Industrial Strengths: Operational Risk & Banks

By

Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Balance Sheet, Volume 10, Issue 3, MCB University Press.

Abstract: Banks are often smug about their management of risk. Smugness may well be justified for market and credit risks, but banks can learn much from industry about managing operational risk. In order to manage operational risk, industry has evolved enterprise risk/reward management systems which coordinate an internal market for risk with variations to capital charges. Industry has at least three lessons to teach banks - use activity-based costing variances to quantify operational risk; link operational risk to external prices via an enterprise risk/reward management system; and establish measures to govern an enterprise risk/reward unit.

Keywords: operational risk, banking, Basel II, activity-based costing, benchmarking, enterprise risk/reward management.

Risk, Operational Risk and Basel II

Regulators take a tough view on risk. Over the past few decades the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), based in Basel, has been working to set standards for both how risk is measured and the capital which regulators require banks to hold for the risks they take. The BIS works with the “Basel Committee on Banking Supervision” on standards for risk measurement and management. “Basel", as the shorthand goes, is used by banks to mean a variety of regulatory guidelines including those that set capital requirements based on risk. European Union regulation tends to complement Basel's guideline, e.g. the Capital Adequacy Directive. Regulators believe that capital requirements are the key regulatory mechanism for banks after supervision. "Capital is pivotal to everything that a bank does, and changing it - and we believe Basel II could change it dramatically - has wide-ranging implications for bank management and bank investors."[i] If based on risk assessments, capital requirements should change banks' behaviours toward risk because they:

- constrain a key performance measure, return on equity;

- influence a bank’s ability to lend and spend;

- limit dividends and capital repatriation.

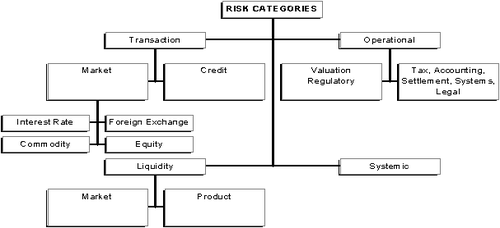

Yet risk is a difficult term to pin down. Categorising risks is more empirical than analytical and taxonomies of risk can seem arbitrary, overlapping or in contradiction with each other. For instance, the current consensus is that banks face three types of risk – market, credit and operational. Yet to an outsider, disasters such as Barings or AIB seem to be people risks, while the epidemic of US savings & loan fiascos or Argentina’s financial failures cannot be easily pigeonholed. The following diagram attempts to categorise risks, but just as easily illustrates the complexity of risk taxonomy and the potential for overlaps or multiple classifications, e.g. other diagrams separate credit and counterparty from the transaction, some ignore liquidity, etc.:

The two major Basel agreements are the Capital Accord of 1988, Basel I, and the still-in-draft-after-a-few-years Basel II. Basel I focused on market risk with some specification of credit risk. Basel I was seen to be very crude, especially for corporate lending where, despite differences in lending, say between a large multinational or a local used car dealer, all corporate lending required the same amount of capital backing. Basel I’s crudity meant that banks started to discriminate or arbitrage between regulatory and economic capital. Corporate lending markets are believed to have been starved of bank capital while low capital requirements in areas such as mortgages, asset management and insurance attracted undue banking favour. Basel I did not properly recognise credit risk mitigation and did not cover non-credit risks. Basel I had no operational risk capital requirements. Basel II's impact will be seen through three Pillars:

- Pillar 1 - Provide fixes to the minimum capital requirements of Basel I and introduce a new, specific operational risk change;

- Pillar 2 - Gives more power to the supervisor/regulator;

- Pillar 3 - insists on more disclosure to the market.

Originally planned for 2004, Basel II is running at least a couple of years late. Nevertheless, despite the lack of an official announcement, full implementation around 2006 is widely expected. During 2002 the new draft proposals are open to comment. Some regulators, e.g. the FSA in the UK, are likely to expect compliance with Basel II before the final BIS date. Most banks will be moving rapidly to full compliance during 2003 and 2004 without much push from regulators, as soon as the details are made final.

Basel II’s changes to capital requirements are felt most in Pillar 1’s extensive changes to the credit risk framework and the newly introduced operational risk requirement. Basel II has introduced a definition for operational risk as “the risk of direct or indirect loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events”. Although the BIS has admitted that this definition must be revised to exclude systemic risk more clearly, many people still see operational risk as what remains after credit risk and market risk are covered.

Larger, supposedly more sophisticated, banks are predicting that Basel II’s increased recognition of internal risk ratings by the banks themselves will free up capital. Schroder Salomon Smith Barney estimates, for instance, that Deutsche Bank can free up to €5.8 billion from market and credit risk capital under Basel II, reducing its capital requirement by 27%, from €21.6 billion to €15.8 billion. However, at €2.8 billion, operational risk would be nearly 18% of its remaining €15.8 billion capital requirement, up from nil. Operational risk capital requirements would start to matter.

Not only does God play dice, but He throws them where we cannot see them.

Stephen Hawking.

Operational Risk Management and Banks

In many respects, the Basel approach to operational risk is incomplete. At its heart, Basel permits regulators to levy an overall capital charge for operational risk. Yet successful risk management improves decision-making by linking information about risk to market prices and costs, not by imposing charges which cannot be linked to market prices or costs. As is evident from the following quote from a BBA document, banks struggle with operational risk:

“Definition. The lack of a standard definition for operational risk is the most obvious example of the lack of standardisation between firms. In essence firm specific definitions often express much the same sentiment but in local terminology. They are also a reflection of the internal solution, organisational structure and culture particular to that firm. Issues of substance also exist between firms, e.g. firms differ significantly as to whether business or strategic risk is an operational risk.

Organisational structure. Traditionally, group responsibility for operational risk has been located within internal audit. In a great number of cases this remains so today, although the approach audit has to operational risk management is now likely to be more control focused than compliance based. In contrast a growing number of firms have taken the step of establishing an independent corporate function. Increasingly this function is part of the group risk management structure on a par with market and credit risk.

Risk information. The generation of complete and consistent risk data is a primary objective for many firms. A number have reported short term gains achieved through the utilisation and comparison of existing data but an increasing number of firms are building specific operational risk identification and assessment systems. A good deal of the data is non-financial and subjective e.g. key control standards, key risk indicators, the output from operational risk self assessment. Firms also collect internal operational risk loss and near loss data. Progress is slowed by the expense of implementation and the consequent requirement to demonstrate the business value of data collection in the near term. There is a surprising degree of convergence between firms on their basic approach and the generic data requirements, divergence appears more at the level of detail.”[ii]

Basel II has not been specific about how operational risk will be calculated. Basel II currently indicates that operational risk will, on average, come to about 20% of the overall capital charge. Basel II provides three methods for calculating operational risk:

- basic indicator approach: where capital is calculated on gross income. This is a simple system but criticised for a number of reasons, not least of which is that Basel II started at 30%, most banks are assuming 20% and several analysts expect the final factor to be 10% to 15%. Setting the factor seems to be driven by regulatory politics, rather than dynamically by markets;

- standardised approach: where there is a different indicator for each line of business, e.g. corporate finance, trading, retail banking, commercial banking, payment and settlement, retail brokerage, asset management, etc. At heart, this is only a slight improvement on the basic indicator approach, merely achieving a more detailed set of indicators;

- internal measurement approach: where banks calculate their expected loss by line of business and regulators apply an additional factor. Basel has also indicated that advanced risk transfer techniques, especially insurance, will only be of benefit in lessening capital requirements for those banks which use advanced measurement techniques within the internal measurement approach.

Operational risk has many pseudo-standard sub-taxonomies, such as people (e.g. workforce disruption, fraud), process (e.g. documentation risk, settlement failure), systems (e.g. failure, security) and external risks (suppliers, disasters, infrastructure utilities failures). Yet day-to-day operational risk management involves decisions about opening times, cleaning standards, rodent control in dealing rooms, secure electricity supply, security controls and other management decisions not suitable to real-time spreadsheet analysis. There is a tension between the top-down imposition of a charge and the bottom-up nature of these detailed decisions. The following table sets out at least four levels of operational risk management:

Level Regulator Mechanisms 1.Operational risk capital requirements authorities basic indicator approach;

standardised approach;

internal measurement approach. 2. Operational risk pricing market discipline unsecured, subordinated debt issues[iii];

mutual operational risk insurance ‘clubs’, perhaps monitored by regulatory authorities;

direct insurance provision, catastrophe ‘opbonds’. 3. Operational risk norms buyer-supplier operational risk benchmark clubs;

operational risk methodologies and systems;

professional services advisors. 4. Operational risk management bank management “enterprise risk/reward management”

Level (1) does not give much guidance to an operational risk manager in a bank. The objective of most regulatory action is to minimise systemic risk. This focus preserves the banking species, but is not much help to the survival of any individual bank. Some of the long-touted mechanisms in Level (2) are starting to be taken seriously and would give some guidance to an operational risk manager, but are outside the scope of this paper. Direct insurance works if there is an informed market, a good negotiator and a lot of experience – but it supplements, not replaces, day-to-day operational risk management.

The operational risk norms in Level (3) are much-beloved by consultants and there are databases of operational losses as well as numerous ‘best practice’ guidelines. However, these databases favour large, publicly-known losses that are not of much value in daily management of operational risk. Consultants benefit from the installation of internal risk management databases, but these are biased due to small sample sizes, youth (as yet) and the lack of a management structure for operational risk in banks. There seems to be little discussion of (4) - what should banks actually do to manage operational risk? The rest of this paper attempts to show how industrial organisations manage operational risk and what banks might learn from them.

Although this may seem a paradox, all exact science is dominated by the idea of approximation.

Bertrand Russell

Operational Risk Management in Industry

The popularity of risk management in industry is due to the high impact some simple ideas and tools provide. Much of the popularity is due to the fact that, from a mathematical viewpoint, risk allows cost and flexibility to be valued. Everything - costs, variances, flexibility, complex contracts, quality measures – can be defined as a financial impact. Risk managers are found in diverse non-banking environments, e.g. manufacturers, service firms, lawyers, accountants, hospitals (clinical outcomes), charities (care outcomes), property companies. Risk managers fill diverse functional roles, e.g. health & safety, insurance risk management, project managers, business continuity or disaster planning specialists, quality managers as well as general business operations. Defining risk management is complex, even slippery. There are numerous definitions which vary in both scope and detail. For the purposes of this paper:

“Risk is the probability of an adverse occurrence multiplied by the impact of that adverse occurrence.”

“Risk management is the application of risk analysis to strategic, systems, human and organisational problems in order to improve performance. By recognising, understanding and managing risks, more risks can be assumed and performance increased.”

“Enterprise risk/reward management applies organisational knowledge to make better decisions about risk and reward through market pricing and capital charges.”

Z/Yen, in line with risk literature, discriminates among “risk” as a chance or probability, “hazard” as a danger or a dangerous object or condition, “threat” as an indication of an object or condition that could influence the level of risk. For instance, the risk of theft might have a weighted probability of £30,000; the hazard might be an unlocked door; the threat might be organised crime.

Banks do not have a monopoly on operational risk. An aircraft manufacturer runs serious operational risks from designing through building to servicing their products. An airline has operational risks from using the aircraft manufacturer’s products through sales to operations, freight and security, to name a few. What is emerging from a variety of industries is the semblance of a common approach to operational risk which this paper calls “enterprise risk/reward management”. The essence of enterprise risk/reward management is that an organisation can develop better risk management through a unit that changes behaviour through an internal risk market which shares organisational risk knowledge and through alterations to capital charges (e.g. hurdle rates).

One piece of evidence that there is an emerging industrial consensus on operational risk comes from a benchmark of risk management by Moffatt Associates among six multi-nationals beginning in 1997 – Fluor, Gillette, British Aerospace, Schlumberger, Microsoft and Northrop Grumman. Despite obvious differences in their businesses, the six attempted to compare principles and procedures, briefing and communication, risk transfer and financing. Some organisations were risk-exposure driven, some functionally risk-focused, some site driven. The rate of business change seemed to affect the type of risk management approach chosen, yet certain processes were common. Clive Moffatt of Moffatt Associates noted: “Competitive pressures and compliance (e.g. Turnbull) are forcing major companies to integrate their approaches to managing business risks.” The common processes among these and other industrial firms are increasingly managed by one entity, an enterprise risk/reward unit.

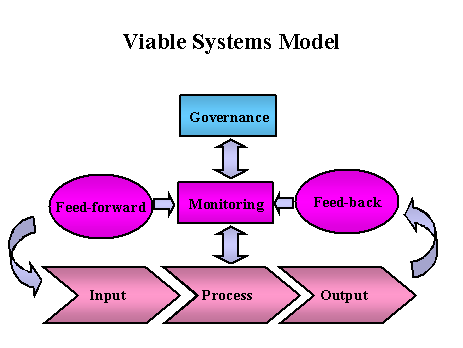

Z/Yen analyses risk/reward management in industry using the viable systems model, an approach devised by Professor Stafford Beer. The viable systems model is a key component in organisational cybernetics, the study of the design of effective social systems. The viable systems model can be summarised as saying that successful systems in complex environments have seven identifiable elements working together, viz: the implementation elements – input, process, output; the intelligence elements – feedforward, feedback; and the management elements – monitoring and governance. This can be displayed diagrammatically as follows:

Example 1 - Costing Simulation and Chemical Plant Risk

Contrasting industry approaches to operational risk with banking approaches can be illuminating. For instance, a large European chemical company wanted to reduce risk through analysis. The starting point was a project to implement a computer-based simulation tool which permitted ‘what-if’ analysis of various sequences of batches, mixes, timings, tank cleaning schedules, safety and storage procedures. The chemical company integrated the simulation tool with its financial package permitting both historic cost analysis by product, by batch, by plant or by customer and future cost analysis of planned schedules. Cost outputs were ranges showing the variance of cost. The chemical company focused on high cost variances, as opposed to high cost products, in its risk programme. Operational risk on these products was reduced, e.g. better tank cleaning sequences or better training. With reduced cost variances, the chemical company achieved lower overall costs and better safety.

Normality is a statistical illusion.

Stephen Zander

Implementation Elements - Input, Process, Output

A crucial insight regarding implementation elements is that operational risk is intimately related to quality. Quality is frequently defined as “fit for purpose”. There is a wealth of literature on quality management ranging from inspirational “rah-rah, quality is everything” approaches through qualitative ISO9000 approaches, which bear more than a passing resemblance to banks’ operational risk checklists, to semi-quantitative Six Sigma approaches which emphasise the importance of measurement. Despite the diversity of operational risk in industrial environments, one overriding principle in leading organisations is the importance of measuring variance in costs and quality.

High-risk processes tend to correlate with high cost variances. In turn, high-risk processes tend to correlate with low quality outputs. In quality-obsessive industries, constant measurement of cost variances is used to detect quality problems. Operating under the assumption that the financial systems must trap all process costs and relate them to outputs, industry uses these measures to manage operational risk. Activity-based costing systems are essential to quality measurement. Industry attempts to include the full process cost, i.e. not just direct costs such as raw materials but also rework, wastage, scrap, disputes, returns, environmental fines, etc. In many cases, industrial companies undertake discrete (most manufacturing environments) or continuous (most chemical and fluid environments) simulation modeling and then relate the models to costs.

Lesson 1 - Use Activity-Based Costing Variances To Quantify Operational Risk

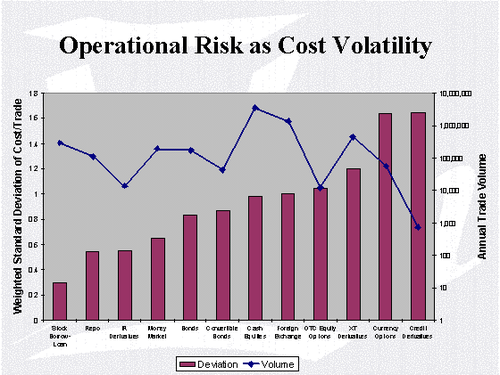

Banks have a long way to go in understanding costs. Z/Yen conducts market-wide cost comparison studies among over 25 banks annually. Many participant banks have difficulty assembling “per transaction” costs. Banks that regularly report “per transaction” costs tend to have built activity-based costing systems. From existing cost comparison studies, Z/Yen has produced charts such as the following to examine inter-bank operational risk as cost volatility:

From the chart, it can be seen that currency options, credit derivatives and exchange-traded derivatives (on the right), show greater cost variance than stock borrowing, repos or interest rate derivatives (on the left). In industry, assuming that the activity-based costing system is capturing most costs (e.g. failed trades, legal costs), the products on the right would have greater operational risk than those on the left. Despite the ubiquity of this cost variance approach in industry, it is rare to find intra-bank product comparisons used to ascertain operational risk in banking. Only a few banks, for instance one with a London-based fixed income trading floor of 500 and another with an overseas equity floor of 150, have developed simulation models which integrate with their activity-based costing systems.

A good first step for a bank looking to manage operational risk would be to develop “full” per transaction costings and examine the variances among them by product line. A good second step would be to incorporate simulation modeling to allow ‘what if’ analysis. As an aside, risk/reward option theory can be used to ‘price’ both the cost of operational risk and the benefits of options for change using similar skills to those used on the trading floor, e.g. Black-Scholes calculations.

Example 2 - Enterprise Risk/Reward Unit in Aerospace

In one aerospace organisation, each project, site and legal entity must obtain a notional insurance premium from the enterprise risk/reward unit, which is part of the finance department. The enterprise risk/reward unit charges all managers a premium based on the probability of their adversely impacting the organisation. The premium covers the manager of the entity from a list of specific operational risks, permitting him or her to achieve P&L objectives within a framework of calculated risk. In return the manager must comply with typical insurance policy requirements, submit to rigorous early incident reporting and share his or her risk data. Most of the risks are hard (balance sheet) risks, replacing typical external insurance such as fire, loss of personal computers or automotive damage with an assurance from the central unit that these are covered, subject to the manager having the premium deducted from his cost centre.

The enterprise risk/reward unit accepts that for a large organisation some risks are not worth commercially insuring. Every year, the organisation will have some fires, lose some PCs and damage some cars. The larger the corporation, the more likely that common commercial insurance does not provide value-for-money for frequent occurrences. However, insurance is value-for-money at a managerial level. Why should my otherwise excellent departmental results be ruined by the loss of 20 PCs when I can insure against the loss? Managers want to ensure results where adverse events are outside their control and will accept the charges where they are seen to be appropriate and ‘fair’. The ability to show managers the financial consequences of risks allows managers to make more informed decisions and see the results as premia rise or fall. Sharing information among managers about premia charges, near misses and claims builds knowledge. This sharing of knowledge contrasts with a typical external insurance relationship where both parties suppress information in order to preserve the bargaining power they gain through asymmetric knowledge.

‘Soft’ risks can also be managed. For instance, in an organisation sensitive to adverse publicity, all managers may be required to pay a premium on their politically sensitive activities. For a manager who engages in politically risky projects, this premium may be significant enough for him or her to enter into negotiations with the enterprise risk/reward unit on what must be done to reduce the premium, e.g. restricting the types of projects accepted, overseas locations to be avoided. Premia can also stimulate appropriate investment beyond the financial year. All managers are required to pay a premium on their environmentally sensitive activities. In one case, the enterprise risk/reward unit charged the manager of an aircraft manufacturing site a hefty premium. When the manager queried this high charge, particularly after he obtained comparisons about his colleagues, he was told that the principal problem was lack of a retaining wall and a secure storage facility for hazardous gases. He was able to use agreed premium reductions to show a two-year payback for a capital improvement that had been ignored in previous annual expenditure rounds.

He uses statistics as a drunken man uses lamp posts - for support rather than illumination.

Andrew Lang

Intelligence Elements - Feed-forward, Feed-back

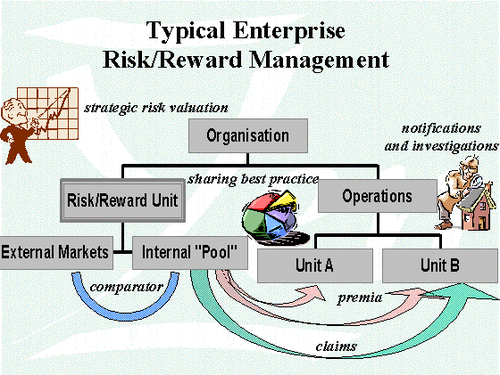

Feed-forward is about setting targets and objectives, risk-based planning or event horizon scanning. Feed-back typically measures outcomes, effectiveness, reductions in the cost of risk, risk awareness in the organisation or event and impact comparisons. Leading industrial players have evolved some highly sophisticated management approaches to ensure feed-forward and feed-back on risk, for which this paper’s generic term is “enterprise risk/reward units” – although there are many variations on the units’ functions, scope and name, e.g. risk management, quality & risk, risk transfer, insurance, even part of internal audit. In some of the largest multinationals these units deploy from 15 to 50 people. Industry has moved risk management techniques to the core of the organisation through:

- strategic risk valuation: encouraging the organisation to look at all its risks, not just financial ones, as well as devising appropriate mechanisms to manage risk, including eliminating the risk, managing the effects, no-insurance, self-insurance, commercial insurance, re-insurance, captives and other pooling mechanisms;

- internal “premia” and “claims” management: showing line managers the financial implications and the financial results of risks that the organisation has decided need to be explicitly controlled, as well as developing an internal market for risk which enforces best practices through partial indemnification;

- notifications and investigations: actively reporting and investigating near misses and incidents to learn on behalf of the organisation and using those reports to adjust the internal financial mechanisms;

- sharing best practice: using information on risks gained from notifications and investigations, from external sources and from best practice sources, to provide databases, reports, comparisons and measures which permit line managers to learn from each other;

- external comparators: providing comparative information on risk management from links with external markets, e.g. reinsurers, bond rates, benchmarking databases.

Lesson 2 - Link Operational Risk To External Prices via Enterprise Risk/Reward Units

Feed-forward is probably the area where banks best measure up against industry. Numerous reports are written, risks discussed, databases built, conferences attended. However, without feed-back, feed-forward is of limited use. The following diagram oversimplifies things, but illustrates the links between the internal market ‘pool’ and the external market:

In some ways, banks should find it easier to change behaviour through enterprise risk/reward units because existing internal capital allocation and credit committee activities can be used to adjust capital charges, affecting risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC) measures. Premia charges to managers will affect their units’ bottom line profits. As the enterprise risk/reward unit influences bonuses through capital charges and premia, behavioural change should be rapid indeed.

Example 3 - Evolutionary Risk/Reward in a Global Manufacturer

Stage 1 - Cost Centre. One global manufacturer began to approach risk by setting up a “risk audit” within the finance department. This unit had some early, easy success in its negotiations with insurers. It then developed self-insurance, setting up captive insurance vehicles that it used to negotiate better rates with re-insurers. However, the cost center was a corporate overhead which attracted a lot of political attention. Its size had been set arbitrarily and many divisions continued to pursue their own risk management and insurance programmes.

Stage 2 - Consultancy. Acceding to criticism of the cost centre, top management turned the risk unit into a “risk advisory unit” run as a profit centre. Risk analysis projects were costed as if done by an outside consultancy firm and partially subsidised. The benefit of this arrangement was that some divisions were able to learn how other divisions successfully managed risk. The consultancy unit successfully spread best practice knowledge. While this arrangement did clarify expenditure and give some simple measures on activity, e.g. utilisation, divisions felt compelled to buy and questioned the “internal market” rates. Further, consultancy was not a core organisational competence. External consultants achieved better customer satisfaction, sometimes despite less technical competence.

Stage 3 - Capital Charges. Nevertheless, top management were pleased with the success of their focus on risk. In a further reorganisation, the unit linked up with the strategy team in setting capital charges as a “risk management unit”. The unit kept its management of links with the external risk markets through its control of insurance and the captive vehicles. The unit was principally involved in helping manage risk on large or complex projects. The unit’s performance was measured on a portfolio sampling of projects and their relative success rates with, and without, the risk management unit’s involvement. The unit size was kept low and their specialist expertise was admired, but suspicions were voiced that there was self-selection of flattering projects and selective interpretation of “savings”. The unit was seen as too ‘political’, helping pet projects get low capital charges and not involved enough in day-to-day risk management practices.

Stage 4 - Enterprise Risk/Reward. Top management required the unit to get involved in day-to-day operations by running an internal market in risk, while continuing to set capital charges and manage insurances. The board set broad parameters for risk, e.g. a political incident would decrease brand value by X or loss of ISO9000 compliance would affect government sales by Y. It was up to the “risk/reward management unit” to ‘price’ these risks into premia which would alter behaviour. The unit continues to help key projects and units avoid major pitfalls by spreading best practice, but also has responsibility for reducing the organisation’s total risk exposure and increasing shareholder value. The unit is measured in several ways, e.g. reduction in premia variance, internal market alignment with external risk markets and customer satisfaction.

There's no sense in being precise when you don't even know what you're talking about.

John von Neumann

Management Elements - Governance, Monitoring

Monitoring includes target and objective setting, structures assessing payback, communications and briefings, while governance covers the risk strategy setting process, organisational inclusiveness in decisions, seniority of governance, independent reporting route(s) to the board and policy setting. An enterprise risk/reward unit can be seen to be a mirror image of a strategy implementation unit – strategy pushes the organisation forward, while the risk/reward unit ensures it doesn’t unwittingly expose itself to risks which haven’t been properly evaluated. To use a metaphor, strategy pushes you along a chosen path; risk/reward stops things pushing you off.

During the 1990’s and into the 2000’s, people paid more attention to organisational governance. In the UK a series of reports, largely directed at large, listed companies, has set out a reasonable governance framework which many organisations take as a starting point. These reports include the 1992 Cadbury Report, the 1995 Greenbury Report, the 1998 Hampel Report and the 1999 Turnbull Report. The Turnbull Report was one of the first reports to require a board to take specific account of risks and control systems for risks:

“(Board) policies should take account of the risks faced by the company, its risk appetite, the controllability of the risks and the cost/benefit of the controls identified. The control system should be embedded and responsive, it should include procedures for reporting failures and weaknesses, together with the corrective action taken.”

Guidance on corporate governance is not confined to the UK, for instance the German government has recommended a package of changes for the reform of corporate governance. KonTraG (Gesetz zur Kontrolle und Transparenz im Unternehmensbereich) came into force in 2002 as part of the law on control and transparency in business. KonTraG covers five areas, the board (risk management - boards of public limited companies are obliged to ensure that adequate risk management and internal revision systems exist in their own companies), supervisory board, shareholder rights, banks as stakeholders and the audit. Internationally, in May 1999 ministers representing the 29 governments which comprise the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) voted unanimously to endorse the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. The principles are likely to act as signposts for activity in this area by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the United Nations and other international organisations.

Lesson 3 - Establish Measures to Govern Enterprise Risk/Reward

There is little guidance on how an enterprise risk/reward unit should be governed. Industry tends to give control of these units to finance, although there is a bit of concern over combining the operational role of the unit with the internal audit aspects. In practice, the finance location works, particularly when separate lines into the audit committee and the internal audit team are available. The following table sets out relations between managers and the risk/reward unit.

System Module Managers Enterprise Risk/Reward Unit Inputs Training

Risk assessment data

Knowledge management ‘nets’

Incidents Selection, scheduling, incident alerts, near misses. Processes Day to day management, peer reviews, project management. Risk assessments, premium calculations, risk/reward models. Outputs Safer operating procedures, reduced process variability, fairer appraisal mechanisms. Reduced insurance premiums, better risk practices, improved performance. Feedback League tables, benchmarking, premium costs, risk databases. Financial results, perceived fairness, risk publications, reports. Feedforward Premium reduction agreements, new behaviours. Strategic direction, corporate ‘scorecards’. Monitoring Operational improvements, standards accreditation. Improved management information, internal market. Governance Board direction, cost of capital charges. External pricing mechanisms, e.g. captives and re-insurance.

More important is working out how to measure the value added by an enterprise risk/reward unit. This is a complex subject, but three principal approaches are used:

- operational benchmarking: the enterprise risk/reward unit can be contrasted with a traditional insurer, e.g. claims handling, administrative to premia cost ratios;

- customer satisfaction: managers view of the benefit, e.g. reports, databases, publications, advice, claims paid;

- financial returns: gross risk reduction over time measured by contrasting internal insurance costs with external costs, e.g. through a quotation; reduction in operational risk measured through per unit cost volatility and premia payment size reduction; investment returns measured through the portfolio of capital charge alterations and internal investment returns in risk reduction projects.

What stands out is that an enterprise risk/reward unit can be set quantitative measures in similar ways to an internal venture capital unit. While banks often let operational risk units be an overhead, industry has been aggressive about seeking ways to measure the value added by an enterprise risk/reward unit. In addition to some of the above approaches, industry has experimented with estimating the amount of capital tied up in risk and attempted to value the return on that capital, used risk/reward options to value capital projects, or even set up competing enterprise risk/reward units within the same organisation which managers can use as if they were competing insurers.

You can only predict things after they've happened.

Eugene Ionesco

Not So Risky Business

Organisational views of risk seem to move through four increasing levels of sophistication:

- Awareness: highlighting the importance of risk management, establishing centres of knowledge, applying basic standards or accreditation, and integrating risk management with corporate ‘scorecards’;

- Engineering: key individuals apply risk management techniques to larger projects or issues. Engineering is typically offline, technical analysis using stochastic or simulation techniques which is then brought to the organisation’s attention through value studies or project finance decisions;

- Comparative: where risk features strongly in management awareness and evaluation through personnel assessment, benchmarking or league tables;

- Embedded: where a risk/reward management system provides an internal market, external pricing and verification, dynamic re-alignment of the risk system with strategic direction and best practice sharing through peer review, databases and publications.

Many banks are only now entering the basic level of operational risk awareness; a few have reached the engineering level; very few the comparative level. Yet the best of industry manages operational risk at all four levels. 1990 was going to be banking’s Year of Operational Risk; so was 1991, 1992…2002. Over the subsequent decade there have been enough debacles, any one of which should have started a movement towards more sophisticated operational risk management. Operational risk has started to get management attention, but only because Basel II raises the costs markedly. Yet even with Basel II, operational risk is not top priority for bank management and, in fairness, they are not getting straightforward answers about what they need to do. Regulators don’t go into detail; there are few pacesetters with a proven record; suppliers push computers or databases; advisors push studies; insurers push policies. Banks need a vision of how to manage operational risk before buying products.

It might be argued that the three proposals in this paper – measuring operational risk through cost variance, implementing enterprise risk/reward units and governing units through quantitative measures – are all a bit difficult for banks. Yet banks have the technology, perhaps unused. Banks have data, perhaps of varying quality. Banks have operational risk managers, perhaps rather isolated. Banks are reacting to operational risk because of regulators. What seems to be missing is a holistic vision of a well-managed, well-measured unit that can give regulators confidence. Enterprise risk/reward units handle some of the toughest operational risks in industry. Perhaps banks should seek out their strongest industrial clients and learn about operational risk from them.

References

[i] “Time to Catch Up: Basel II – Modern Capital Rules for Modern Banks”, Schroder Salomon Smith Barney, September 2001.

[ii] “1999 Survey – Operational Risk – An Industry Discussion Paper”, British Bankers’ Association, page 4 [www.bba.org.uk/public/corporate].

[iii] Harold Benink and Clas Wihlborg, “The New Basel Capital Accord: Making It Effective with Stronger Market Discipline”, forthcoming in European Financial Management, conference draft: http://www.fbk.eur.nl/DPT/VG8/PEOPLE/beninkwihlborg.pdf.

Michael Mainelli originally did aerospace and computing research, before moving to finance. Michael was a partner in a large international accountancy practice for seven years before a spell as Corporate Development Director of Europe’s largest R&D organisation, the UK’s Defence Evaluation and Research Agency, and becoming a director of Z/Yen. Michael has been advising banks around the world for over 15 years on strategy, systems, finance and risk (Michael_Mainelli@zyen.com), as well as many industrial companies.

Z/Yen Limited is a risk/reward management firm working to improve business performance through better decisions. Z/Yen undertakes strategy, finance, systems, marketing and organisational projects in a wide variety of fields (www.zyen.com), such as recent projects managing development of a client’s stochastic perception engine or benchmarks of transaction costs across 25 European investment banks. Michael’s humorous risk/reward management novel co-authored with Ian Harris, “Clean Business Cuisine: Now and Z/Yen”, awarded Sunday Times Book of the Week in 2000, has been described as “very tongue in cheek and very funny but also strangely enlightening” by Business Age.

[A version of this article first appeared as"Industrial Strengths: Operational Risk and Banks", Balance Sheet, Volume 10, Number 3, MCB University Press (August 2002) pages 25-34. [Highly Commended Award 2003, Emerald Literati Club].]