Gibraltar's Competitiveness As A Financial Centre

By

Professor Michael Mainelli and Mark Yeandle

Published by Gibraltar Global Investor's Guide (April 2012), pages 36-39.

Professor Michael Mainelli and Mark Yeandle, The Z/Yen Group

[An edited version of this article appeared as "Gibraltar As An Overall International Finance Centre" Gibraltar Global Investor's Guils 2012 Milestone GRP (2012) pages 36-39.]

Global Ratings

Z/Yen conducts considerable research into the competitiveness of financial centres. The output of this research is the Global Financial Centres Index (GFCI). The GFCI was first published in March 2007 since then there have been ten updates at six monthly intervals. Z/Yen published GFCI 11 in March 2012, with sponsorship from the Qatar Financial Centre. The GFCI rates and ranks 77 financial centres drawing on instrumental factors and financial centre assessments from an online questionnaire survey:

- Instrumental factors: our research indicates that many factors combine to make a financial centre competitive. These factors can be grouped into five over-arching ‘areas of competitiveness’: People, Business Environment, Infrastructure, Market Access and General Competitiveness. Evidence of a centre’s performance in these areas is drawn from a range of external measures. For example, evidence about a fair and just business environment is drawn from a corruption perception index and an opacity index. 80 factors have been used in GFCI 11.

- Financial centre assessments: GFCI uses responses to an ongoing online questionnaire completed by international financial services professionals. Respondents are asked to rate those centres with which they are familiar and to answer a number of questions relating to their perceptions of competitiveness. Overall, 26,853 financial centre assessments from 1,778 financial services professionals were used to compute GFCI 11, with older assessments discounted according to age.

What distinguishes the GFCI methodology is that, rather than being based on the research team weighting instrumental factors or just taking respondents’ raw assessments, GFCI uses a statistical approach where the financial centre assessments have been used to produce the instrumental factor weightings.

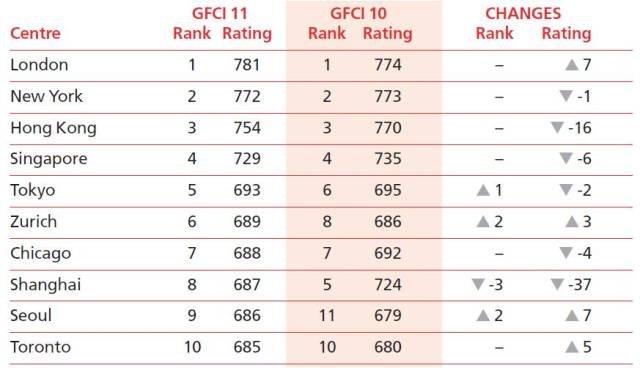

The top ten financial centres in GFCI 11 are:

Table 1 – GFCI 11 Top Ten

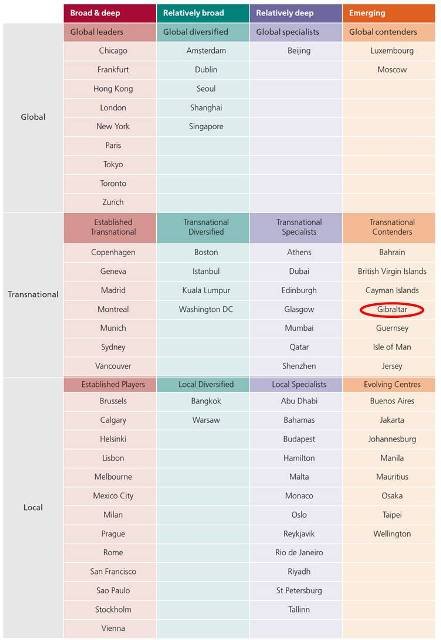

With increased information over time, the GFCI profiles centres in terms of their links with other centres, as well as the extent and quality of the services that they offer. The 77 global financial centres are each assigned a profile on the basis of a set of rules for three measures or ‘axes’ (Table 2):

- ‘Connectivity’ – this represents how well known a centre is around the world and how connected is it to other financial centres;

- ‘Diversity’– the breadth of industry sectors that flourish in a financial centre;

- ‘Speciality’– the quality and depth of certain industry sectors in a centre.

Table 2 – Global Financial Centres Profiles and Ratings

The nine ‘Global Leaders’ (in the top left of the table) have both broad and deep financial services activities and are connected with many other financial centres. Amsterdam, Dublin, Seoul, Shanghai and Singapore are ‘Global Diversified’ centres as they are equally well connected but do not exhibit sufficient depth in different activities to be considered ‘Global Leaders’. Similarly, Beijing is a ‘Global Specialist’, it does not have a sufficiently broad range of financial services activities to be a ‘Global Leader’. Gibraltar, along with other offshore centres, is profiled as a ‘Transnational Contender’ – well known internationally but with insufficient depth and breadth of financial services to be a leader.

The main headlines of GFCI 11 are:

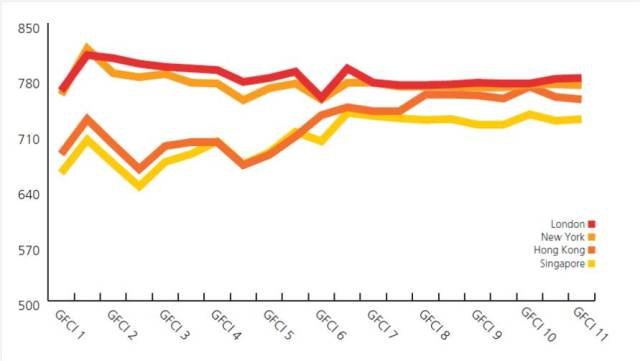

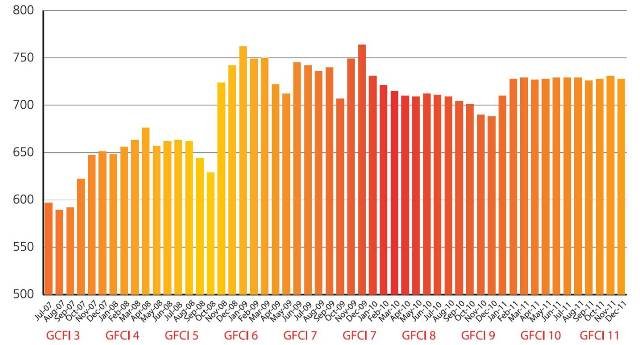

- London, New York and Hong Kong remain the three leading global financial centres as shown in Chart 1 below:

Chart 1 – Top Four GFCI Centres’ Ratings Over Time

In GFCI 10 Hong Kong was just three points behind New York and four points behind London. Hong Kong has now fallen back a little but maintains its position as the third global financial centre. These three centres control a large proportion of financial transactions (approximately 70% of equity trading) and are likely to remain powerful financial centres for the foreseeable future.

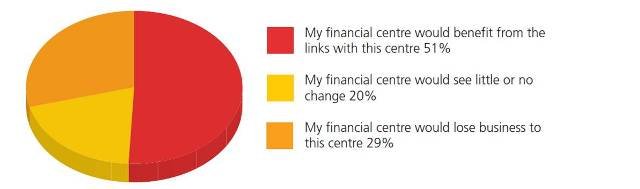

We continue to believe that the relationships between London, New York and Hong Kong are mutually supportive. Whilst some industry professionals still see a great deal of competition, others from the industry appear to recognise that working together on certain elements of regulatory reform is likely to enhance the competitiveness of these centres. We recently asked GFCI respondents “If a financial centre which was closely linked with your centre, became significantly more important, how would this affect your financial centre? Just over half the respondents think that financial centres can benefit from close links with other centres:

Chart 2 - Close Links with Another Financial Centre

- The past trend of large rises in the ratings of Asia/Pacific centres has paused. Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, Shanghai, Beijing, Taipei and Shenzhen all decline in GFCI 11. Centres on the mainland of China have seen significant declines with Shanghai down 37 points and Beijing down 11. Hong Kong sees a 16 point drop and is now 27 points below London. We believe that these results in Asia are just an interlude in the long term trend of the increasing importance of the region rather than a fundamental change in fortunes. Overall respondents think that the Asian centres will continue to become more significant. Some respondents question whether financial centres on mainland China will be able to continue their growth without relaxations in currency controls. It is worth noting that Seoul and Sydney are the only centres in Asia/Pacific showing higher ratings that in GFCI 10.

- The recent crisis of the Euro has changed the balance of interest within the Eurozone. The capital cities of the weaker Euro economies are clearly suffering. Dublin, Milan, Madrid, Lisbon and Athens were all down in GFCI 10 and this decline has continued in GFCI 11 with these five centres all down in the rankings again. In contrast to the centres in the weaker Eurozone economies, Frankfurt and Paris have both risen in the ranks (by two places and three places respectively). This may be as a result of the political lead that Germany and France have been showing in attempting to come to terms with the Eurozone crisis.

- There have been some other strong performances in Europe with Vienna (up 21 points), Amsterdam (up 12), Warsaw (up 13), and the Scandinavian centres of Stockholm, Oslo and Helsinki all doing well.

- Confidence amongst financial services professionals, measured by average assessments of the leading centres was relatively stable during 2011. This is demonstrated by a stability in the ‘spread’ (measured by standard deviation) of assessments.

Chart 3 - Three Month Rolling Average Assessments of the Top 25 Centres

Offshore?

What is ‘offshore’? Many of the world’s smaller states or territories have sought to become successful financial centres by using their constitutional independence to develop legislation, regulation and tax vehicles that attract non-resident business. Many have used their comparative advantage to create world-class expertise in international financial services. These states or territories include the geographically ‘offshore’ centres such as the Channel Islands, Gibraltar, the Isle of Man, the British Virgin Isles the Cayman Islands, Bermuda and the Bahamas.

There are also a number of states that are relatively small, independent and although not geographically ‘offshore’, exhibit several of the key competitive advantages of the island states. Geneva, Zurich, Luxembourg and even places such as Hong Kong are viewed as ‘offshore’ centres by many who deal with them. Whatever the definition, the most enduring offshore centres offer ways of transacting essential but complex wholesale finance transactions, e.g. reinsurance in Bermuda.

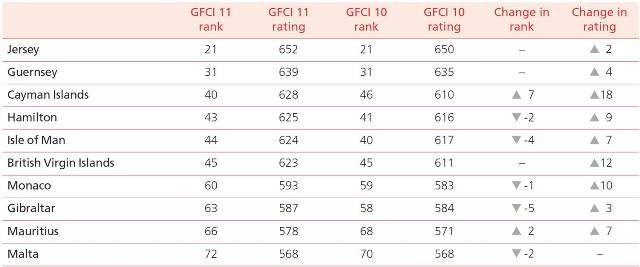

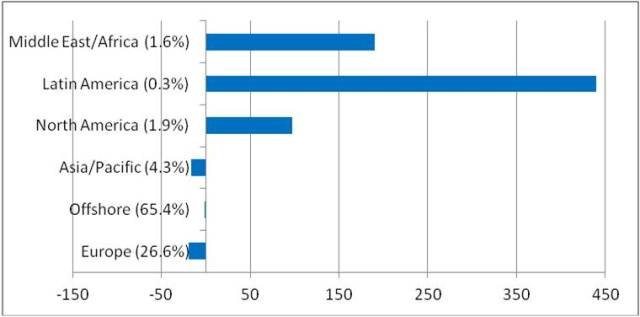

Arguably, there are about 15 offshore centres in GFCI, eight of which are ‘Transnational Contenders’ profile (in Table 2). These centres often specialise in wealth management, asset management, fund management and specialist insurance. The top ten offshore centres in GFCI 11 are:

Table 3 - Top Ten Offshore Centres in GFCI 11

Offshore centres have suffered significant reputational damage in the past four years. In GFCI 10 several of these centres were beginning to recover and this trend has continued in GFCI 11. Jersey, Guernsey, the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, the Isle of Man, Gibraltar and Mauritius (listed in order of GFCI rank) have all made modest gains in the ratings. This recovery in relative popularity has increased as more financial professionals come to appreciate the utility of the offshore centres.

Jersey and Guernsey remain the leading offshore centres. A number of our respondents believe that centres like Zurich, Geneva and Luxembourg, whilst not geographically ‘offshore’, compete in a similar manner to the genuinely offshore centres. It is interesting to note that Zurich, Geneva and Luxembourg have all risen in the GFCI 11 ratings.

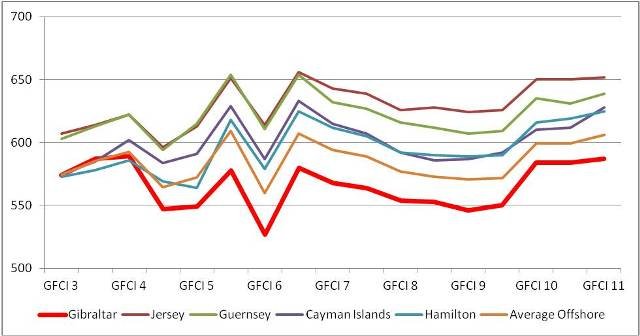

Chart 4 - Selected Offshore Centres Over Time

Global popularity has risen but how do offshore centres see themselves? Top offshore centres achieve higher than average assessments from other offshore centres (Chart 5), but inter-offshore trade is hardly a way to grow business:

Chart 5 – External Assessments of Jersey

Chart 6 – External Assessments of Gibraltar

Top offshore centres have tried to attract long-term finance and regulatory simplicity, rather than competing on solely on tax mitigation and secrecy. Clever offshore centres that enable longer-term financial planning with ‘Long Finance’ structures (structures that can endure for a generation or two), benefit from avoiding the capriciousness of larger nations’ domestic agendas. A large nation can change tax rules at short notice. Well-regarded offshore centres have achieved a reputation for stability in their tax rules and remember that financial professionals hate surprises.

Z/Yen’s offshore work indicates that the leading centres have identified several sub-strategies to support ‘long finance’ strategies:

- stronger promotion and showing that larger nations do have shortcomings with long-term planning and capricious regulatory change;

- tackling long-term skills shortages with better training of indigenous populations rather than relying on imported skills; improving power, transportation and communications infrastructure;

- subsidizing and hosting high profile conferences and events, simplifying visa and work permit processes;

- increasing service levels both for those entering the centre and long-term residents;

Offshore centres need to extend both breadth and depth, which in turn will move them towards a GFCI profile of ‘Established Transnational’. Paradoxically, the best way to be an offshore centre may be to behave like a better onshore centre, promoting long term finance and regulatory simplicity.

It is argued that financial flows through offshore centres increase the rate of GDP growth and employment in larger economies. However, the offshore world is linked to the state of the global markets, so transactional work will slow down as international markets slow. There are other challenges on the horizon too:

- international regulators are sometimes accused in some quarters of bullying the offshore centres and international regulators are still focused on the activities of offshore centres – can these centres be over-regulated?

- the World Bank is showing increased scrutiny of the use of corporate vehicles to conceal misuse of funds – will this impact on offshore business?

- the EU crisis – will investors start a flight to safety and use offshore funds more and if so which centres will they choose?

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British Overseas Territory and a self-governing and self-financing parliamentary democracy within the European Union. Gibraltar is a separate legal jurisdiction and its Parliament is solely responsible for the enactment of all domestic laws and for the transposition of European Union directives.

As a British Overseas Territory, Gibraltar matches UK standards in financial services regulation. Most of the banks established in Gibraltar are branches of major UK, European or US banks. Much of the banking activity in Gibraltar is directed to asset management for high-net-worth individuals, partially because Gibraltar has actively tried to attract such people with special tax regimes. Gibraltar’s financial services sector contributes approximately 30% to the GDP of Gibraltar.

Gibraltar’s financial services are showing growth in several different sectors - insurance , reinsurance, fund management and investment services.

There is no stock exchange in Gibraltar and it has not been as widely used for corporate financial holding purposes as some other jurisdictions, so that corporate financial services are not as well developed as private services.

The Gibraltar Financial Services Commission regulates investment business in Gibraltar and is organized by industry groups, with separate divisions for insurance, fiduciary services, banking and investment services.

What must Gibraltar do to become more competitive?

GFCI respondents are financial services professionals from all over the globe. They say that the most important areas of competitive now are (in order) personal and corporate tax levels, the stability and predictability of regulation, the quality and availability of staff and general economic conditions. :

The GFCI questionnaire asks respondents to name the single regulatory change that would improve a financial centre’s competitiveness. Although a large number of possible changes were named, the four mentioned most often a reduction in personal taxation and increased predictability of the regulatory environment. The GFCI questionnaire also asks respondents how financial centres can best signal their long-term commitment to financial services. Again, stability of regulation and taxation are seen as the best signals although lack of corruption is also seen as crucial.

It is clear that Gibraltar performs well in many of the areas that financial professionals think are important. Tax rates are competitive, regulation is stable and of a good standard and infrastructure is as good as, or better than, most offshore centres. Why does Gibraltar lag behind other centres in the GFCI?

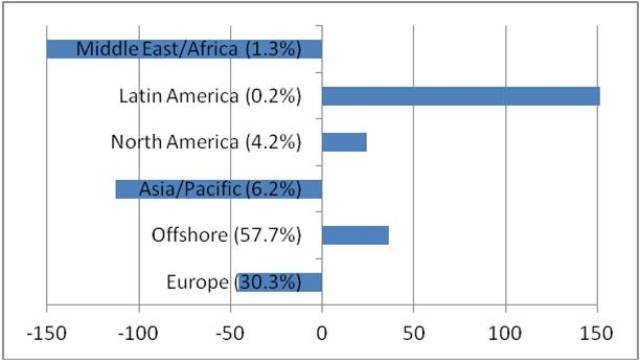

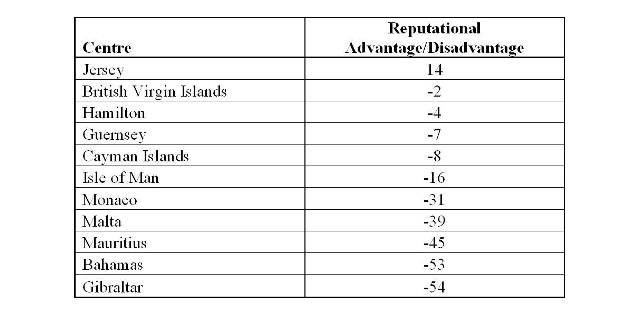

In the GFCI model, one way to look at reputation is to examine the difference between the average assessment given to a centre and its overall rating (the average assessment adjusted to reflect the instrumental factors). If a centre has a higher average assessment than the GFCI 11 rating this indicates that respondents’ perceptions of a centre are more favourable than the quantitative measures alone would suggest. This may be due to strong marketing or general awareness.

Similarly, a centre with a lower average assessment than the GFCI 11 rating indicates that respondents’ perceptions of that centre are less favourable than the quantitative measures alone would suggest – a reputational disadvantage.

The centres with the highest reputational advantage include Singapore (+34), Shanghai (+34) and Toronto (+27). The centres with the largest reputational disadvantages are Athens (-115) and Tallinn (-110).

The reputational advantages and disadvantages of the leading offshore centres are shown below:

Table 4 – Reputational Advantage/Disadvantage of Offshore Centres are shown below:

Reputation is clearly a big issue for Gibraltar – it suffers from a stronger reputational disadvantage than other offshore centres.

Policy makers in financial centres have to decide whether to prioritise the fundamental development of a centre’s competitiveness or to bolster the reputation of the centre. This prioritization will change over time. Our research suggests that currently Gibraltar needs to address the issue of reputation as a priority in order to be seen as a more competitive offshore centre.

GFCI 12 is due for publication in September 2012. Please make your views known by participating in the GFCI and rating the financial centres you are familiar with at:

www.globalfinancialcentres.net

Mark Yeandle is an Associate Director of Z/Yen Group and manages the GFCI. Professor Michael Mainelli is the Executive Chairman of the Z/Yen Group and co-creator of the GFCI. Z/Yen is the City of London’s leading commercial think-tank. More information is available at www.zyen.com or by contacting mark_yeandle@zyen.com.