Global Financial Centers: One, Two, Three ... Infinity?

By

Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Journal of Risk Finance, The Michael Mainelli Column, Volume 7, Number 2, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pages 219-227.

Michael Mainelli, Executive Chairman, The Z/Yen Group

[An edited version of this article first appeared as "Global Financial Centres: One, Two, Three ... Infinity?", Journal of Risk Finance, The Michael Mainelli Column, Volume 7, Number 2, Emerald Group Publishing Limited (March 2006) pages 219-227.]

Low-Hanging Big Fruits

The Corporation of London sought the opinion of nearly 400 financial services businesspeople on financial centres in 2005 [Yeandle, Mainelli and Berendt, 2005], but what is a financial centre and why do financial centres matter? The answers to both questions are not straightforward.

Financial centres have existed throughout history from ancient, nearly legendary, entrepôts such as Babylon, Samarkand, Constantinople, Marrakech or Timbuktu through to London, New York City, Paris, Tokyo or Shanghai. It is difficult to work out what is the appropriate ‘unit of analysis’ for financial centres. Should we be examining these financial centres at the level of the culture (Anglo-Saxon, Han Chinese, Continental European or Arab), or of the nation-state (USA, UK, Germany or Japan), or at a regional level (Far East, Near East, Europe, North America)? One of the more interesting observations has been that cities, rather than nations, are the drivers of economies [Jacobs, 1984]. Cities are where people go to trade, and live to trade. A city is a unique combination of residential, industrial, business and administrative activity. A city is distinguished from other human habitations by a combination of population density, extent, social importance or legal status. In this study, the ‘unit of analysis’ for a financial centre was the ‘city’. Of course, defining a city is also not straightforward and involves cultures and people in ways that can elude straightforward analysis. In the words of one participant in the Corporation of London’s study:

“Access to international financial markets: you can access them from anywhere nowadays: but there’s a personal factor which requires proximity to other people...”

One can try to focus on ‘global’ cities, but Bangkok, Beijing, Brussels, Chicago, Hong Kong, Johannesburg, London, Moscow, Mumbai, New York, Los Angeles, Paris, São Paulo, Seoul, Shanghai, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo and Toronto are commonly referred to as global cities. One could use ranking systems of cities, for instance the Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network at Loughborough University published an interesting research bulletin [Beaverstock, Smith and Taylor, 1999] giving one attempt at ranking cities by importance:

Alpha World Cities

| 12 points: | London, New York City, Paris, Tokyo |

| 10 points: | Chicago, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Milan, Singapore |

Beta World Cities

| 9 points: | San Francisco, Sydney, Toronto, Zurich |

| 8 points: | Brussels, Madrid, Mexico City, Sao Paulo |

| 7 points: | Moscow, Seoul |

Gamma World Cities

| 6 points: | Amsterdam, Boston, Caracas, Dallas, Dusseldorf, Geneva, Houston, Jakarta, Johannesburg, Melbourne, Osaka, Prague, Santiago, Taipei, Washington DC |

| 5 points: | Bangkok, Beijing, Montréal, Rome, Stockholm, Warsaw |

| 4 points: | Atlanta, Barcelona, Berlin, Buenos Aires, Budapest, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Istanbul, Kuala Lumpur, Manila, Miami, Minneapolis, Munich, Shanghai |

The Corporation of London’s study was bounded by comparability with a previous comparison in June 2003 of London, New York City, Frankfurt and Paris, “Sizing Up the City: London’s Ranking as a Financial Centre” [Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, 2003]. The 2003 report considered six main competitive factors (skilled labour, regulatory competence, tax regime, government responsiveness, regulatory “touch” and living environment), while the 2005 study considered 14 factors. If one asks for key opinions on financial centres much beyond a handful of cities, surveys become too complicated. If one asks for opinions on too few centres, one excludes respondents’ thoughts on emerging centres. For example, a similar study in 1990 might have missed the rapid rise of Dublin in back-office services.

In the end, the Corporation of London’s study focused on comparing four centres (London, New York City, Paris, Frankfurt) and asked for respondents’ wider thoughts. 18 countries were represented by 365 participants who mentioned 54 different cities. In addition to the survey responses, 32 face-to-face interviews in four cities gave a better understanding of how people felt about the issues. There was a London weighting, London respondents were over 50%, but strangely there were few points where Londoners and non-Londoners differed markedly in their views.

What Is A Global Financial Centre?

Of course, if there can be 54 flavours of international financial centre, perhaps there is a need to distinguish a global financial centre from a common, garden varietal. A global financial centre is an intense concentration of a wide variety of international financial businesses and transactions in one location. The city of Hamilton in Bermuda may be an international financial centre for reinsurance, but it is not a global financial centre. Sydney may be Australia’s international financial centre, but it is not a global financial centre. A key theme in the Corporation of London’s study was that London and New York City continue to pull away from the pack. This comment from one participant was fairly typical:

“The importance of London and New York is still growing.”

There seems little point in continuing with the 2003 or 2005 study’s methodology, i.e. comparing London and New York to Paris and Frankfurt. If anything, future research might focus on teasing apart the relationships among the two global financial centres, the leading specialist sub-centres, e.g. Dublin, Bermuda, Zurich or Tokyo and the regional financial centres. After acknowledging the primacy of London and New York City as the two global financial centres, participants could dwell on the characteristics of any of 52 other locations. International activity involves, at its simplest, at least two locations in different jurisdictions. Much international activity involves several locations and several jurisdictions. For instance, a foreign exchange deal between a mortgage bank in Sydney and a Singaporean retail bank is international. But global financial centres come into their own when there are three or more parties or a need for deep liquidity.

The hub-and-spoke arrangement out from global financial centres, i.e. London or New York City directly to regional participants, is not necessarily one where the regional financial centres are operating as sub-hubs. A Sydney mortgage bank may well be working on regional financial deals and be located in Sydney for that centre’s own cluster advantages, but the bank’s international dealings could be direct with counter-parties in London or New York City or with an international counter-party in Sydney who would arrange the transaction, say a large investment bank. This investment bank is most likely to transact the international component of the work in London or New York City. In neither case is the local hub in Sydney involved with these international transactions. You cannot compartmentalise financial services distribution neatly into a typical retail model – a central warehouse, then a regional distribution centre and finally local store.

Under Competitive Pressure

| Factor of Competitiveness | Rank | Average Score |

|---|---|---|

| Availability of Skilled Personnel | 1 | 5.37 |

| Regulatory Environmen | 2 | 5.16 |

| Access to International Financial Markets | 3 | 5.08 |

| Availability of Business Infrastructure | 4 | 5.01 |

| Access to Customers | 5 | 4.90 |

| A Fair and Just Business Environmen | 6 | 4.67 |

| Government Responsiveness | 7 | 4.61 |

| Corporate Tax Regime | 8 | 4.47 |

| Operational Costs | 9 | 4.38 |

| Access to Suppliers of Professional Services | 10 | 4.33 |

| Quality of Life | 11 | 4.30 |

| Cultural & Language | 12 | 4.28 |

| Quality / Availability of Commercial Propert | 13 | 4.04 |

| Personal Tax Regime | 14 | 3.89 |

From the above table it is clear that the availability of skilled personnel and the regulatory environment are the two leading factors, as they were in 2003. It is worth noting that people believe that government responsiveness, the corporate tax regime and the personal tax regime are likely to be of greater concern to them over the next three years, despite the low ranking of corporate and personal tax now. Business infrastructure and access to financial markets will apparently be of less concern. Interestingly, there seemed little overt interest in links between the domestic market and the global financial centre. In academic literature of financial centres, concentration is considered important, and domestic market concentration contributes to agglomeration. In some contrast to a lot of earlier studies in the 80’s and 90’s, the domestic markets affiliated with London and New York City did not come up as a significant factor. Perhaps London is best analysed as two entities – a global financial centre and a domestic financial centre, with little cross-influences among them. This may, at first, appear naïve, but is simply an extension of the earlier argument that transactions change markedly once a number of international parties are involved.

“Despite 9/11, global financial markets appear to continue to depend on concentrated financial centers. New York City and London rank highest according to stock market capitalization and the quantity of specialized corporate services. Tokyo, Frankfurt and Paris rank highest in corporate headquarters and large commercial banks, but New York City ranks far above the rest when it comes to assets of the world’s top 25 securities firms. The corporate services sector in each of these cities varies considerably, with New York and London the largest exporters of legal and accounting services, either directly or through affiliates in other cities. On the other hand, Tokyo and Paris account for 33 percent and 12 percent of assets, respectively, of the top 50 largest commercial banks; London and Frankfurt each account for 10 percent; and New York City accounts for 9 percent. The reasons that financial concentration and agglomeration remain key features of the global financial system, and the network of global financial centers remains crucial for the global operations of markets and firms, are social connectivity, the role of financial centers in cross-border mergers, and the presence of de-nationalized elites.”

The increasing dominance of the English language in finance and the need for flexibility in staffing was a common thread amongst a number of interviewees. Flexibility is particularly important because banking is highly cyclical and needs to increase and reduce staff numbers in response to market changes:

“We recognise that banking is a cyclical business and in the good times we need to increase headcount and in the bad times we need to reduce numbers. We have consolidated our European operations in London because we can always get hold of really good experienced people when we need them and it is easier to ‘downsize’ - in Paris and Frankfurt this is an expensive, time consuming and stressful experience.”

(Director of Global Equity Operations at a London-based Continental European investment bank)

or from another respondent:

“London and New York will remain more competitive than Europe whilst Europe maintains restrictive, socialist, labour laws.”

As an international financial centre grows, staff gain skills and move jobs, the availability of skilled staff grows, thus enabling further growth of the international financial centre. Soon, aspiring financial services job-seekers begin their careers by moving to the international financial centre, further reinforcing its reputation as a place to go to find suitably qualified staff. International financial staff are hard to find, hard to keep and, arguably, hard to manage. If we take salaries at face value, good staff are valuable. Other studies (e.g. Z/Yen’s benchmarking work amongst global investment banks) have shown that experienced international financial staff significantly outperform regional financial staff trying to do international work. For this reason, productivity in the two global financial centres may be above productivity in regional financial centres, despite significantly higher salaries in London and New York City. In fact, it may be virtually impossible to establish a business that needs a pool of personnel skilled in international financial services anywhere except London and New York City.

Turning to the second most important factor, regulatory environment, we see an interesting advantage for London. Despite much hand-wringing years ago over a large single regulator, the Financial Services Authority and the various influences of Brussels and European directives, London has a clear advantage here.

“The FSA listens to and understands our concern. In the USA regulators develop rules and expect you to stick to them.”

(Head of Equity Operations, major USA investment bank)

In some ways, the regulatory advantage shouldn’t be a surprise. Perhaps London has the advantage of the “Wimbledon Effect”, i.e. being seen as a place of fair dealing and regulation for locals and overseas participants. Perhaps there is a role for one independent-of-domestic-markets, global financial centre. Remember that in many ways London as a global financial centre grew from the Eurodollar markets when the US regulators put enough fear into people that they decided it was best to leave vast offshore pools of dollars outside the control of US authorities. Euro markets were particularly attractive because they could often provide higher yields. Then in the 1980s, US companies began to borrow offshore, finding Euro markets an advantageous place for holding excess liquidity, providing short-term loans and financing imports and exports. One director of a major US retail bank was particularly jealous:

“The trouble with regulation in New York is that it’s not joined up –there are too many people asking you to do too many things and half the time they contradict each other. It would be great to have just one regulator.”

(Director, major USA retail bank)

Other research has reported fears about over-regulation, such as the CSFI’s Annual Banking Banana Skins Survey [CSFI, 2005]. Many participants did share those fears:

“The UK Government has taken financial services for granted, and any unwarrantened tightening of regulation will kill the golden goose. The regulatory industry has grown bigger without growing smarter.”

Overall, more than 80% of respondents saw the regulatory environment as Very or Critically Important. Respondents from outside the UK placed greater emphasis on the regulatory environment, with 57% considering it Critically Important. This figure compares with 39% in the UK. Just over 60% of international bankers saw the regulatory environment as Critically Important, compared with 35% of UK bankers. The regulatory environment is considered much better in London and New York than it is in Paris and Frankfurt. Over 90% of respondents rate the regulatory environment in London and New York as Good or Excellent.

Why are operational costs well down the list at ninth place? Looking at detailed bank cost data and dividing banks into 3 categories, those that had their operations in a primary cost location (i.e. London), those that split their operations between a primary cost location and a secondary cost location (i.e. outside London but within the UK) and those that split their operations between primary, secondary and tertiary locations (such as India) – we see fairly similar ‘person cost per trade’ figures’ ($3.11 – all in primary location, to $3.35 with primary and secondary, to $3.19 with primary, secondary and tertiary). What is clearly noticeable is that costs per person are much higher in London but efficiency, as measured by the number of trades executed per person, is also much higher. Several interviewees believe that the competitiveness of the labour market has led to a lower staff turnover in London and New York City than in other centres where working in financial services might be seen as “just another job”, and lower turnover reduces cost. There is much greater flexibility in labour markets in London than Paris and Frankfurt. This is not reflected in “headline” staff costs, but can certainly affect the overall cost of employment.

If operational costs are, in productivity terms, similar then why are financial services businesses so fixated on outsourcing and offshoring in order to reduce costs costs? [Gordon et al, 2005]? Why are participants largely unconcerned with high occupancy costs? London is consistently ranked high in occupancy cost/m2, yet participants didn’t consider this an important factor. If anything, participants were more satisfied in this study with London’s availability of commercial property, though again, one participant noted:

“London is outpricing itself – I’m not sure if this is sustainable without correction or dissipation of its monopoly.”

Perhaps the big issue is that the global financial centre is a big fixed cost. When things get significantly expensive and standardised, they are outsourced/offshored. Otherwise, they are left alone. Perhaps financial services’ margins are so high that cost is not so important. Perhaps financial services costs are so concentrated on staff that the ‘availability of skilled personnel’ and their productivity overwhelms the cost factor. Perhaps operational costs are subordinate to things such as business infrastructure. A smooth, functioning infrastructure justifies the costs. Yet another respondent worried about a lack of innovation by making costs high for start-ups:

"Entry level costs are important. A financial centre that imposes unrealistic costs on start-ups will, in the medium term, become ossified and uncompetitive.”

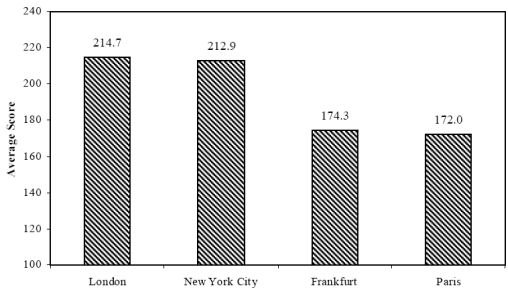

So, in ‘Miss World Order’ we see Paris in fourth, Frankfurt in third, New York City in second and London in first place. While there may be little distinction in importance between London and New York City, both have pulled markedly away from comparison with Frankfurt, Paris, Tokyo or any other regional centre. In future, our list of “beta” cities may need to be rather long. One participant expressed their confusion:

“I am surprised to see Paris and Frankfurt in this list. I would easily place Tokyo ahead of them and possibly the combination of HongKong & Singapore ahead of them as well.”

In this study, London just pips New York City for first place. In 2003, New York City just pipped London. Ignoring the possibility that physical effects might vanish, e.g., the ability to deal from anywhere electronically eliminates the need for a physical location, if certain types of transaction need a global financial centre, then London or New York City might be assumed to ‘get their share’ for the foreseeable future.

Three factors are self-reinforcing, that is the more you have of the factor, the more you have the factor. Einstein supposedly said, that compound interest was “the greatest mathematical discovery of all time”. Similarly, three self-reinforcing factors of liquidity, personnel and regulation might keep substantial ‘blue water’ between London and New York City and everyone else.

“Financial centres are where market liquidity is and market liquidity is very hard to move. Nobody can move liquidity unilaterally and so once a global centre such as London or New York has been established it is virtually impossible to move. It will take a number of significant factors, acting over a number of years to alter the status quo now that it has been established”

(Head of Trading, London-based investment bank)

To expand just on the self-reinforcing effects of regulation - business is transacted where regulators permit, but also where people trust the regulators. Over time, regulators either gain the skills to regulate international financial transactions and institutions, or lose credibility by being too intransigent or too lax. Sooner or later, certain regulatory regimes pull away from the pack. In fact, it may be difficult for regional regulatory regimes to gain the necessary experience of international financial transactions to get back in the game, as one major insurer pointed out:

“For insurance and the products we sell, the UK is by far the most competitive marketplace within our international group.”

Finally, what about all the stuff that’s taken for granted? For example, electricity and water supplies may seem to prevent development of financial services clusters abroad or be an important consideration when looking at outsourcing or offshoring to developing world locations, yet don’t feature in criteria for this study. In the major financial centres, many things are assumed, for instance, an absence of natural threats such as hurricanes or flooding. Yet London used to have significant flood risk, and may again as the Thames Barrier comes to the end of its projected usefulness. Somewhat naturally, participants tend to care about those things of which they are conscious. Further, a criterion that helped to cause success may not be particularly strong today, but it’s too late. For instance, low taxation might draw participants in, but not persist. Likewise, a criterion that is strong and important today, for instance, the availability of skilled personnel, may be an effect rather than a cause.

Participants seem to choose to place their transactions and their business based on a number of criteria at once, so any taxonomic approach has difficulties. It is a combination of factors that makes a financial centre successful, not just a single factor. Jared Diamond derives an Anna Karenina Principle from the opening line of Tolstoy’s novel: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The Anna Karenina principle describes situations where a number of activities must be done correctly in order to achieve success, while failure can come from a single, poorly performed activity. At the moment, London and New York are juggling well, as one banking respondent noted in accord with the Anna Karenina principle:

“I think that the [above] factors cannot be considered in isolation - the combination of factors has a greater impact on a financial centre being competitive than the individual elements.”

Plus Ca Change? Well Maybe, And Remember We Told You So

In 1990, a consensus on the global financial centres would have been London, New York City and Tokyo. Today it’s London and New York City. But might things change?

“Rather than a trinity of equally powerful global cities that have formed in response to a common stimulus, an emphasis on history and structure points to variations in the past and present of the global city.” [Slater, 2004]

The big question is - one global financial centre or three or status quo? As we seem to have gone in 15 years from three to two financial centres, one could make a strong case that soon there will be only one, a “Highlander” imperative from the 1986 film of the same name where “there can be only one” who will win The Prize.

We could argue for London and the advantages of the Wimbledon Effect. We could argue that New York City’s proximity to the largest and most liquid domestic economy ensures it will ultimately prevail. The size of North America’s onshore market guarantees New York City’s success. On the other hand, we could argue that Europe is London’s domestic market as North America is New York City’s. Both cases beg the question, where is the equivalent Chinese financial centre? Participants seemed to believe that Shanghai was most likely to take that position, but not without a struggle. But the rise of a Chinese global financial centre is not inevitable. Perhaps, similar to the development of the Euromarkets, there will be a need for an offshore Chinese market. Is that Hong Kong (perhaps not offshore enough), Singapore, Taipei, Sydney, Tokyo or Dubai? Or is offshore already defined by London or New York City. One version of this future may be summarised in two tables, one for onshore markets and one for offshore markets:

Onshore Markets

| Region | 1 Global Financial Centre | 2 Global Financial Centres | 3 Global Financial Centres |

| Europe | London or New York City | London | London |

| North America | London or New York City | New York City | New York City |

| China | London or New York City | London and New York City | Shanghai? |

Offshore Markets

| Region | 1 Global Financial Centre | 2 Global Financial Centres | 3 Global Financial Centres |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | New York City | New York City | New York City |

| North America | London | London | London |

| China | London or New York City | London and New York City | Singapore? |

Basically, if we have one global financial centre, we could assert that it will be London or New York City. If we have two, London may well serve as New York City’s offshore centre, and perhaps New York City as vice versa. If we have three global financial centres, it may well depend on whether the Chinese authorities establish a regulatory regime that attracts international business or repels business such that they wind up creating offshore pools of Chinese money for another Asian centre. Back in 1999 Sir Willie Purves (former Chairman of HSBC) questioned whether “the UK is to Europe more as Manhattan is to the USA, or more as Hong Kong is to China?” Today we could raise an analogous question, “will China develop an onshore Manhattan or need an offshore London?"

Overall, locating a business in a financial centre seems to be similar to other business location decisions – staff, access to customers, access to suppliers, costs, tax, government, culture and quality of life are all a rich mix. Yet these factors appeal to more than just financial services. London is clearly rated as the best city in Europe [Cushman & Wakefield Healey & Baker, 2005] in which to locate a business, whether financial or otherwise. Of the top 10 cities in Europe, London has a significant lead over Paris, which in turn has a significant lead over Frankfurt followed by Brussels, Barcelona, Amsterdam, Madrid, Berlin, Munich and Zurich. Only regulation of financial services seems different. Perhaps it’s really only for London and New York City to lose their role as the two global financial centres, rather than anyplace else’s to win. London and New York City are not to everyone’s taste, but they are, and have been for over two centuries, largely to the taste of those who work in financial services.

Thanks

My thanks to my co-authors, Mark Yeandle and Adrian Berendt, but even more to the Corporation of London’s research team who supported our work, in particular Malcolm Cooper and Shaun Curtis who contributed much to our thinking.

References

Beaverstock, J V, Smith, R G and Taylor, P J, “A Roster of World Cities”, Cities, 16 (6), 1999, pages 445-458.

Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, “Banana Skins 2005 – The CSFI’s Annual Survey of the Risks Facing Banks”, February 2005.

Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, “Sizing Up The City – London’s Ranking As A Financial Centre”, Corporation of London (June 2003), 41 pages.

Cushman & Wakefield Healey & Baker, “European Cities Monitor 2005”.

Diamond, Jared, Guns, Germs, and Steel, Random House, 1997.

Gordon, Ian, Halsam, Colin, McCann, Philip, Scott-Quinn, Brian, “Off-shoring and the City of London”, The Corporation of London, March 2005.

Jacobs, Jane, Cities and the Wealth of Nations: Principles of Economic Life, Random House, 1984.

Mark Yeandle, Michael Mainelli and Adrian Berendt, The Competitive Position of London as a Global Financial Centre, Corporation of London (November 2005), 67 pages.

Sassen, Saskia, “Global Financial Centres After 9/11”, Wharton Real Estate Review, Working Paper 474, Spring 2004.

Slater, Eric, “The Flickering Global City”, Journal of World-Systems Research, X (3), Fall 2004, pages 591-608.

Professor Michael Mainelli, PhD FCCA FCMC MBCS CITP MSI, originally did aerospace and computing research followed by seven years as a partner in a large international accountancy practice before a spell as Corporate Development Director of Europe’s largest R&D organisation, the UK’s Defence Evaluation and Research Agency, and becoming a director of Z/Yen (Michael_Mainelli@zyen.com). Z/Yen was awarded a DTI Smart Award 2003 for its risk/reward prediction engine, PropheZy, while Michael was awarded IT Director of the Year 2004/2005 by the British Computer Society for Z/Yen’s work on PropheZy. Michael is Mercers’ School Memorial Professor of Commerce at Gresham College.

Michael’s humorous risk/reward management novel, “Clean Business Cuisine: Now and Z/Yen”, written with Ian Harris, was published in 2000; it was a Sunday Times Book of the Week; Accountancy Age described it as “surprisingly funny considering it is written by a couple of accountants”.

Z/Yen Limited is a risk/reward management firm helping organisations make better choices. Z/Yen undertakes strategy, finance, systems, marketing and intelligence projects in a wide variety of fields (www.zyen.com), such as developing an award-winning risk/reward prediction engine, helping a global charity win a good governance award or benchmarking transaction costs across global investment banks.

Z/Yen Limited, 5-7 St Helen’s Place, London EC3A 6AU, United Kingdom; tel: +44 (0)20 7562-9562.