Ensuring People Risks, Rewarding HRM: Proactive & Reactive Link Of HRM To Business Strategy

By

Professor Michael Mainelli, Ian Harris

Published by Journal of Professional HRM, Croner, pages 3-8.

At times, HRM must be re-active, dealing with problems or opportunities as they arise, yet leading thinkers stress the importance of being pro-active, helping to shape the strategies of the organisation. A pro-active role means identifying, analysing and implementing solutions to problems and opportunities before they arise. How can these two roles be reconciled? What mechanisms can ensure that reactive and proactive roles support the business strategy?

Everyone Loves HRM

It would be a strange automotive company that said, "our business is automobiles, which are so important to us that we have centralised all decisions about automobiles". It would be an equally strange company that said, "finance is so crucial to all our decisions that all financial decisions will be made by the finance unit". So why is it that in an era where "people are our most important asset" and "everyone is in the people business", we see HRM units fighting the impossible battle of imposing centralised HRM. Shouldn't we ensure that every manager is equipped to use HR effectively in his or her contests. Shouldn't HRM units be fighting the corporate battle alongside their compatriots in the organisation, like medics in the trenches within a medical corps, rather than far behind the battle lines in a quiet, rural hospital? Shouldn't HR Professionals' contributions be assessed by their fellow soldiers, not some four star general sitting comfortably back at corporate headquarters? Noble sentiments surely - but practical sentiments only if we can measure the value of HR in the trenches?

David Hussey put forward eight Myths about HRM [Hussey, 1996]. As evidenced by ever-more-common, fond interpretations of the HR acronym, e.g. "Human Remains", it is no surprise that David's eighth, final Myth was: "Line management knows that HRM is a valuable, value adding strategic partner which plays an irreplaceable role in the management of the organisation." Although the following fictional, lunchtime conversation between an Operations Manager and an HR Professional was written with HRM in mind, it could have been adapted to many head office functions:

HR Professional: "Oh, you might be interested to know we're conducting a strategic review of the role of HRM at head office."

Operations Manager: (More head office S&M - scratching & manoeuvring - it's always politics at HQ) "Isn't that a bit like bringing coals to Newcastle?"

HR Professional: "Sort of. But there is a serious side to this. We've been asked to see if we can radically re-engineer and re-measure our unit. In my opinion, it's a bit of a wasted exercise because we do so many different things within HRM. Many of them take such a long time to come to fruition, but you know the routine."

Operations Manager: (Hussey's sixth Myth - "…it is not possible to evaluate the results of many HRM actions which should be treated as acts of faith") "Sure, we're constantly trying to re-engineer and measure what we do. Who kicked this review off."

HR Professional: "Oh, nobody in particular, we just think it's a good idea to do this sort of thing periodically."

Operations Manager: (What a porker, obviously someone on the board got wind of how large the unit has become) "Isn't that non-executive director, Sam, always asking for re-engineering reviews?"

HR Professional: "Sure, he made a big fuss about how we're always too busy in HR dealing with our problems to help in his reviews. Even now he's making a few suggestions to my boss, the Head of HR, about some of his wacky ideas, but he really doesn't understand what we do. Anyway, this is mostly our review. In fact, my boss has arranged a brainstorming workshop for tomorrow where we're going to focus on the question of where we add value to the corporation and report the results upstairs."

Operations Manager: (What a good question - about time these folks faced our daily treadmill of finding ways to increase value) "By the way, who does your boss report to these days?"

HR Professional: "Well, the Chief Executive of course, but that too is part of the review. We do so much that is unappreciated by anyone but the Chief Executive, who has so little time. All of us in HR do a bit of work with most of the directors - finance, the various operations directors, international, marketing - because the Chief Executive often forces them to clear things with us before they can proceed. Most of the time we help directors to improve things. In fact, I even did a small study for the Chairman last year after the Chief Executive told the Chairman he needed to use us."

Operations Manager: (Bet the Chairman was pleased - looks like they depend totally on the Chief Executive's clout) "Does your boss get on well with the other directors?"

HR Professional: "Definitely. Well, except for Joan who heads up International. Complained that we stuck our noses in and were just lackeys for the CEO. I mean the rest of them understand that we need to give guidance on the big, holistic, long-term, overall picture, the total Weltanschauung, as we say in HR. It can take some time. The directors may not be our friends, but they know how useful we are and don't mind waiting for our assessments. Just the other day, Suzanne, that special project director for Australasia, mentioned to the board that we should get involved in the feasibility study for Azerbaijan. It's dragging and they need our input. Suzanne's too tied up to help."

Operations Manager: (Interfering busybodies with no friends whatsoever - not surprising without a power base or proof of value-added) "How do you even start to work out how many people you need to work with all these directors?"

HR Professional: "An excellent question. With so much going on we never have enough quality people. It's been that way for years. Always too much to do - annual budgets, directors' strategy weekends, corporate plans, annual appraisals, etc. HR touches every aspect of the business."

Operations Manager: (Definitely over-staffed and over-nosy) "Getting back to this review, don't you think it would be helpful if you could measure the value of what you contribute?"

HR Professional: "That's not a bad thought. Although we're not on the front line, we are absolutely essential. If we could measure our contribution concretely then some of these politically-inspired reviews (oops) might not get started. I can see that you folks in operations need to do that sort of thing. On the other hand, we're very busy. This is hardly the right time to open up that can of political worms. Further, with the sheer variety of our projects I'm convinced it's impossible to measure the value of what we provide."

Operations Manager: (He doesn't want to change - he hasn't got a clue) "For what it's worth, my tuppence of advice is 'without measurement it will always be politics'. But enough business; what's for lunch?"

Surely, 'Tis Better To Proact Reactively than To React Proactively?

"Reactive" has become the ugly sister word to "Proactive". At times, though, "reactive" is fine. Sometimes things just need to get done. Sometimes things are so uncertain that it can be better to do nothing, just react. Clearly, "proactive" implies that, in some way, we have control over our environment. While proactive seems desirable, it can be a dangerous illusion in a world where uncertainty reigns. Proactive projects have a tendency towards the grandiose - the Sorcerer's Apprentice projects that we can't remember why we began, but now can't stop. On the other hand, just sitting back and "taking it as it comes" is to ignore the power of vision, commitment and organisation. When we look at linking HRM to the business strategy, we must ensure that we include the reactive and the proactive - both roles have an important place.

Too frequently, HR units scurry about doing their master's bidding, like a bunch of presidential aides who, being close to power, get carried away by the illusion of having power. If the Chief Executive asks them to do something, it must be certainly be assumed worthwhile and in the best interest of the organisation. They rarely see themselves as others do. When times are good and the Chief Executive hobnobs with his or her fellow wizards in the boardrooms and dining salons of the corporate world, he or she adores the social cachet of phrases such as "I'll have my HR bods look into that idea" or "With all the demographic changes and lack of IT skills in the economy, I keep my HR team busy just checking out all of the fringe opportunities". When times are bad, HR units are just an expensive overhead. HR units are particularly expendable when their sponsor needs to show the ability to take cuts him- or her-self.

We must also not confuse being at the proactive phase with being proactive. Hussey's second Myth: "if HRM is allowed to be proactive when new corporate strategies are considered, this automatically means that all HRM activities will become business driven." Too often a proactive project or sub-project gets underway, but the bulk of HRM continues plodding along in an unmeasured state. While operations managers who participate in the proactive, planning phase take responsibility for the outcomes, HRM often settles for "facilitating and supporting the strategy", "developing a human resources sub-strategy" or other non-commital, non-measurable input.

Strategic Hierarchies

Strategy and strategic planning are involved, and involving, subjects. This paper focuses on linking HRM to the business strategy. It may be helpful to apply a simple, generic model of strategy to the remainder of the paper, five questions and a three phase planning cycle. The five basic strategic questions are:

- where were we?

- where are we now?

- how did we get here?

- where are we going?

- how will we get there?

The three cyclical phases of strategy are planning, implementing and evaluating. The frequency of this cycle is increasing in companies for a variety of reasons - a belief in an increasing rate of change, increasing uncertainty, changes in strategic fashion. In the past, strategic planning retained an air or aloofness, even a touch of academia within the corporate world. Today strategic planning is seen as a key, but routine, function of the Board. Strategic planning is less frequently led by a specialist unit and more by the Board executive supported by a specialist strategic unit. The link between planning and HRM is well-developed, particularly as boards have increased HR representation. This established link has led to Hussey's first Myth, "if the top HR Manager is on the Board, this is enough to ensure that HRM is business driven." Below we examine alternative ways of implementing the next two phases of strategy - implementing and evaluating - although much could be written about HR and strategic planning.

A good place to start looking for alternative ways to implement and evaluate strategy is to consider four key reasons organisations do anything - it's a money-maker; it's politically expedient; it's legally required; it's essential - e.g., respectively, sales commissions, much public relations, most health&safety, toilet cleaning. Looking at HRM, the last two reasons probably don't feature in this discussion. HR is unlikely to be legally required soon, despite some looming EU clouds. Without HR, firms hardly grind to a halt. In fact, there are large numbers of successful, fast-growing organisations which shun all formal HR functions. So HR units need to bind themselves tightly to money-making or political expediency. Too often HR units choose political expediency. Yet can we find ways to link HR with money-making?

Perhaps a few detailed examples of how HR can help line managers make or save money may bring the measurement of effective HRM to life:

- HR has guaranteed the Chief Executive a turnover/net-required-headcount target below a certain level, combined with a staff satisfaction above a certain level. Using a variety of tools, including target motivation, job shifting, job netting, training and communication, they manage to meet the corporate staff turnover target. If they had failed, serious changes would have followed. If they had exceeded target, their bonuses would have risen;

- HR delivers a recruitment strategy to a division head who needs new IT staff. HR guarantees the strategy will work. When the strategy falls five staff short, the division head is credited by HR with the income he would have generated had the staff been found. If the strategy had exceeded expectations, HR would have been credited appropriately;

- HR performs a review of appraisal practices and bonus schemes, identifying a department where they predict future higher-than-average staff turnover. The department head agrees to follow HR's recommended actions. When the actions work better than expected, HR are credited with 50% of the better-than-projected staff turnover reduction. Had the department head not followed the recommended actions, his or her department would have been removed from HR's corporate targets - a potential embarrassment to him or her (if HR are respected) or a potential relief to him or her (if HR are interfering and ineffective);

- HR identifies that demographics in a particular country are not favouring their organisation. For most organisations this is a nice strategic observation, but for this HR unit it's a call to action. Working with the country manager they develop a pre-graduation exposure and involvement package which they sell to educational establishments, pre-clear temporary overseas workers, examine ways of outsourcing to other group functions abroad and push an automation campaign to reduce staffing requirements. The country manager supports the programme because her bottom line is credited directly from HQ based on the assessment of her HR improvement.

No Guarantees - No HR Value

The key items in the four examples above are that HR has measured what it can do, measured what it did and shared the rewards with the operation it has helped. The list of possible measurables can continue, e.g. HR and an innovative recruitment method, HR finding and pre-qualifying recruits in advance of direct business requests, HR indemnifying the organisation centrally that following proper procedures will lessen industrial tribunals, HR indemnifying a manager financially against industrial action. What makes measurement difficult in the above examples for some people is that the measures involve recognising risk. Further, risk in the above examples will be difficult to quantify in advance. On the other hand, while recognising that risk complicates measurement, the presence of risk does not invalidate measurement. Risk management is a constant factor in managers' lives, arguably the reason managers are employed and given responsibility for other people's capital is to manage risk. Subjective measures of risk by managers can be used - much traditional insurance relies on subjective measures, "experience", when statistically valid information is only partially available. An HR professional, as any professional, should be able to provide non-professionals with risk assessments and measurements, not just opinions.

There are a number of possible models for HR unit measurement. Few existing models put a strong emphasis on money, possibly because direct contribution to performance is a tough measure, as anyone who has set sales commissions knows. In practice, the first two of the following five models are common and they both typically result in a central, politically-driven HR function:

Model Measurement Pros Cons cost-centre: HR is just a corporate overhead largely political, possibly supplemented with customer satisfaction surveys or structured feedback easy to do – the organisation subsidises all HR - subject to all politics

- size set arbitrarily

- no power

– decisions made politically consultancy (profit centre): HR projects are costed as if done by an outside consultancy firm and possibly partially subsidised - organisational units' expenditure

- project appraisals

- customer satisfaction benchmarked against external consultants - people may buy to get reinforced corporate knowledge - simple measures

– utilisation for instance

- size partially set by demand - consultancy is not a core organisational competence

- people may be compelled by corporate policy to buy consultancy, or to buy at non-market rates

- difficult to remain an HRM unit rather than a consultancy business

- why shouldn't people buy from outside value-added advisor: a sometimes used HR unit, typically for complex projects measured on a portfolio sampling of projects and their relative success rates with and without group HRM’s involvement - unit size kept low - identifiable specialist expertise - self-selection of flattering projects

- too easy to avoid involvement in core organisational problems, e.g. improving customer service

- easy to become an internal Machiavelli risk management unit: charges insurance premia (e.g. to business units, sites and projects) - performance in managing group risk - ideally quantified - benchmarks against other firms and insurers - strong risk control with teeth

- helps key projects and units avoid major pitfalls

- spreads best practice

- will work throughout the organisation

– not just for mega-decisions - focused more on the negative rather than the positive

- a natural extension for finance and internal audit risk/reward unit: combines capital charge and risk management - as a venture capital fund merged with an insurer

- shareholder value enhancement - strategic advice matters

- HR Professionals have controlled power

- looks at the totality of the opportunity or risk - an emerging model - complex measurement

- not a quick fix

- need for management continuity

The biggest transition in the above models is from the third to the fourth. The risk management unit model already exists in some large corporates and is naturally progressing to the risk/reward model. The risk management unit model does couple the HR unit with the business strategy and a key reason for existence - making money; the risk/reward model even more so. Risk/reward models are used in some of the larger multi-nationals, particularly those which have evolved structured finance operations yet realise the importance of implementing sound strategic thinking. Results have been largely positive, sometimes very positive. However, some hard-won lessons show that risk/reward models require sophisticated management, need a management team with a keen eye on increasing shareholder value and must be led by a politically-astute head who knows how to say "no" to other directors through 'price' mechanisms.

Ensuring the Strategy is Met

The risk/reward model began over 150 years ago as a mutual insurance model in a number of areas such as shipping, health and trade. Interestingly, some of the first risk/reward models were based on 19th century HR issues in organisations such as the factory mutuals. These factory mutuals formed a group of 40 non-profit risk management firms in New England factories which were admired by trades unions because they strove to reduce risk and injury to workers. Today most multi-nationals and many large corporates have established risk management units, often very insurance focused, running their own internal mutuals. Recently, some of the leading corporates have moved markedly from having the risk management unit handle commerciably insurable risk, e.g. fire, theft, employer's liability, to managing less quantifiable direct business risks as well, e.g. brand damage, loss of ISO9000 group certification or contract delay. A very few have merged the risk management unit with the central capital allocation function to form risk/reward units which function as structured internal investors, fitting the management internal systems to the corporate strategy.

It is not all finance. One British corporate is looking at handing the management of Investors in People (IIP) compliance to the risk management unit. As managers in the corporate need to 'cut corners' in IIP to achieve their business targets, their 'premia' will rise and their ability to meet targets impacted appropriately - markedly for some, hardly at all for others. As managers fully comply with IIP, their premia will fall. The board sets an overall risk profile (e.g. loss of IIP will cost us 3% to 6% loss in productivity and 2% loss of turnover). The risk management unit distributes that risk around the organisation and reports back to the board, over time, on the accuracy of its distribution and assessments. Managers can make decisions about the balance of effort they put into all corporate initiatives, but have the consequences brought back to them in terms they understand - the bottom line on which they are measured. Mandatory corporate schemes attract suitably high premia, yet the corporate centre cannot over-apply 'mandatory initiatives' because the centre too can see the risk and cost effects.

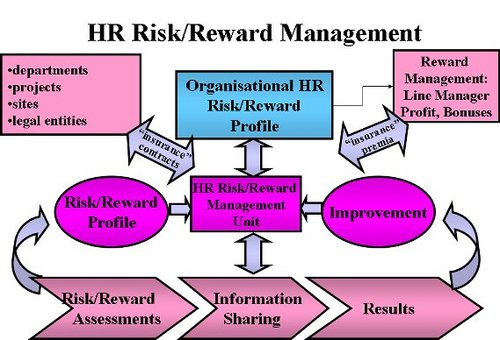

Some generic thoughts on risk/reward management can be explored in Mainelli (1999), but the following diagram attempts to show schematically how these internal mutuals, these risk/reward management units, work:

The key features of the HRM risk/reward model are a central unit which:

- works with the Board to assess the risks and rewards - threats and opportunities - in HR strategy, policies and procedures;

- receives an overall risk/reward profile from the Board in financial terms against which HRM will be measured (e.g. ROI in HRM of 500% and maximum expected HR loss of £1.2 million);

- performs assessments on key business units, e.g. departments, sites, legal entitites, projects to rate their risk and reward;

- offers managers a premium and a work programme against which the managers' bottom lines are partially insured by HRM;

- publishes assessments and results publicly in order to promote best practice throughout the organisation and to provide managers with a means to negotiate;

- works with managers when results are not up to expectation, including accompanying them to explain variances;

- works with other managers to spread successful practices;

- reports back to the Board, in financial terms, on success in overall risk reduction and reward enhancement.

HR Union

Risk/reward models strongly connect HR with the corporate strategy. They also connect HR strategies, policies and procedures with line managers - uniting managers HR adherence and decisions with bottom-line results. Risk/reward models put HR managers in the front-line being measured with their fellow managers. It is difficult to discern the longer-term alternatives to risk/reward management. The era of large corporate centres has gone. Organisations have moved to business models where the 'system' encourages appropriate behaviour in a unit, or the unit is eliminated. HR professionals need to encourage the formation of appropriate HR systems within the organisation that demonstrably prove the HR link to the business strategy - uniting HR with shareholder value. In summary, we believe that:

- HR needs to enforce its own measurement discipline in order to move from a corporate overhead to a value-adding strategic partner;

- Proactive and reactive are not antithetical, nor is either necessarily more strategic;

- HR is involved in the first of the three strategic phases, planning, but needs more structured models for implementation and evaluation;

- Risk/reward models are emerging for the effective implementation and evaluation of many central corporate functions and are beginning to touch on HR areas;

- Risk/reward models effectively meld the proactive and the reactive, uniting them with the business strategy.

HR units will never have an easy ride. Few operational directors want anyone second-guessing their decisions. At the same time, few HR units want to spend their time devising unused procedures or exhausting strategies to justify other people's gut feelings. Unless the HR unit wishes to remain the Chief Executive's lapdog, it must stand up and state how it proposes to measure its own success in comparison with the rest of the organisation. Publicising a clear measure of success, and meeting it, attracts political power in its own right. If there is a corporate political strategy lesson for HR units, it must be to agree with the organisation a rigorous way of measuring their own contribution to corporate success. If there is a lesson for head office contemplating the future of HRM, it must be to dispel Hussey's fifth Myth, "Evaluation and performance measures are too difficult and expensive for HRM activities, and HRM does not need to be subject to such disciplines."

References

David Hussey, Business Driven Human Resource Management. John Wiley & Sons, 1996 [enjoy Myths 3, 4 and 7].

Michael Mainelli, "Organisational Enhancement: Viable Risk Management Systems" (2 parts), Kluwer Handbook of Risk Management, Issues 27&28, pages 6-8/2-4, 16 April 1999, 12 May 1999, Kluwer Publishing.

Michael Mainelli is a Director Z/Yen Limited, a former Vice-Chairman of The Strategic Planning Society and a former Director of the Defence Evaluation and Research Agency. Ian Harris is a Director of Z/Yen Limited whose HRM work with several leading organisations, e.g. Ideal Hardware, is recognised as leading the field.

Z/Yen Limited is a risk/reward management firm which uses risk analysis and reward enhancement techniques to improve organisational performance. Z/Yen has advised many organisations on the role, structure and measurement of HRM units and risk/reward units.

[A version of this article originally appeared as "Ensuring People Risks, Rewarding HRM: Proactive and Reactive Link of HRM to Business Strategy", Journal of Professional HRM, Croner (March 2000) pages 3-8.]

http://www.zyen.com/143