Chapter 3: Governance

Chapter objectives

In this chapter we shall:

- Explain the distinction between information systems and IT infrastructure, why it is important and how to define both.

- Discuss issues relating to paying for IT, including authorisation, cost allocations and capital versus expenditure.

- Raise the matter of co-ordinating the use of IT, including setting and controlling IT standards.

- Provide some examples of how not-for-profit organisations deal with the governance of their information systems and IT infrastructure.

- Encourage not-for-profit organisations to try to value the benefits of IT.

- Borrow valuation techniques from the world of audit and basic finance in order to help value those benefits.

- Categorise the risks and rewards of information and knowledge management.

Information systems and IT infrastructure

There is an important distinction between information systems and IT infrastructure. Information systems are the applications through which we record, process and present data in the form of information. IT infrastructure is the collection of mechanisms that receive, store and transmit data to enable the information systems. In summary; information systems are the user programs, IT infrastructure is the machines, networks and enabling software. A domestic analogy: information systems are the equivalent of domestic electrical appliances whereas IT infrastructure is the equivalent of the electrical cabling.

There are several reasons why the distinction between information systems and IT infrastructure is important:

- The skills required to manage information systems are different from the skills needed to manage IT infrastructure.

- It usually makes sense for different parts of an organisation to manage or 'own' the systems and the infrastructure. For example, specific departments often 'own' the systems (e.g. fundraising department “own” the fundraising system, finance 'own' the accounting system whereas a support services department 'owns' the IT infrastructure).

- Processes within systems and the data within systems should all have clear ownership. For example, systems that cover more than one department (often a recipe for unclear ownership) should at least have clear ownership of processes and data identifiable down to departments, projects, units or whatever.

- Governance mechanisms for investment and ongoing expenditure on information technology is likely to differ between spend on information systems (which is usually attributable to one or two functions or departments) and spend on IT infrastructure (which is essentially a shared resource across the whole organisation).

- The distinction has an impact on who pays (or should pay) for the particular bit of IT (see 'Who pays?', below)and who takes responsibility for co-ordination (see 'Co-ordinantion aspects of governance', below).

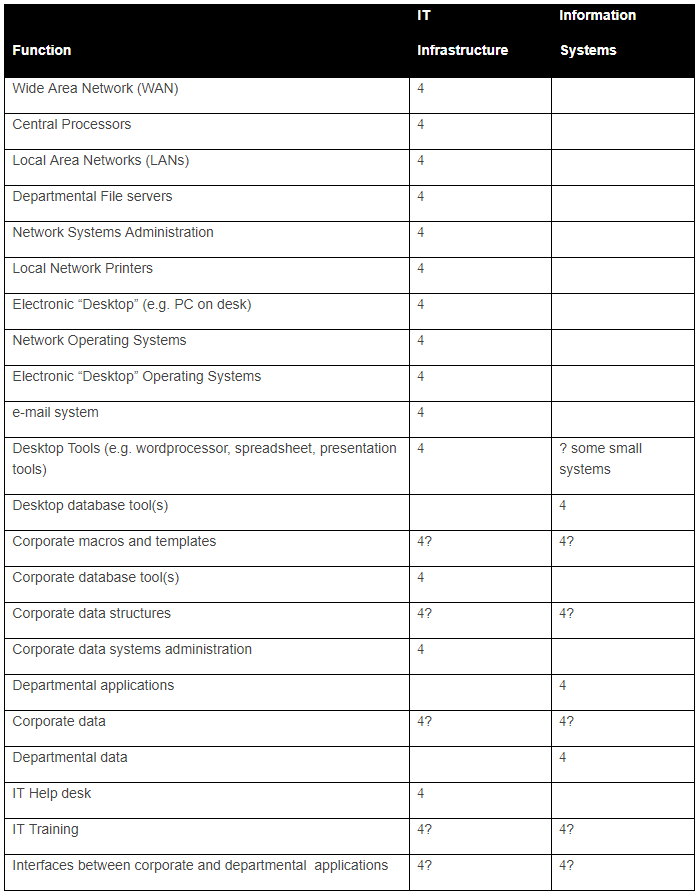

Distinguishing between information systems and IT infrastructure

Table 3.1 should help you to distinguish between information systems and IT structure, as well as highlight the main 'grey areas'. The trick is to ensure that your organisation has clear definitions and allocates management, ownership and governance sensibly and unambiguously.

Table 3.1 Information Systems and IT Infrastructure

Who Pays?

Once you have sorted out the above relationships the answer to the question 'who pays?' should be simple - the owner. If you are spending money on a particular application, the user department(s) involved should pick up the tab.

Many not-for-profit organisations need to consider the extent to which funding partners should be expected to share the cost of IT. This is especially important for service providing organisations where IT costs can form a substantial proportion of the costs of projects. It is a fairly common mistake to minimise or avoid cost allocation, only to find that IT costs (perhaps erroneously deemed to be central) are escalating rapidly with no corresponding source of funding to maintain services.

The authorisation for spending should normally follow the same rules as you have for other items in your organisation. IT expenditure is prone to 'fudging' between capital and revenue definitions, so your rules should be simple and clear.

Case Example: Capital or Expenditure?

At Z/Yen, for example, we treat new IT equipment (e.g. portable computers, servers, routers) as capital to be written off over three years. Operating systems software (e.g. Windows 2000) is deemed to be part of the equipment for the purposes of capitalising, budgeting, authorisation and accounting policy. Applications software (e.g. Office 2000, Quickbooks, Crystal Ball) and accessories (e.g. portable computer carry cases, modems, removable drives)are treated as expenditure and written off in the year the expenditure is incurred. However, we could just as easily capitalise applications software or treat operating systems software as expenditure. Similarly, we deem anti virus software and e-mail software upgrades to be applications and therefore expenditure, but we could deem them to be operating systems and therefore capital spend.

There are no right answers and few wrong answers to the question of what you should treat as capital and what you should treat as expenditure. For example many organisations choose to capitalise the cost of their IT application systems.

If you are recharging IT costs to user departments, you should consider whether this recharge is simply an allocation of budgets and costs or a genuine attempt to provide user departments with choices. For example, should the department spend the money on IT rather than on other things. Should the organisation procure IT centrally or allow decentralised procurement. This leads to the thorny issue of co-ordination.

Co-ordination aspects of governance

There is a paradox in the concept of user choice. In principle, you want users to have maximum freedom of choice in systems and structure. In practice, if you allow everyone to do their own thing you'll get a proliferation of incompatible systems and equipment which can quickly become uncontrollable and unaffordable - and end up restricting users' choice.

Whoever is responsible for the IT infrastructure should also have a clear responsibility to co-ordinate IT standards within the organisation. This is not a 'just say no' responsibility, but a genuine and sometimes difficult role to try and resolve the paradox of choice versus standards. Similarly, in organisations that use standard application systems in multiple locations, whoever is responsible for the application system should co-ordinate those software standards.

Standard and non-standard software

Here are some guidelines on the use of standard and non-standard software:

- where both the standard application and an alternative solution are able to meet the need, you should apply the principle of Occam's razor to the problem and choose the solution which is simplest to manage (which would normally be the standard application).

- an alternative solution to the standard application should only be accepted if there is a significant requirement which cannot be met by the standard application. The burden of proof should be upon the proposer of the alternative to demonstrate that the standard application is inadequate, as the cost and resource implications where alternative solutions are used are considerable. For example, it should not be sufficient that an alternative solution is a little easier or more convenient for one or two individuals. The "Common Good" within the organisation should take precedence.

- if an alternative solution is chosen, data from that alternative solution should be available in the standard format to enable the consolidation, aggregation and comparison of information across the organisation.

- in order to evaluate the use of an alternative solution, the full cost to both the user department/project/unit and the cost to the organisation as a whole over the life of the implementation should be evaluated. The department/project/unit should demonstrate that the benefits of the proposed alternative solution outweigh those total costs.

- where a project is a joint venture with one or more other parties, the organisation might well encounter situations where more than one organisation wishes the information systems to follow its standards. In such a situation, the organisation should negotiate for the use of its standard application. Should an alternative system be chosen for joint work, the organisation should seek appropriate financial compensation within the venture to enable the organisation to meet its own information needs as well as those of the venture and to cover any additional costs and effort the department/project/unit and the organisation as a whole will bear as a result of such a decision.

- truly single user applications, e.g. special software for one person working alone, can be viewed as a pilot.

- in other circumstances, the use of non-standard software should be prohibited, in line with the organisation's general policies on the use of non-standard software and hardware.

Examples of structuring for IT governance

Co-ordinating structures should reflect the ownership and relationships between information systems and IT infrastructure. In larger not-for-profit organisations this is likely to involve several groups. For smaller and medium-sized not-for-profit organisations, this will probably involve a fairly simple and occasional (usually at budgeting time) liaison group to ensure that those responsible for IT infrastructure have the budget and capability to provide the IT infrastructure needed for proposed information systems changes.

Case Example Barnardo's IT Governance Structure

At Barnardo’s, IT governance is vested essentially with three groups:

- a forward looking IT strategy group (including some representatives from industry) to ensure that there is appropriate long term planning for IT infrastructure to meet likely demand for information systems.

- a group of senior people from user departments primarily responsible for prioritising information systems requests and co-ordinating (i.e. en

suring that there is appropriate liaison between) new information systems projects. - a user group to ensure that the user voice is heard. In large organisations (Barnardo’s employs several thousand people) it is impractical to consult everyone on IT matters, so a representative body is appropriate.

Ian Theodoreson, Director of Finance and Corporate Services at Barnardo's, comments "even within the clear division of roles between information systems and IT infrastructure there is a dilemma. How can the project leader in any one of Barnardo's 250 project sites around the country really feel as if they 'own' the applications? Someone has to make the decision to go ahead and spend often considerable sums of money, and this decision cannot be taken on the basis of consensus opinion. The balancing factor therefore has to be the establishment of a clearly focused user group, drawing membership from across the organisation, who can identify the issues and needs that are arising and who can moderate initiatives that are emanating from the centre".

At a medium-sized not-for-profit organisation such as BEN (see part 6), IT governance is essentially vested with the directors. In addition, a group of staff from user departments meet a few times a year to co-ordinate IT activity and ensure that an appropriate level of service is maintained.

At small not-for-profit organisations, IT governance is likely to be covered by the executive(s) on a more ad hoc basis, but the above principles should nevertheless apply.

The cost of everything and the value of nothing

Governance of IT can be seen as four main areas:

- Agreeing who owns IT.

- Agreeing who pays for IT.

- Co-ordinating IT.

- Valuing IT.

We have discussed ownership, payment and co-ordination of IT, but not yet valuing it. There are many derogatory expressions about people who know the cost of everything and the value of nothing. Sadly, IT is an area where this expression is often true; many not-for-profit organisations put a great deal of effort into estimating the cost of IT projects and trying to manage those costs, but few try to value the benefits they are seeking from IT. If your organisation falls into this category, you are probably missing a trick or two.

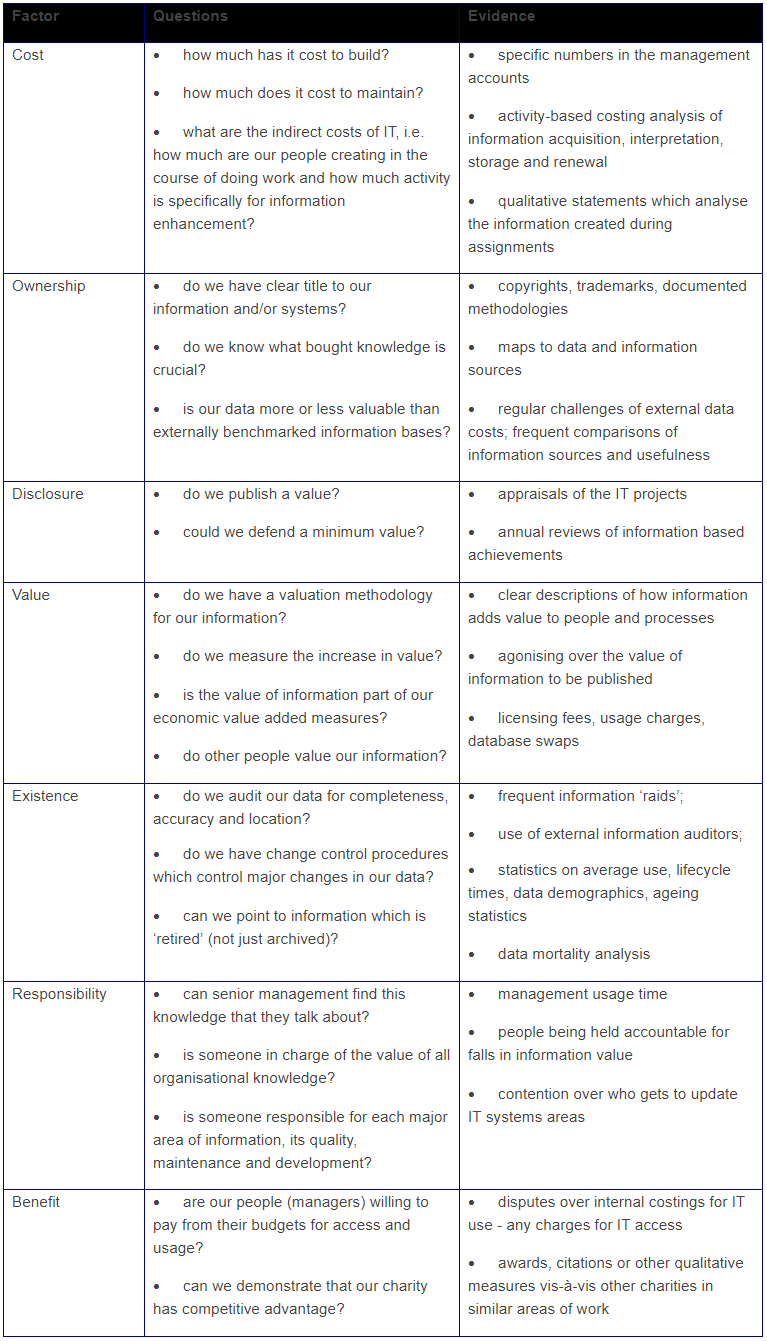

Understanding the value of IT

Often not-for-profit organisations pay lip service to phrases such as 'information is an asset' and 'the benefits of information'. To move away from lip service, in other words really to try to understand value of IT, think of the audit as an analogy for valuing IT. For any significant asset, an auditor expects seven typical pieces of evidence:

- Accurate understanding of the Cost of the asset.

- Confirmation of Ownership of the asset.

- Some Disclosure of the importance of the asset.

- Ability to confirm the Value of the asset.

- Evidence of the Existence of the asset.

- Clear lines of Responsibility for the asset.

- Measurable Benefit from the asset.

The surreal, but snappy, phrase "COD-VERB" is already catching on as a mnemonic device. Without all of the above, phrases such as 'information as an asset' or 'knowledge management' are just fluff sitting on top of some new technology. Meeting the above tests should be a goal for most not-for-profit organisations when considering applying funds to IT projects. Examining each of the seven factors in turn, we can see how leading organisations are starting to put weight behind the concept of knowledge value. The following table proposes some tests for each factor.

Table 3.2 COD-VERB Table

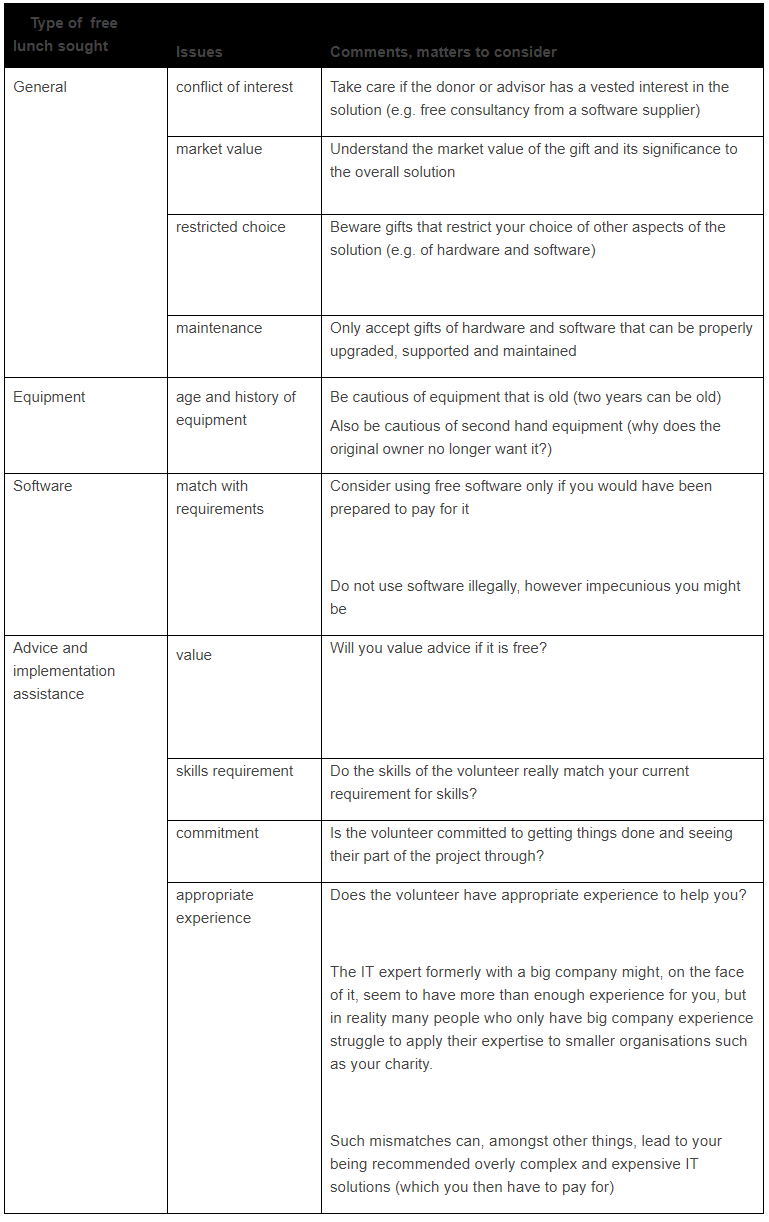

There's no such thing as a free lunch

You hardly need to be told that not-for-profit organisations often lack some of the resources (skills and/or money) required to plan, implement and evaluate a desired or needed IT solution. They often find themselves in the (seemingly fortunate) position of being offered some voluntary help with the IT project which may be in the form of goods (equipment), services (advice, skills) or both. Such help may seem like manna from heaven but it might just be a poisoned chalice. Strangely, commercial organisations are rarely offered voluntary help in this way.

This is not to say that you should never accept gifts of IT equipment and services, indeed some not-for-profits have done remarkable things as a result of gifts in kind (e.g. the Youthnet Case Study in part 6). However, you should examine the situation very carefully before accepting a gift which might not be appropriate for you. The table below raises some of the issues not-for-profit organisations should consider when considering accepting the types of voluntary help that are commonly offered.

The key thing to consider is the value you will get from the project you are undertaking. Very often, however, not-for-profit organisations undertake projects needlessly in order to take advantage of a "gift", ignoring the hidden costs involved in any IT project, such as effort, upgrades to peripheral equipment etc. Also, organisations often accept gifts without realising that there are hidden costs and risks associated with the gift itself which nullify or even outweigh the value of the gift. Gifts of old equipment frequently fall into this category. If a gift directly supports a project which you had intended to pay for in the absence of the gift and that gift does not generate hidden costs or risks that outweigh the value of the gift, then the gift might be a bonus for you. In our experience, such gifts are rare.

TABLE 3.3 No Such Thing as a Free Lunch Table

The economics of valuation

Valuation binds all seven factors of asset management. Without value, assets are meaningless. The value of information is a much bandied about concept. As with other intangible assets, such as brands, knowledge values are still somewhat uncertain but, as techniques spread and more comparisons of value become available, confidence and usage will rise rapidly. The demand for better measures of knowledge rises as donors and other stakeholders rightly require managers to justify the commitment of more and more capital to knowledge-intensive projects.

Some basic economics can help. Value is often perhaps best tested by seeing what some people are prepared to pay and what other people expect to charge. Economic theory indicates that competitive pricing will drive prices (and therefore perceived value) close to each other if competing "suppliers" have "perfect information" about the markets, products and /or services they supply. It is this theory that leads you to use competitive tendering to choose systems (see chapter 14). You can use the same type of thinking to value the entire initiative. Would it be cheaper and better buy in the service, the system or the information we want from a third party supplier rather than go to the bother of implementing systems ourselves. The advent of so many application service providers (ASPs), who provide just such third party services, often on a pay-as-you-go basis, indicates that IT suppliers believe that they have spotted an economic trend. With the world-wide-web as a possible delivery mechanism for applications, many organisations will find it more cost effective and beneficial to source the entire application and/or information provision from a third party supplier than to undertake the initiatives themselves in the traditional manner.

However, there are even more discriminating ways of assessing value than relying solely on competition theory and pay-as-you-go data charges for application services. Often, the perceived value (or lack thereof) in an IT initiative arises during the initiative rather than stated in the initial proposition. In other words, the huge cost overrun or the hugely beneficial spin-off arises while the project is running.

Basic economics can also help us to scope, control and value IT projects as they are going along. If we can estimate the marginal benefits and the marginal benefits costs of additional information, which might or might not form part of the initiative, we ought to be able to decide whether the additional information will provide net value. This might sound theoretical, but in our experience successful IT projects have to grapple with practical decisions around extending the scope of the initiative almost from day one. Each rescoping decision should involve some thinking about the net value (marginal benefits and costs) likely to arise from that decision. Whilst we accept that it is not possible to compute the value of information "to the penny" using such measures, we do advocate using hard measures as much as possible. For example, the amount of time staff spend using information arising from the initiative can be measured and indicates the value those staff place on that information.

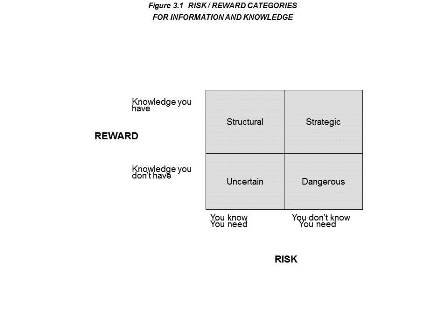

Risks and rewards of information management

A risk/reward categorisation of the value of information is shown below in figure 3.1. Knowledge is enhanced through:

- structural work where obvious information is enhanced: management information systems such as finance, fundraising systems, operational systems for service provision.

- Filling in uncertain areas where patterns need to be challenged and anomalies become paramount, for example information that enables practice learning for enhancing and revising service practice.

- Repairing dangerous areas of poor knowledge or gaps: donor information and analysis, market research of beneficiary perceptions, regulatory futures.

- strategic information, where thought and consideration are foremost in deriving value from existing information which has not yet brought value.

In the stable state, organisations find patterns of success and reinforce them. Information needs in such circumstances are probably stable and therefore have low marginal cost. Regular financial management information might fall into this category.

In the change state, anomalies indicate that established patterns are undergoing discontinuous change; the underlying paradigms shift and new patterns of success emerge. Information needs in such circumstances tend to change frequently and therefore have higher marginal cost. The tension between the stable and change states is key - timing is everything. If no effort is expended in enhancing knowledge, the knowledge base is probably of little value - an asset without anyone prepared to pay for maintenance is either eternal (e.g. a definition of your cause) or valueless (e.g. an incomplete slightly out of date list of health centres).The next chapter, goes into more detail on how to scope, manage and value knowledge management initiatives.

Summary

- The distinction between information systems and IT infrastructure is important, to enable us to determine who owns, pays for and co-ordinates the various components of our systems

- Make sure you are clear on who owns, pays for and co-ordinates each aspect of your IT.

- For most organisations there are grey areas where it is difficult to determine who should look after what - the purpose of thinking about these matters is to have clear responsibilities for costs and benefits.

- Depending on the size of your organisation and the complexity of its structure, you should establish appropriate management structures for the ownership, cost-allocation and co-ordination of information systems and IT infrastructure.

- Not-for-profit organisations should feel bound to try to value the benefits of IT, rather than the alternative, which is to spend the organisation's funds on IT in the vague hope that this IT spending will somehow advance the organisation's objectives.

- Use evidential methods borrowed from the world of audit (despite the surreal moniker COD-VERB).

- Where possible, use basic economics ("competitive" pricing theory, marginal costs and marginal revenues) to help you to value your use of IT.