Banking On Confidence: Rethinking Audits Of Financial Institutions

By

Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Securities & Investment Review, Securities & Investment Institute (September 2011), pages 22-23.

After the financial crisis we realised that the balance sheet and going concern statements of many of our major financial institutions proved wrong. The ‘Credit Scrunch’ of 2007 was a systemic failure. Interactions between elements of the system (banks, rating agencies, regulators, governments, financial instruments, auditors, etc.) mattered more than the specific behaviour of a particular actor. If you believe the crisis was an apocalypse or foreshadows an apocalypse, then you should be considering fundamental redesigns in numerous areas. How might we redesign auditing?

Auditing and accounting have been subject to much criticism over the past two decades. Criticism perhaps reached a peak in the early 2000’s after a series of telecommunications and internet failures, coupled with Enron’s collapse. Another peak of criticism followed the financial crises of 2007 to 2008. These criticisms are many and varied – audit firm market concentration, lack of independence, principal-agent problems, lack of indemnity, relationships with regulators, mark-to-market rules. Rarely, if at all, does criticism seem to question the basis of audit and accounting in terms of measurement science.

People who move from science to accounting are stunned to find that auditors do not practice measurement science. Scientific measurement specifies accuracy and precision. Accuracy - how closely a stated value is to the actual value. Precision - how likely repeated measurements will produce the same results. A measurement system can be accurate but not precise, precise but not accurate, neither, or both. If your bathroom scale contains a systematic error, then increasing sample size by weighing yourself more often increases precision but not accuracy. If your bathroom scale is very accurate but your past and future weight fluctuate wildly, today’s spurious accuracy is not a good guide to your weight, e.g. for safety purposes.

Scientists view measurement as a process that produces a range. Scientists express a measurement as X, with a surrounding interval. There is a big difference between point estimation and interval estimation. Auditors provide point estimates, scientists intervals. For example, physical scientists report X ± Y. Social scientists report interval estimates for an election poll and state how confident they are in that the actual value resides in the interval. Statistical terms, such as mean, mode, median, deviation, or skew, are common terms to describe a measurement distribution’s ‘look and feel’. The key point is that scientists are trying to express characteristics of a distribution, not a single point. Finance should be no different.

‘Confidence Accounting’ is a term for using distributions rather than discrete values in auditing and accounting. The term was coined by Long Finance (www.longfinance.net) proponents as part of a shift to interval estimates and confidence levels, making auditing and accounting more closely resemble other measurement sciences. In a world of Confidence Accounting, the end results of audits would be presentations of distributions for major entries in the profit & loss, balance sheet and cashflow statements. The value of freehold land in a balance sheet might be stated as an interval, £150,000,000 ± 45,000,000, perhaps recognising a wide range of interesting properties and the illiquidity of property holdings. Next to each value would be confirmation of the confidence level, e.g. 95% confidence that another audit would have produced a value within that range. Finally, there would be a picture, a histogram of the distribution, so people can see the shape of things. The proposed benefits of Confidence Accounting include a fairer representation of financial results, reduced footnotes, measurable audit quality and a mitigation of mark-to-market perturbations.

To move discussion further along it would help to be able to show a worked example, i.e. a pro forma set of accounts based on Confidence Accounting, so in April 2011, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) commissioned Z/Yen Group Limited (Z/Yen) to provide a short worked example of how a set of audited accounts prepared under Confidence Accounting might look, and to promote the paper via Long Finance for discussion. CISI was pleased to support this work, and ran an afternoon seminar on 11 May to discuss the draft worked example.

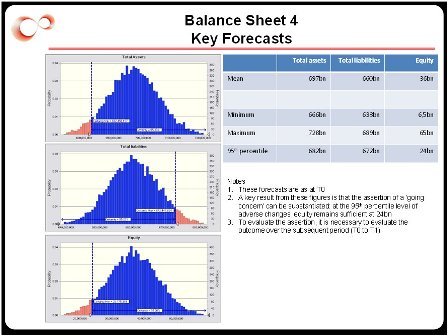

The worked example takes the form of a presentation by the finance director of a hypothetical UK bank, loosely based on an actual major institution. The example concentrates on the key line items in the balance sheet and income statement, and draws on disclosures in the annual reports over a five year period. The example attempts to illustrate the key assumptions that are required to produce a pro forma set of accounts based on Confidence Accounting including a graphical presentation of the results. A sample slide from the presentation is reproduced below (Slide: Balance Sheet 4), where the finance director works out whether or not the bank retains sufficient equity:

The finance director points out that the mean value of equity at the balance sheet date is £36bn, with a minimum of £6.5bn and a maximum of £65bn, with 95% confidence the value of equity is at least £24bn. The 95th percentile value supports a ‘going concern’ assertion (assuming that £24bn is sufficient for regulatory requirements). If the state of the world doesn’t change, the realised value of the balance sheet should be no more than £(36-24=) £12bn worse than the mean. If the income over a subsequent period would fall £12bn short, and cannot be explained by either a change in the fundamental business climate, a very substantial change in the business model and exposures, or a very large intra-period event, then the quality of the balance sheet (and audit) must be called into question.

The worked example concludes that Confidence Accounting can be applied to banks and results in a fairer representation of financial results. Further, it provides a basis for beginning to reconcile balance sheet valuation and market value, and certainly highlights the need for clarity between uncertainty over valuation during the period of going concern versus risk about changes in the state of the economic climate. One big benefit of Confidence Accounting is that it reduces the size and complexity of annual reports, in the case of Royal Bank of Scotland probably by between 30 and 60 pages.

Finally, under Confidence Accounting, external assessors could evaluate auditors’ performance. Any audit firm will have a number of client restatements or failures over, say, a decade. If failures are within confidence levels, then we have a good, or even too prudent, auditor. If not, perhaps a sloppy, or statistically unusual, auditor. Markets will price the value of higher confidence levels, and quality auditors will be able to value work on better disclosure appropriately. Redesigning the edifice of audit begins with rethinking. Moves towards Confidence Accounting will not happen overnight, but CISI is helping with rethinking audit.

Professor Michael Mainelli, PhD FCCA FCSI, originally undertook aerospace and computing research, followed by seven years as a partner in a large international accountancy practice before a spell as Corporate Development Director of Europe’s largest R&D organisation, the UK’s Defence Evaluation and Research Agency, and becoming a director of Z/Yen, the City of London’s leading commercial think-tank (michael_mainelli@zyen.com). Michael is Emeritus Professor of Commerce at Gresham College (www.gresham.ac.uk) and a Visiting Professor at the London School of Economics & Political Science.

[This article was republished as "Banking on Confidence: Rethinking Audits of Financial Institutions" Corporate Governance and Sustainability Challenges (October 2011).]

[An edited version of this article appeared as "Accounting for Confidence" Securities and Investment Review (September 2011), pages 22-23.]