All Or Nothing: Product Control Goes Global Or Local

By

Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Balance Sheet, The Michael Mainelli Column, Volume 12, Number 4, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pages 42-44.

Dr. Michael Mainelli, The Z/Yen Group

Front, Back and Sideways

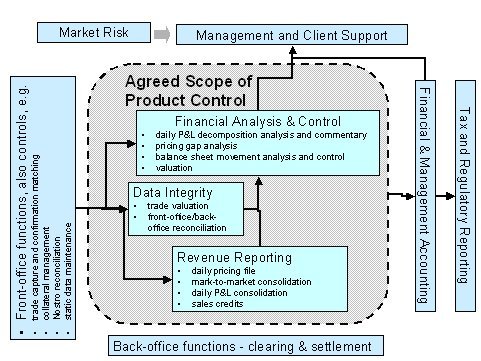

Between the front and back offices of investment banks lie the “middle offices”. Middle office functions vary from bank to bank, as does the importance and size of the middle office, but typically include administration and support for the front office. Increasingly, the middle office is home to control functions, such as product control and risk management, that need close liaison with the front office in order to determine the accuracy of profit and loss figures or risk exposures initially provided by the front office. Product control typically provides independent price verification, position reconciliation and daily profit validation.

Investment banks have a variety of different product control or product accounting structures. Product control ranges from reporting to a single, global product control head through to being combined with other middle office functions or allocated to product lines. Research about product control is sparse. While functions defined as ‘product control’ all exist within investment banks, the grouping of functions varies widely.

“We want a standardised P&L process globally. We’re not there yet, but definitely moving towards it.” – Global COO Product Control

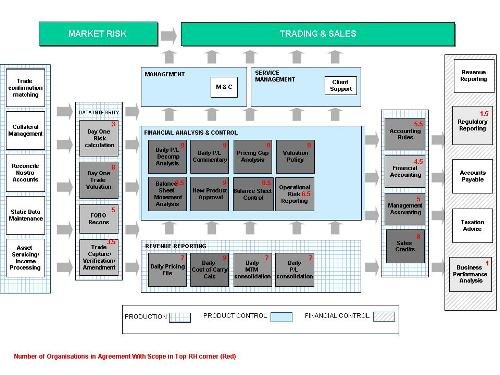

During 2003, Z/Yen conducted a survey of product control functions within 9 investment banks. The survey consisted of 20 structured interviews with the heads of product control at a global or European level whose departments were called product control, business unit/area controlling or middle office, as well as an additional 6 other interviews with relevant experts.

The 2003 survey found a wide variety of organisational approaches to product control:

- highly segregated product control, with an emphasis on ‘control’, reporting to a senior head (vertical) and then through the finance function, sometimes via internal audit – 4 of the 9 investment banks.

- operationally integrated product control, with an emphasis on trade support, reporting to an operations head or head of finance within operations, as opposed to reporting through the finance function – 2 of the 9 investment banks;

- mixed, 3 of the 9 investment banks, either segregated with trade support roles (2 of the 9) or operational but largely separate at lower levels (1 of the 9)

“There are three potential organisation models of Product Control and Market Risk. 1) Have all 4 functions separate, Daily P&L, Price Verification, Accounting and Market Risk. 2) Have Market Risk and P&L Production together and Price Verification and Accounting Together. 3) Have Daily P&L, Prices and Accounting together with Market Risk separate.” - Head of Capital Markets Product Control

Like It Is

Despite the variety of organisational structures, there was relative unanimity on the ‘core’ functions of product control and things which were definitely outside product control (see Agreed Scope of Product Control diagram). Ratios of product control staff to front-office staff ranged from 1:1 in areas such as derivatives to 1:20 for vanilla and exchange-traded products. Most organisations did not perform daily balance sheet calculations. Month-ends are a ‘bump’ for product control, requiring extra staff overtime for periods extending from 2 to 8 days, and typically with overtime of between 2 and 5 hours. Organisations had a variety of ways of handling 24 hour reporting, either living with different time zone data or systems of ‘flash’ reports with later ‘finals’ and variance explanations. A number of banks seemed to be trying to increase the skills of staff, e.g. bringing in more technical accounting expertise, while reducing the drudge through automation.

Operationally integrated organisations judged product control largely by its ability to satisfy front-office and other operational department expectations. Decisions tended to be pragmatic – “what gets the job done”. Segregated organisations were clear about product control principles and had the clearest roles with clear ownership of reconciliation systems. Segregated organisations seemed to be more efficient, although efficiency observations need to be treated with caution as in mixed organisations product control tends to be ‘doing’ more, i.e. control functions with trade support. There was little correlation between the amount of proprietary trading and structure. More than half of participants were looking seriously at major restructuring of product control with some segregated organisations looking at moving operational and vice versa.

“If you organise horizontally then your main concern is in supporting the business, if you organise vertically then you are more concerned with controlling the business.” - Head of Equity Product Control

“You can be organised functionally or business aligned, both structures have their benefits and in our opinion you should cycle between the two, probably every two to three years.” - Head of Fixed Income Product Control

Everyone had a strong emphasis on product control management by headcount. Few organisations manage product control operations with Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Only one organisation was managing product control based on quality measures. Bonuses for product control staff seem to be largely discretionary, rather than based on quantitative measures. Measuring product control’s success was widely seen as difficult, although everyone seemed to have given this much thought, for instance the number of late P&L’s, the number of unexplained items, reconciliation breaks, price testing differences, etc. Organisations did not feel that cost was strongly related to trading volumes or currencies or locations, but did feel that costs were driven by some factors almost wholly outside their control, such as the number of product types traded, the complexity of products (especially derivatives), the number of legal entities or the number of regulators.

There seemed to be great interest in attempting to benchmark product control by some common numerators such as headcount or cost, if it were possible to agree on some common denominators, but there seemed to be problems with most suggestions for a denominator, e.g., cost or headcount per book, per P&L, per trader, per unit revenue, per transaction, per system interface or per legal entity? According to one interviewee - “if you want to reduce headcount, then reduce the number of businesses you are in.” Organisations did feel that they could reduce costs if they could automate P&L production and decomposition, otherwise most savings would be “merely better management”. Re-engineering product control ultimately depends on automation.

Product control systems were highly customised or bespoke, although naturally popular database packages or semi-customised general ledger packages underlay them. Some participants felt that an efficient product control system provided competitive edge. Technology had produced the most savings in product control when it either increased automation, particularly having a global product control reporting and decomposition system, or increased the use of straight through processing (STP) - “I don’t see how anyone can make real reductions in product control costs without a global product control system.”

Get a Grip on the Big Picture Details

The stepping stones to successful product control appear to be:

- clear decisions on segregated versus operational model: the clearer the choice of model, the less likely product control is going to be divided both in operations but also loyalties;

- commitment to lines of business: product control performs better where the business realises that essential product control is a significant, unavoidable fixed cost for operating a business line rather than something that can be skimped on at early stages. Product control cost savings are best realised by exiting a business line – volume reductions have much less effect;

- clear responsibility and reporting lines: shared functions, e.g. a bit of P&L production, as well as unclear reporting lines, e.g. head of operations but dotted lines to X and Y, impede effective performance of product control;

- standardisation: leading product control functions emphasise the importance of a single approach to P&L production, standardised processes, standardised relationships with trading and operations colleagues, and increasing the inter-operability of product control staff. Standardisation leads to simplification;

- automation: the biggest differentiator among participants was the presence (or absence) of a global product control system producing all P&Ls in a standardised manner. With a global product control system, inter-operability was high, product control could do more advisory analysis and efficiencies were greatly increased.

“Previously only at an extremely senior level of management did the full life cycle from trade capture through to reporting come under one umbrella, this has now moved down to VP level within the Bank. This has led to a significant improvement in communication and a large decrease in duplication of effort.” - Global Head of Equity Product Control

Longer-term however, the structure of product control may be determined more by outsiders than management. In the future, regulatory trends indicate that product control is likely to be split decisively between the front-office support functions and imposed controls, typically those undertaken within risk management or internal audit. If this is the case, then the views of one interviewee ring true - “We don’t see ourselves as Trade Support; our first and foremost role is as Controllers; Product Control’s decision is final.” Whatever the final outcome, the message is that clarity matters – either product control is a global control function or it is a local trade support function. Where a clear decision is made, performance is enhanced.

Michael Mainelli, FCCA MIS, originally did aerospace and computing followed with seven years as a partner in a large international accountancy practice before a spell as Corporate Development Director of Europe’s largest R&D organisation, the UK’s Defence Evaluation and Research Agency, and becoming a director of Z/Yen (Michael_Mainelli@zyen.com).

Michael’s humorous risk/reward management novel, “Clean Business Cuisine: Now and Z/Yen”, written with Ian Harris, was published in 2000; it was a Sunday Times Book of the Week; Accountancy Age described it as “surprisingly funny considering it is written by a couple of accountants”.

Z/Yen Limited is a risk/reward management firm helping organisations make better choices. Z/Yen undertakes strategy, finance, systems, marketing and intelligence projects in a wide variety of fields, such as developing an award-winning risk/reward prediction engine, helping a global charity win a good governance award or benchmarking transaction costs across global investment banks.

[An edited version of this article first appeared as "All or Nothing: Product Control Goes Global or Local", Balance Sheet, The Michael Mainelli Column, Volume 12, Number 4, Emerald Group Publishing Limited (2004) pages 42-44.]