How Offshore Centres Fare In The Global Financial Centres Index 10

By

Professor Michael Mainelli and Mark Yeandle

Published by FSC Report, Campden Media (2012), pages 33-36.

[An edited version of this article appeared as " How Offshore Centres Fare In The Global Financial Centres Index" Campden Media, (2012), pages 33-36.]

Global Ratings

Z/Yen first published the six-monthly Global Financial Centres Index (GFCI) in March 2007 with the support of the City of London Corporation. The GFCI rates and ranks 75 financial centres drawing on instrumental factors weighted in response to an online survey. What distinguishes the GFCI methodology is that, rather than being based on the research team weighting instrumental factors or just taking respondents’ raw assessments, the GFCI uses a statistical approach where the 60,000 assessments so far from 3,500 respondents produce the instrumental factor weightings.

Z/Yen published the GFCI 8 in September 2010, with the support of the Qatar Financial Centre. With increased information over time, the GFCI profiles centres in terms of their links with other centres, as well as the extent and quality of the services that they offer. Instrumental factors are grouped into five ‘areas of competitiveness’ – People, Business Environment, Infrastructure, Market Access and General Competitiveness. A centre’s performance in these areas is assessed from external measures, for example, evidence about a fair and just business environment is drawn from a corruption perception index and an opacity index. Factors change over time due to predictive capacity and availability; 75 instrumental factors were used in GFCI 8. Assessments are provided from an ongoing online questionnaire completed by international financial services professionals. Respondents are asked to rate those centres with which they are familiar and to answer a number of questions relating to their perceptions of competitiveness.

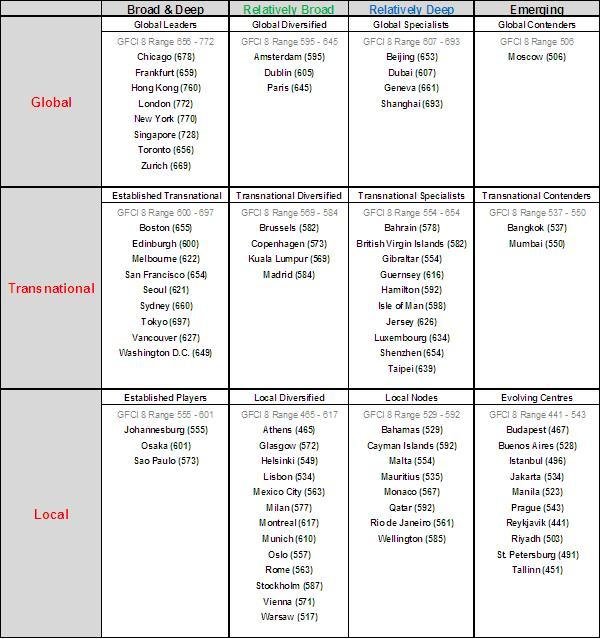

The 75 global financial centres are each assigned a profile on the basis of a set of rules for three measures or ‘axes’ (Table 1):

- "Connectivity" – this represents how well known a centre is around the world and how connected it is to other financial centres;

- "Diversity" – the breadth of industry sectors that flourish in a financial centre;

- "Speciality"– the quality and depth of certain industry sectors in a centre.

The eight ‘Global Leaders’ (in the top left of the table) have both broad and deep financial services activities and are connected with many other financial centres. Paris, Amsterdam and Dublin are “‘Global Diversified”’ centres as they are equally well connected but do not exhibit sufficient depth in different activities to be considered ‘Global Leaders’. Similarly, Geneva, Dubai, Shanghai and Beijing are “‘Global Specialists”’ (specialising primarily in asset management) but do not have sufficiently broad ranges of financial services activities to be ‘Global Leaders’.

Plumbing Offshore

Out of the world’s 221 sovereign states and dependent territories in 2009, 67 have a population of less than 1 million (30 per cent), such as the Bahamas, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, the British Virgin Islands, or Gibraltar. Many have sought to become offshore centres. Offshore centres have used their constitutional independence to develop legislation, regulation and tax vehicles that attract non-resident business. Many have used their comparative advantage to create world-class expertise in international financial services. The most enduring offshore centres offer ways of carrying out financial transaction which are essential but complex from a regulatory point of view, such as reinsurance in Bermuda..

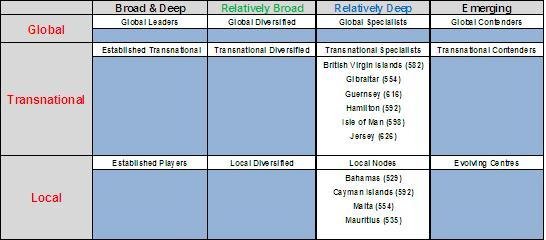

There are numerous other categorizations of offshore, and a desire amongst some offshore centres to be called ‘international business centres’, but the term offhshore sticks and is useful as many centres such as Geneva or Zurich could equally be termed international business centres. Arguably, there could be about 15 offshore centres in the GFCI, heavily concentrated in the ‘Transnational Specialists ’ or ‘Local Nodes’ profiles (Table 2), often specialising in wealth management, asset management, fund management and specialist insurance.

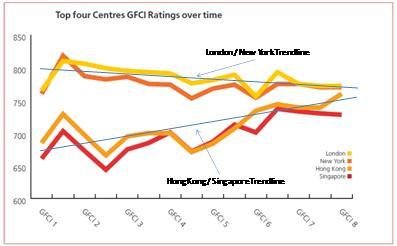

Perceptions of offshore financial centres during the financial crises have been bumpy (Diagram 2):

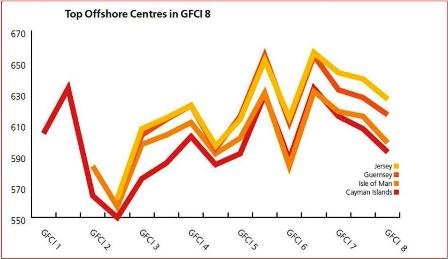

Offshore centres have traditionally positioned themselves in line with four “unique selling points”:, homes for long-term finance, regulatory simplicity, tax mitigation and secrecy. Offshore centres are infamous for two of their four roles, tax mitigation and secrecy. Many offshore centres are regarded as “tax havens” or "money-laundering havens” and there has been significant pressure applied to these centres by onshore national regulators as well as international bodies such as the OECD. The ratings and ranking of all offshore centres declined in GFCI 8, with the exception of Malta’s rank (Table 3):

| GFCI 8 Rank | GFCI 8 Rating | GFCI 7 Rank | GFCI 7 Rating | Change in Rank | Change in Rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jersey | 22 | 626 | =18 | 643 | -4 | -17 |

| Guernsey | 26 | 616 | 22 | 632 | -4 | -16 |

| Isle of Man | 32 | 598 | =24 | 618 | -8 | -20 |

| Hamilton | =34 | 592 | =31 | 612 | -3 | -20 |

| Cayman Island | =34 | 592 | =28 | 615 | -6 | -23 |

| British Virgin Isles | =40 | 582 | 37 | 596 | -3 | -14 |

| Gibraltar | =55 | 554 | 53 | 568 | -2 | -14 |

| Malta | =55 | 554 | 56 | 565 | +1 | -11 |

| Mauritius | 61 | 535 | 60 | 552 | -1 | -17 |

| Bahamas | 64 | 529 | 59 | 557 | -5 | -28 |

Table 3 - Top Ten Offshore Centres in GFCI 8

The standing of the offshore centres has also fallen recently, with international financial professionals, less keen to do business there than in the past. Asian respondents give particularly low ratings to offshore centres. But even traditional users of offshore centres are more wary.

“The Caymans and the Bahamas are just not places to be seen doing business right now – they still have (probably unfairly) a dirty reputation.”

Trust Fund Manager based in New York

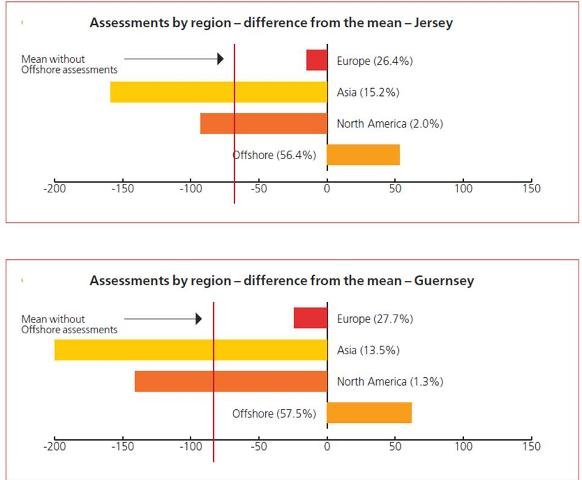

How do offshore centres see themselves? Top offshore centres achieve higher than average assessments from other offshore centres (Diagram 3), but inter-offshore trade is hardly a way to grow business:

Top offshore centres now focus on competing as homes for long-term finance and regulatory simplicity, and tend to ignore competing on tax mitigation and secrecy. A more integrated perspective of comparative advantage emerges from the argument that savvy offshore centres enable longer-term financial planning. “Long finance” structures, i.e. structures that can endure for a generation or two, benefit from avoiding the capriciousness of larger nations’ domestic agendas. A large nation can change tax rules or ownership rules at short notice. Well-regarded offshore centres have achieved a reputation for avoiding hastily-enacted changes that would harm their own self-interests.

The current financial crisis suggests that large states have a comparative disadvantage in global finance. They seem unable to combine wholesale and retail financial regulation without incurring booms and busts. Nor are large states paragons of virtue: witness the scale of onshore regulatory fiascos and money-laundering. Furthermore, though reputations are clearly hurting, offshore centres’ instrumental factors are strong. Z/Yen’s offshore client work indicates that the leading offshore centres have identified several sub-strategies to support ‘long finance’ strategies of long-term finance and regulatory simplicity:

- Get real - more aggressive promotion and directly stating that larger nations do have shortcomings with long-term planning and capricious regulatory change;

- Get integrated - consider “‘mid-shore”’ strategies where there is a symbiotic offshore relationship with larger nations allowing businesses to function under less-than-ideal or complex onshore regulation;

- Get better - tackle long-term skills shortages with better training for indigenous populations rather than relying on imported skills; improve power, transportation and communications infrastructure;

- Get connected – subsidising and hosting high- profile regular events, creating strong academic links, simplifying visa and work permit processes;

- Get serving – increase levels of service both for those entering the centre and long-term residents; consider ‘selling’ good regulation, not just in promotional literature, but as a value-added service, e.g. external inspection reports to family office owners.

Offshore centres need to extend both breadth and depth, which in turn will move them towards a GFCI profile of “Established Transnational”. Paradoxically, the best way to be an offshore centre may be to behave as a better onshore centre, promoting long- term finance and regulatory simplicity. As one GFCI respondent put it:

“The Channel Islands are now promoting the fact that they are not just ‘offshore’ centres.”

Asset Manager based in London

The GFCI 9 is due for publication in March 2011. Please make your views known by participating in the GFCI and rating the financial centres you are familiar with at:

www.globalfinancialcentres.net