Chapter 4: Knowledge Management

Chapter objectives

In this chapter we shall:

- Try to define knowledge management.

- Explain why knowledge management initiatives tend to be difficult to get off the ground and then often drift once they do.

- Provide some useful tips and pointers for successful knowledge management initiatives.

- Illustrate the thinking.

What is knowledge management

“Knowledge management” is currently a fashionable organisational term. The potential rewards are enormous: cultural cohesion, harnessing know how, sharing skills and experiences, getting tangible gain from your intellectual capital, the list is nearly endless.

As a result, providers of a myriad of products and services are rushing to describe their wares as “knowledge management”. This variety of claimants includes, but is not restricted to, software producers, change management consultancies, operational process managers, marketing and communications advisors, information technology managers, business strategists and human resources practitioners. Many such claims have validity. While it might be fun to watch internal and external providers competing for the “knowledge high ground”, the diversity generates some practical issues and risks for not-for-profit organisations that actually want to get things done, especially in terms of the definition and ownership of initiatives.

One can sympathise up to a point with organisations struggling to define their knowledge management initiatives. After all, many knowledge management initiatives are born from a desire to “find out what knowledge we have out there” or to “break down traditional barriers (e.g. regional, departmental) which prevent us from sharing our knowledge”. For example, a large research and development organisation, which described the establishment of its corporate intranet as a knowledge management initiative, was disappointed when the initiative failed to take off. The problem was not the medium (intranets are often very effective media for knowledge management initiatives) but the message (there was little or no guidance to staff on what to do with the medium). This "initiative" was adrift more or less from the moment it started.

Contrast the above example with a distribution client of ours which established its knowledge management initiative, also using an intranet, around a handful of well defined areas (skills and experience logging, team performance, other initiatives bulletins/discussion) and provided incentives for timely and accurate update of the information. The distribution company’s initiative took off at breakneck speed and the value of the knowledge generated on their corporate intranet is enormous.

Knowledge management initiatives, like all projects, benefit enormously from having a clearly defined scope and objectives. Successful initiatives will of course “morph” and expand through demand, but that expansion should also be clearly defined and should have tangible objectives.

Managing expectations

Knowledge management initiatives often deliver significant benefits yet fail to meet expectations. Often this is because the initiative was “sold” (internally or externally) as a panacea and couldn’t possibly succeed in meeting the expectations the launch generated. There are several risks arising from unrealistic expectations. Perceived failure despite material successes is a substantial risk. Perhaps more severe (e.g. costly and time wasting) is the risk that the initiative becomes over-engineered in a futile attempt to meet unrealistic expectations.

Case Example: A Result of Unrealistic Expectations

A large international not-for-profit organisation asked the current authors to review its knowledge management initiative and explain why it was failing to meet almost everyone’s expectations. The programme of work had been “sold” to staff as a toolkit to help them all to manage just about everything the organisation did. In order to try and meet this unrealistic goal, the initiative team had tried to tag on all manner of functions. This organisation had even written its own mini spreadsheet for costing its specific projects and its own mini project management tool for managing its programme of good works. Needless to say, these “knowledge management initiative” modules fell short of expectations, were less effective (and much more expensive) than standard software packages and had little (if anything) to do with sharing information and knowledge.

Painful though it might have seemed to this organisation, the sensible way forward was to scale back the scope of the initiative to the core (which was useful, valuable and achievable). This approach enabled the organisation to deliver real benefit to its staff and stakeholders through a scaled down system that people could understand and use easily. The benefits from information and knowledge sharing could then flow.

Ownership of knowledge management initiatives

Most departments or divisions in a sizeable organisation can stake their claim to knowledge management. “Knowledge management is all about: [information technology], [human resources], [strategy & planning], [service delivery], [fundraising], [communications] (delete where inapplicable)”. When initiatives are well defined and are clearly focussed wholly or primarily in one area, clarity regarding ownership of the initiative is relatively easy to achieve. Where initiatives manifestly cut across existing organisational boundaries (often harder to define but often more effective than departmental initiatives), clarity of ownership can be harder. Many larger organisations, seeing knowledge management as increasingly important and “boundary shifting”, have established knowledge directorates specifically to own and drive their knowledge management initiatives. Others govern their knowledge management initiatives through cross-departmental boards and/or expert panels (this form of ownership is especially common in cross-organisational knowledge management initiatives).

There are no right and wrong answers here. The distribution company referred to above, which focussed its first knowledge management initiative on skills and performance drove the initiative through its human resources function. The less focussed R&D organisation at first ran its initiative out of the information technology department. There is an important distinction which frequently gets missed; the distinction between ownership of knowledge management initiatives, ownership of the information within knowledge management initiatives and ownership of the infrastructure (often technological) through which the information is delivered. Each aspect requires clarity of ownership and co-ordination. The thinking here is analogous with the thinking in chapter 3.

Measuring success

Even when the initiative is well defined, expectations are reasonable and ownership of various aspects of the initiative clearly set out, it is often still fiendishly hard to set tangible success measures. Where success is largely intangible and hard to measure there are two polar views: “don’t bother” or “try harder”. The authors subscribe (within reason) to the latter.

As a minimum, it should be possible to set tangible milestones on the initiative itself and measure whether or not the activities of the initiative are being achieved on time and on budget without reducing scope. It is usually easy to set some targets and measure information volumes and usage statistics. Such output measures don’t necessarily reflect effectiveness, but some measurement is much better than none. Further, in environments where usage is not compulsory or necessary, usage statistics are reflecting a form of market forces which is surely at least an indirect measure of effectiveness. If staff are voluntarily “hitting” the knowledge management system on average eight times a day (as in the case of the distribution company), staff must feel that this is a valuable source for their work. To be sure, usage is only one factor - some elements will be little used but highly effective and valuable while other elements will be used often but add little.

Further, it is always possible to measure perceived value and satisfaction amongst the people involved in the knowledge management initiative, both providers (the initiative team) and users. Successful knowledge management initiatives often emerge from iterative processes. Structured feedback should provide tangible measures over time and provide vital input into the process of continuously improving the knowledge management initiative to minimise the risks and maximise the rewards.

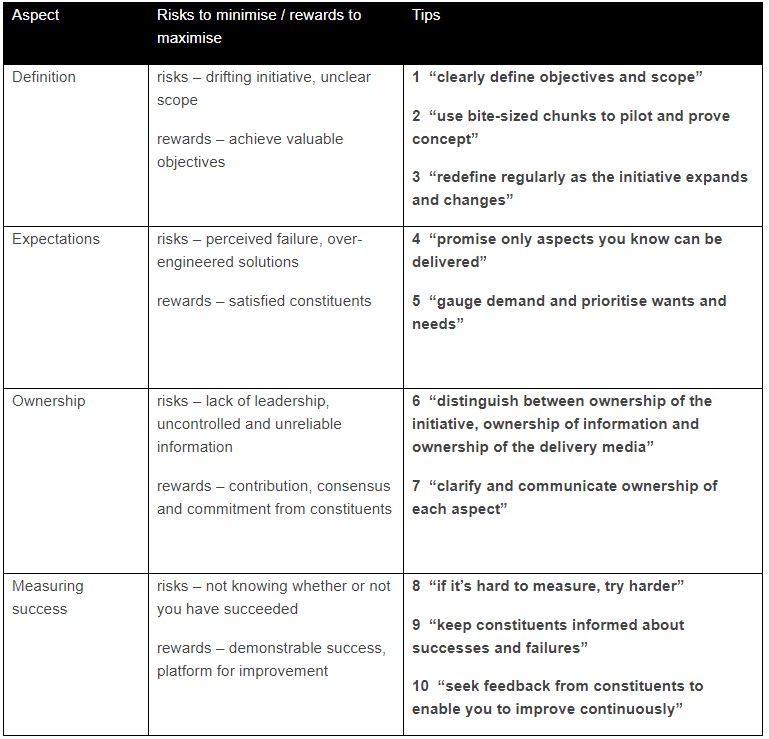

The following table sets out ten top tips for minimising the risks and maximising the rewards from knowledge management initiatives.

Table 4.1 Ten Tips For Achieving Success With Knowledge Management Initiatives

Summary

- Almost anything and everything might be labelled as knowledge management these days, so ensure that there is clear and sensible scope and well defined objectives to your knowledge management initiative.

- Don't promise more than you can deliver and clarify who owns the knowledge management initiative.

- Ensure that you are measuring the success of the initiative, partly to justify your use of resources on this initiative and partly to ensure that you are continuously improving your knowledge management.