A second option is to ensure that links are made only with sites that belong to individuals and/or organisations whose values are consistent with your own. Some organisations state that only approved links can be included on their site, and investigate possible connections for unsuitable content.

4.39 A third option would be to display a warning page each time a link out of the home site is used.

5 CONCLUSION

5.1 This guide aims to give an overview of the issues that should be considered whenusing IT systems within not-for-profit organisations. The extent to which IT solutions are adopted, and the manner in which they are governed and controlled, will be dependent upon the culture and affluence of the organisation and the nature of its services. Organisations that are not in a position to implement a comprehensive system of IT governance should focus on priority areas, in terms of both risk and opportunity. Controls in some areas are better than no controls at all.

5.2 The setting of an IT strategy is important in enabling an organisation to achieve the objectives that it sets. Consideration should be given to the connection between the IT strategy and the wider organisational strategy. A clearly developed strategy will have a positive impact on the delivery of the organisation’s work and will reduce risk.

5.3 Monitoring the impact of IT is key to ensuring value for money and the meeting of objectives, as well as laying the foundations for future developments. Regular monitoring and evaluation will provide a strong base for future IT developments.

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Sample code of IT conduct

This document outlines a suggested code for the behaviour of individuals connected to the organisation. It is particularly relevant to staff and volunteers.

1. Purpose:

The purpose of the code of conduct is to set out the behaviour expected of people connected with the organisation in their use of IT, in the course of furthering the objects of the organisation.

2. Organisational responsibilities:

- Systems will be provided to enable individuals to carry out the business of the organisation;

- Supporting policies detailing appropriate behaviours will be put in place;

- Sanctions will be taken against those who breach this code;

- The organisation will make all reasonable efforts to inform staff of any monitoring of emails and phone calls.

3. Individual responsibilities:

- To behave in a way that will do credit to the organisation;

- To maintain the standards of honesty and integrity in all business dealings;

- To behave legally;

- To use only authorised access to systems.

4. Software

- Individuals should install and use only licensed software unless developed in-house;

- The organisation will not make or condone the making of illegal copies of software;

- Individuals will not download unlicensed software from the internet;

- Individuals will seek the approval of the organisation before using freeware or shareware.

5. Violations

- Violation of this code will result in disciplinary action up to and including termination, and/or legal action if warranted;

- Employees should report any misuse of organisation systems or violations of this policy to the appropriate organisation official.

Appendix 2: Sample email policy

This document outlines suggested organisation rules and procedures and employee responsibilities for organisation electronic mail (email) messages sent or received via the organisation's email systems. It should cover both the internal and external network systems and services to which the organisation subscribes.

1. Purpose:

The purpose of organisation email is to conduct organisational business.

2. Ownership:

- Organisation email equipment and messages are and remain the organisation’s property;

- Messages that are created, sent or received using the organisation's email system are the property of the organisation;

- The organisation reserves the right to access and disclose the contents of all messages created, sent or received using its email system.

3. Usage:

- All organisation email communications must be handled in the same professional manner as a letter, fax, memo or other business communications;

- All outgoing email must contain the company details in the footer, for example:

Any Company Limited, Registered Office: Any Office, Any Street, Any Town, AN1 1NA Postcode

Registered in England, Company Number 123456789

www.anyco.com

- No copyrighted or proprietary information is to be distributed by organisation email unless approval has been granted by a organisation official;

- No commercial messages, employee solicitations, messages of a religious or political nature are to be distributed using organisation email;

- Organisation email messages may not contain content that may be considered offensive or disruptive. Offensive content includes but is not limited to obscene or harassing language or images, racial, ethnic, sexual or gender specific comments or images, or other comments or images that might offend someone on the basis of their religious or political beliefs, sexual orientation, national origin or age;

- Employees may not retrieve or read email that was not sent to them unless authorised by the organisation or by the email recipient.

4. Non-business email

According to organisational policy, one of the following statements might be included in the email policy to staff.

- Allowed

Incidental and occasional personal use of electronic mail is permitted. Such messages become the property of the organisation and are subject to the same conditions as organisation email; or - Not allowed

No personal business is to be conducted using organisation email; or - Segregated personal & business email

No personal business is to be conducted using organisation e-mail. Individuals may access personal emails using a web browser and personal online account e.g. Hotmail, Yahoo, Excite.

It may also be prudent to consider the following items for inclusion in the organisational email policy:

- Violation of the policy and its resultant disciplinary;

- Procedure for staff to report email misuse to senior members of staff;

Other email issues may include:

- Virus checking of attachments;

- Password protection;

- Archival/storage of old messages;

- Use of distribution lists;

- Restricting use of “copy all” for sending or responding to messages.

Appendix 3: Sample email disclaimer

The information contained in this email is confidential and may be subject to legal privilege. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not use, copy, distribute or disclose the email or any part of its contents or take any action in reliance on it. If you have received this email in error, please email the sender by replying to this message.

All reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure no viruses are present in this email. <Organisation> cannot accept responsibility for loss or damage arising from the use of this email or attachments and recommend that you subject these to your virus checking procedures prior to use.

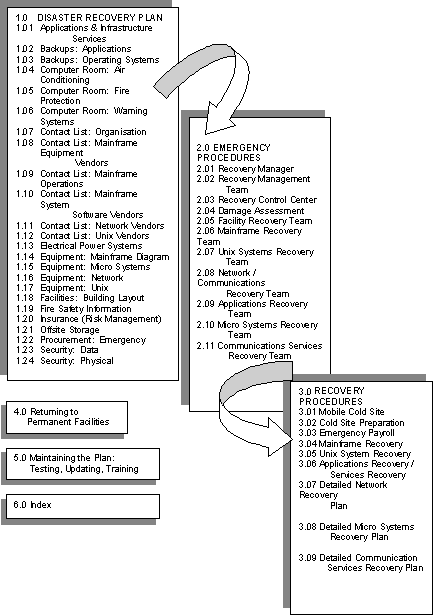

Appendix 4: Sample Disaster Recovery Checklist[28]

The checklist that follows presents an approach to disaster recovery planning by itemising the elements of the IT system to be considered in advance, suggesting emergency procedures to be carried out after a disaster, what should be included in the recovery plan and the return to permanent premises.

Appendix 5: IT Governance Checklist

The following series of questions are designed to help evaluate performance against the key areas of IT governance.

| Strategy | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Have you specified what rewards/benefits the organisation wants to achieve? | ||

| Does everyone in your organisation know what it is trying to achieve? | ||

| Have you set goals for the organisation for each of the following headings? | ||

| Do you know what IT you need to support that strategy? |

| Asset Management | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Do you know the cost of your IT? Systems? Equipment? Hardware? Software? | ||

| Do you know who owns your IT? Systems? Equipment? Hardware? Software? | ||

| Are you sharing information about the performance of your IT on a regular basis with users? | ||

| Do you know the value of IT to the organisation? | ||

| Can you confirm exactly what hardware/software you have and where it is? | ||

| Do you and your staff know who is responsible for IT? | ||

| Do you and your staff know what benefit your IT brings to the organisation? |

| Legal | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Do you know what laws you need to comply with in relation to your IT systems? | ||

| Do you comply with the Data Protection Act? | ||

| Do you comply with health and safety legislation? | ||

| Do you comply with the Disability Discrimination Act? | ||

| Do you comply with copyright law? | ||

| Do you comply with privacy legislation? |

| Organisational Survival | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Do you monitor progress against your goals? | ||

| Do you have a forward-looking planning process (feed forward)? | ||

| Do you look at what has happened in the recent past (feed back)? |

| Risk Management | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Have you identified the risks you face? | ||

| Do you have a process for identifying and managing risk? |

| Quality | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Do you have written policies for the control of your IT? | ||

| Do you your staff know what your procedures are? | ||

| Do you and your staff have IT work related instructions? | ||

| Are you assessed against any external standards? | ||

| Do you use a third party to carry out the assessment? | ||

|

Do you have specific policies for any of the following? - Code of Conduct - Acceptable Use of Computers and Telephones - Use of e-mail |

Appendix 6: Z/Yen

Z/Yen people have been working in the not-for-profit sector for a number of years and have extensive experience of the selection and implementation of IT and governance systems. Z/Yen have also been contributors to a number of other ICSA publications including The Charities Manual and, more recently Information Technology for the Not-for-Profit Sector.

Z/Yen’s mission is to be the foremost risk/reward management firm. Risk/reward management is the management of risk and enhancement of reward to strategic, systems, human and organisational problems in order to improve performance. Z/Yen believes that the intelligent management of risk is the basis of significant reward. By recognising, understanding and managing risks, more risks can be assumed and performance increased. Z/Yen applies risk/reward management in the public, private and not-for-profit sectors in areas as diverse as finance, information technology, human resources, research and development, quality, sales and marketing.

Systems of governance for IT lend themselves well to the application of risk/reward techniques, which is reflected in the use of a risk identification framework and options analysis based on a solid knowledge of the issues involved.

For more information, please explore our web site at www.zyen.com or contact Ian Harris or Michael Mainelli at the following address:

Z/Yen Limited

5-7 St Helen's Place

London

EC3A 6AU

Tel: (020) 7562-9562

Voicemail: (020) 7562-0575

Fax: (020) 7628-5751

Appendix 7: Poptel

Poptel is the UK’s leading co-operative Internet Services and Solutions Provider. With a commitment to social enterprise, Poptel has been on the forefront of the internet revolution since the very beginning. With clients mainly in the public, voluntary, ethical and membership sectors, they provide organisations with professional and innovative internet solutions and help their customers to make efficient use of these technologies.

Poptel specifically aims at enabling organisations to work for positive social change and to help them achieve their goals by using up-to-date communication technologies.

Their commitment to progressive social change is demonstrated not only through the clients they work with but also the way they run their business. They seek to support a range of ethical initiatives and thus translate the mutual nature of internet collaboration into equally co-operative new forms of social enterprise.

Appendix 8: ICSA

ICSA is the professional body for Chartered Secretaries. In addition to the professional examinations the Institute offers a range of Certificate courses, including the Certificate in Charity Management. Other initiatives in the not-for-profit sector include the Charity Secretaries Group and the Trustee Register.

The following Best Practice Guides are amongst a wider selection available from ICSA:

- Appointment and Induction of Charity Trustees

- Charities and Meetings (produced with the Charity Commission)

- Guide to Guarantee Companies

- Establishing a Whistleblowing Procedure

- Electronic Communications with Shareholders

Contact the Institute at:

Institute of Chartered Secretaries and Administrators

16 Park Crescent

London

W1B 1AH

Tel: (020) 7580-4741

Fax: (020) 7580-4741

Email: info@icsa.org.uk

ICSA Publishing Ltd

ICSA Publishing produces a range of resources including the loose-leaf manuals Company Secretarial Practiceand The Charities Manual.

Books include:

- How to Run your Charity: The Role of the Charity Secretary by Malcolm Leatherdale

- Information Technology for the Not-for-Profit Sector by Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli

Contact:

ICSA Publishing Limited

16 Park Crescent

London

W1B 1AH

Tel: (020) 7612-7043

Fax: (020) 7323-1132

Email: icsa.pub@icsa.co.uk

To order copies of ICSA Publishing Ltd books please contact:

Turpin Distribution Services Ltd

Blackhorse Road

Letchworth

Hertfordshire

SG6 1HN

Tel: 01462 488900

Fax: 01462 438011

Email: custservturpin@rsc.org

Appendix 9: Background reading

- Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli, Information Technology for the Not-for-Profit Sector. ICSA Publishing Ltd, (June 2001).

- CAF International. Non-Profit Sector in the UK. 1st Edition. CAF: Kent, page 111 – Aston Business School Three Dimensional Classification System.

- Ian Harris and Ian Theodoreson, “Who Owns Information Technology”, in The 1998 Charity Finance Yearbook, pp. 184–188.

- Edward Robinson, “Click and Cover”, in Business 2.0, pp. 126–136 (October 2000).

- Janet Gaymer, “Protect Yourself From Employee’s Online Misuse”, in Human Resources, p. 22 (September 2000).

- John Spence, “Have You Got Squatters?” in Voice, pp. 1617 (September 2000).

- Alan Stevens, “Listen Hard to Your Customers to Achieve E-Commerce Success”, in Executive Intelligence, Issue 3, pp. 4–5 (November/December 2000).

- Jon Fell, “Small Print With Big Implications: Is Your E-Commerce Solution Legal?”, in Executive Intelligence, Issue 3, pp. 1213 (November/December 2000).

- Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli “Chapter 16: Information Technology” in The Charities Manual, ICSA Publishing, London, p. 14 (2000).

- Johnathan Webdale, “DotTV expects faster take up of .tv name in Europe than US”, in New Media Age, p. 12 (14 Dec 2000).

- University of Missouri, “How to prepare and implement a Disaster Recovery Plan”

- Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, Internal Control: guidance for Directors on the combined code, Accountancy Books, London, September 1999 (Also known as the Turnbull report).

- Michael E Porter, Competitive Strategy, Free Press, New York, p. 4 (1980).

References:

- For further information on the Data Protection Act and its effect on the voluntary sector see Information Technology for the Not-for-Profit Sector by Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli, ICSA Publishing 2001. The Charity Commission website also provides operational guidance for charities on the Act.

- A full set of definitions can be found in Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli, Information Technology For the Not For Profit Sector. ICSA Publishing. (2001)

- See the Charity Commission/ICSA leaflet, CC48 Charities and Meetings

- Electronic Communications with Shareholders, an ICSA best practice guide

- Further guidance on electronic banking can be found in Guidance on Electronic Banking, from the Charity Commission. It can be downloaded on www.charity-commission.gov.uk/ccebank.htm

- Such as the Gartner Group (www.gartner,com), the Benchmarking Exchange (www.benchnet.com and www.benchmarkingreports.com)

- PQASSO is aimed at voluntary organisations of up to 20 workers and/or volunteers, or projects or units of larger voluntary organisations. It has three levels and so is scaleable to even the smallest organisations. PQASSO is available from Charities Evaluation Service, 4 Coldbath Square, London EC1R 5HL. Tel: 020 7713 5722.

- Available from the British Standards Institution, 389 Chiswick High Road, London W4 4AL. Tel: 020 8996 9000 or from www.bsi-global.com.

- Available from www.tickit.org or the British Standards Institution.

- BS 7799: 1 and 2 1999. Information Security Management. British Standards Institute, 1999. Available from www.bsi-global.com

- Also from BSI at the above address.

- Directive on Electronic Commerce (Directive 2000/31/EC), 8 June 2000

- Copies of the Data Protection Act 1998 are available from HMSO www.legislation.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980029.htm. Further information is available from the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner at www.dataprotection.gov.uk

- The OECD Privacy Policy generator can be found at http://www.oecd.org/document/39/0,3343,en_2649_34255_28863271_1_1_1_1,00.html

- Companies Act 1985, s.349

- For further information see the Charity Commission publication A Guide to the Charities Acts 1992 and 1993

- Details on the implications of distance contracts, electronic signatures, e-commerce and e-communications can be found at www.out-law.com. For updates to the law see www.bakerinfo.com/apec/ or www.venables.co.uk

- Section 7, Electronic Communications Act 2000

- Federation Against Software

- Theft (FAST) www.fast.org.uk

- Disability Discrimination Act 1995 s.19

- Section 21

- Web sites can be approved for readability by the Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) using the Web Accessibility Initiative guidelines.

- Copies of Lynx are available free from the University of Kansas www.cc.ukans.edu/about_lynx/about_lynx.html. Support files tailored for blind and visually handicapped users of Lynx, Blynx at www.leb.net/blinux/blynx explain how to number links so that they can be heard using the browser.

- Telecommunications (Lawful Business Practice)(Interception of Communications) Regulations 2000: organisations can monitor and record any type of communication without employees’ consent in order to record evidence of transactions; monitor quality and compliance; maintain operation of the computer system and detect crime or unauthorised use.

- Server Farms are a location where many computers, functioning as servers are housed.

- For a review of small-scale inexpensive firewall software, see Shields Up! at www.gr.com

- www.which.net/webtrader

- University of Virginia ITC Disaster Recovery Plan Executive Summary, www.itc.virginia.edu/security/disaster.html