Fishy Assets (Estimating Client Asset Values)

By

Robert Pay and Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Managing Partners' Forum Review, Number 19, Professional Connections International, pages 2-3.

Fishing for Customers: Valuing them as Assets

Managing client relationships in a partnership has some interesting similarities to managing fish stocks in a fishing zone. Assets are useful or valuable qualities or things. They require care and attention. Asset value needs to be preserved and, where possible, enhanced. Fish stocks are an asset. To give some examples, fisherman can bid for quotas, exchange quotas, have overlapping fishing of different stocks over the same ground and need to maintain their fishing assets.

There are some challenging implications from this simple association. For any significant asset, an auditor expects seven typical pieces of evidence - Cost, Ownership, Disclosure, Value, Existence, Responsibility and Benefit. These pieces of evidence produce the somewhat surreal, but relevant, mnemonic device, COD-VERB. In client relationships, the relevance can be as follows:

- Cost: normally too much focus is on the cost of servicing a client, yet costs are often incomplete, poorly attributed or disproportionately important in determining benefits (fees);

- Ownership: often partners confuse ownership, "the firm's client", with responsibility, "my client", which impedes cross-selling and the development of a full client relationship;

- Disclosure: sharing accurate information with stakeholders, other partners, about the client and how things are going;

- Value: too often value is not calculated but given, "these are the fees we managed to get last year";

- Existence: genuine evidence of a client relationship is too often attributed to Costs (if we spend money to deliver for them, they must be a client) or to Benefits (if we bill them and they pay, they must be a client), rather than to the quality of the relationship (do we have all the business we should reasonably expect from the client or how important are we to the client);

- Responsibility: is someone, typically a partner, responsible for the client and charged with realising year-on-year the value the firm attributes to the client;

- Benefit: is the value of the client (we need an important name of that calibre) translating into benefits (income) either from the client or from the relationship (their suppliers, customers, referrals);

An example from one accounting firm may help to illustrate the confusion. The firm had a major television company audit on which it lost money every year. The firm believed it needed the television client's name to get other business in the media sector, but could not show any increased work. In fact, the firm had lost a few pitches to competitors because of potential conflicts of interest. The client saw the audit as a bit of under-priced work by a firm from whom the client had no intention of buying other services. The client was spending millions on advisory services from other large accountancy practices. What was the value of the client? Negative value? Why were those responsible not changing or dropping the relationship? Whose client was it really - the auditors or the advisors? Was it a client at all? Before the legal profession gets too smug, it is easy to find analogous examples, e.g. commercial departments overlooking large litigation opportunities.

COD-VERB, or "clients as assets", is a big concept with big rewards. By viewing clients as assets owned by the firm, but managed by partners, each partner begins to think like a fisherman. What grounds should I bid for this season? What type of fish should I catch? Should I hand my unproductive clients to others who may have more interest? What do my fellow partners expect me to deliver from my client base? If this is going to be a bad year, what am I doing to replenish the stocks in the portfolio? Each element of the mnemonic is inter-related, without Costs then Benefits are inaccurate, without Responsibility then Disclosure has no impact, etc. The most difficult, but interesting starting point is possibly valuation, on which we will focus for the rest of this article.

Valuation of clients is tricky, but certainly not as impossible as many firms have claimed when we began working with them. In fact, lifetime customer valuation is used intensively in some business sectors. The key objective is to analyse existing clients to work out a starting valuation formula. The valuation formula can be used by managing partners on the portfolios of clients for which individual partners are responsible. The resulting value is a target for the fees which the firm expects a partner to generate from the portfolio of clients the firm has given him or her to fish or which he or she should return. For those of a religious mind, Matthew, 25: 14-30, the parable of the talents, shows that this is not a modern idea: "For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath" (29).

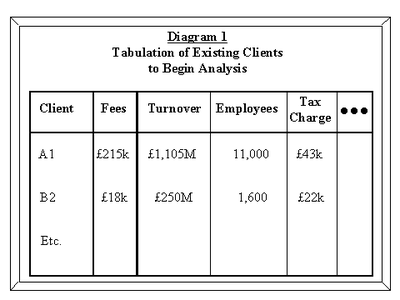

Developing a valuation formula begins with a simple tabulation of existing clients and their characteristics. Diagram 1 shows an easy starting point, fees and some of the possible fee factor determinants, size of client, number of employees, tax charges.

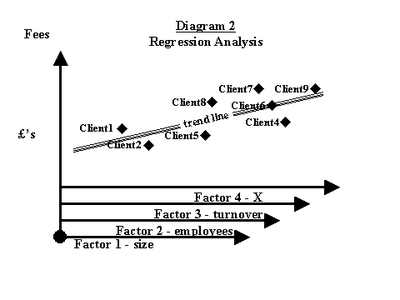

Things can get richer, for instance fees by type of work and large numbers of possible fee factors, perhaps as many as 30 or 40. Using some basic regression analysis, we normally find that three to five factors will explain over 80% of a client's billings, as illustrated in Diagram 2.

The results can be as straightforward as:

- an estimation formula, e.g. Expected Fees = (.00013)x(£turnover) + (£10)x(number of employees) + (0.5)x(tax paid);

- a confidence factor, e.g. plus or minus X%.

- While the valuation formula will be inaccurate when applied to any specific client, it can be used successfully to value the portfolio of an individual partner. A valuation formula can be used in at least three powerful ways:

- to improve partners' performance;

- to promote a more rewarding client relationship;

- to price new business and ensure that the object of aggressive pricing is achieved.

Partners' performance is improved by setting targets, measuring performance and providing mechanisms for partners to ‘trade’ in clients. Managing partners can use the valuation formula as part of setting targets, "you have 35 existing clients and bill £773,000, yet from our valuation estimate you should be billing £1.1M plus or minus £83,000." This is surely a better approach to target setting than "I expect you to do about 5% better than last year" with little sanction or genuine trading in clients if the target is not achieved. Year on year, such target setting should encourage the dissemination of best practice. With increased success, the valuation formula will change to expect even greater billings from the same client characteristics, and the total rewards will keep rising. Partners who are unable to deliver expected value from their clients may give them to partners who are better at developing more complete relationships in order to avoid further failure to develop fees. These partners may specialise in more narrow areas or seek to develop new business, which may be valued at a somewhat higher rate than business from existing clients.

More rewarding client relationships should arise from partners in the firm finding the partner best suited to develop the client. All too frequently, the client service partner is the partner who found the client first or the partner who ‘inherited’ the client as a manager, with little heed paid to who would best ‘fish’ within the client for the firm. All too commonly, the client service partner does not wish to ‘rock the boat’ by introducing risky new service areas. Such client service partners destroy cross-selling initiatives within their portfolio. By focusing on expected value, client service partners may wish to give up clients whom they cannot develop or do not wish to develop. In accountancy firms, this often means that the partner best placed to develop the client in the interests of the firm is a consultancy or tax partner, not an audit partner.

As a final example of usage, a valuation formula can be used to estimate the potential value of a new prospect or set of prospects. When bidding for an initial piece of work, partnerships often discount. But discounting is frequently pointless if there is little further work to gain. Using a valuation formula can help to assess the importance, or insignificance, of a new, small piece of work. Having won a new client with a small piece of work, the valuation formula, combined with targets, ensures that the firm obtains the Benefit it priced so aggressively to obtain.

By valuing clients, treating clients as assets (remember COD-VERB) and integrating this type of approach within the partnership remuneration process, managing partners can feel more comfortable that the correct decisions are being made more regularly at the level in the firm where it will do the most good - the client/partner interface.

Michael Mainelli is a Director of Z/Yen Limited (www.zyen.com), the UK’s leading risk/reward management firm and non-executive Chairman of Jaffe Associates.

Robert Pay is Managing Director of Jaffe Associates (www.get-serious.com), which provides sales, marketing and business improvement services to professional firms.

[A version of this article originally appeared as “Fishy Assets” (estimating client asset values), Managing Partners’ Forum Review, Number 19, Professional Connections International (July/August 1999) pages 2-3.]