Chapter 2: Needs, Wants And Prioritisation

Chapter objectives

In this chapter we shall:

- Worry about the fact that so many IT strategies are unachievable.

- Illustrate tools and techniques for separating needs from wants.

- Provide you with tips on prioritising IT opportunities within the constraints of your achievable resources.

What can really be done?

So many IT strategies that we see are unachievable wish lists. We frequently come across IT strategies that read a little like the spoof strategy in chapter 1, often in small not-for-profit organisations with limited resources that couldn't possibly achieve the ivory tower ideas.

The following case example is one of several in the book, which are reminiscent of actual examples the authors have come across.

Tools and techniques

There are many tools and techniques available to help with IT strategies. In part 4 we discuss communication, contribution, consensus and commitment (the 'four Cs') in more detail. Suffice it to say here that experience teaches us that the more collaborative and consultative techniques tend to be especially effective in the not-for-profit sector as long as the tools are applied well. The table 2.2 contains a non-exhaustive list, but includes the main tools we have found effective.

Case Example

A well-meaning trustee of "Save our Sprats" (SOS), a small but excellent charity, knows someone who is very high up in "MegaITcorp inc" (Mega). Mega are well known for building mission critical trading systems for the worlds biggest banks and exchanges. Generously, Mega assign one of their top business analysts to SOS to help them with their IT strategy. The analyst is a bright young thing, but she has never looked at any organisation employing fewer than 1,000 people before and uses the term "small budget" to mean anything between £100,000 and £500,000. Both of SOS's finance people are open-minded and keen to benefit from Mega's generous support. SOS employs 25 people and when the finance people use the term "small budget" they mean under £1,000.

The finance people are frank with the analyst, so she quickly identifies that SOS finds it problematic to match optimally calls for funding with its available restricted and unrestricted funds. Commodities traders have analogous problems matching tradable warrants with commodity trades. There are packages available which could help with this problem and they are relatively cheap. When the analyst says "this package is cheap" she means that a starter pack software licence can be had for £50,000 to £100,000. When the head of finance hears "the package is cheap" he hopes that the analyst means less than £100, although the head of finance has a sneaking suspicion that this "city type" analyst might mean as much as £500. "We'll probably need a day or two's training as well, so better put aside £1,500", thinks the head of finance.

Each limb of the IT strategy is developed in the same way, until it all comes tumbling down when SOS wake up to the price ticket on some of the more alluring ideas. Strangely, because the analyst has no experience of work with similar organisations, those more alluring ideas are probably wants more than needs; more immediate possible "quick wins" are overlooked in the flurry. Equally strangely, the Mega analyst's experience in large financial organisations could be incredibly useful to SOS if her knowledge was tempered with an understanding of SOS's context. Going back to the matching funds example, a day's work sitting alongside the accountant prototyping a spreadsheet model for matching funds would have delivered most of the benefits within the constraints of SOS's budget

Result: "the information we have isn't the information we want, the information we want isn't the information we need, the information we need isn't available". When you hear this mantra (or its equivalent), you know it's time to revise your IT strategy to take appropriate account of needs, wants and priorities.

Table 2.1 Tools and Techniques

| Tool / Technique | Main purpose /Description | Collaborative / Consultative? | Other comments | |

| Interviews (technique) | understanding objectives / identifying information needs / prioritising IT opportunities | consultative | time consuming | |

| Focus groups (technique) | understanding objectives / identifying information needs / prioritising IT opportunities | collaborative & consultative | popular and effective for charities | |

| Six thinking hats | encourage people to think broadly / initiate brainstorming | collaborative | good ice breaker (e.g. where focus groups are rarely used) | |

| Five forces models | helps to understand uniqueness & comparative advantage / stems from “competitor” analysis | collaborative | can be applied to many voluntary sector situations, but should be used selectively | |

| Value chains | understanding objectives | collaborative & consultative | values can be comparatively complex for charities | |

| Critical sets | identifying information needs | collaborative & consultative | often effective in focus groups – a key tool for IT strategy | |

| High-level data models | identifying information needs | consultative | usually to confirm rather than devise | |

| Potential IT opportunities | input for prioritising IT opportunities | consultative | often used to confirm and expand list rather than to initiate | |

| Ranking | prioritising IT opportunities | collaborative & consultative | often effective for reaching consensus on priorities, helping to gain commitment |

Critical sets

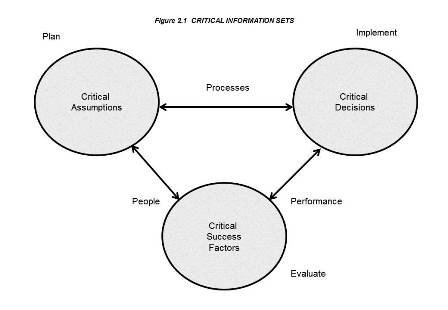

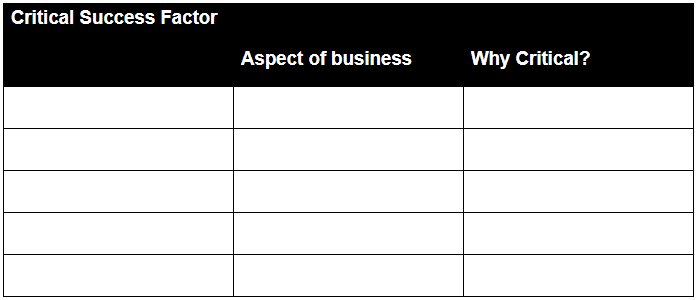

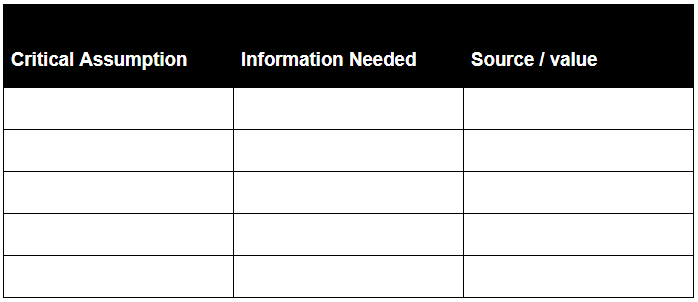

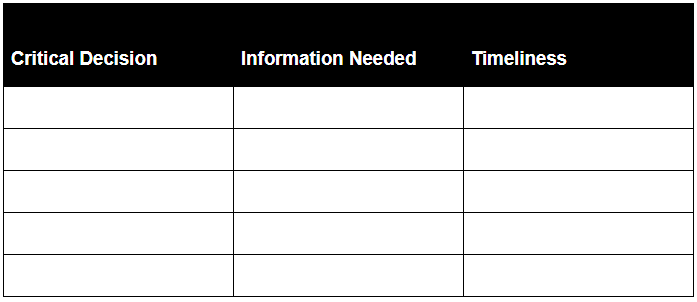

As an example, the diagram below (figure 2.1) shows the critical sets model. A charity needs sets of information to help it to measure whether it is meeting critical success factors (e.g. fundraising targets, number of people cared for). It also needs sets of information to help it to validate critical assumptions (e.g. the extent to which a disease is becoming more or less prevalent in society, poverty demographics and to help evaluate critical decisions (e.g. how many more nurses will we need in our care home this year, should we do a mail shot or a special event with our remaining budget). You can use the template tables below (2.1-2.3) the diagram to identify your main information needs in each of the sets &i.e. factors, assumptions, decisions). Focus groups can be a very valuable way of identifying the key information needs in each of these sets and in helping people within the organisation to divide to understand its differing information needs and varying purposes for information use. This form of analysis also helps organisations to divide up their information needs into definable and manageable chunks, e.g.. horizon scanning systems to help assess critical decisions and management information systems to help measure critical factors.

Template 1.2 Critical Success Factors

Template 2.2 Critical Assumptions

Template 2.3 Critical Decisions

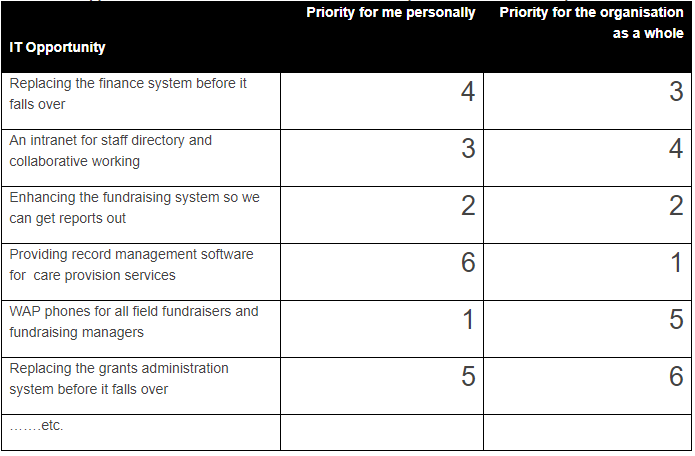

Ranking and prioritising IT opportunities

Once your IT strategy exercise has generated a great long list of things you want, you need to prioritise the ideas and decide which actions you are actually going to take. A simple tool to help with prioritisation is ranking. You force participants to rank the items on the wish list. An example is set out in the table below.

Table 2.2 Example Ranking Table

Rank the IT opportunities set out in the table, 1 = the most important, 6 = the least important

This form of ranking, simple though it is:

- Helps to stimulate discussion and debate.

- Ensures that participants pay at least some attention to all items.

- Helps the development of consensus.

- Shows participants that other parts of the organisation have different priorities.

- Focuses attention on the high priority opportunities.

There are risks to using ranking, not least:

- A false sense of scientific validity, as samples are often small, the judgement applied subjective and the options are not always clearly defined.

- Not all opinions have equal weight, but it would be courageous of you to try and weight the responses by seniority or depth of understanding!

- The answers are rarely conclusive. Having said that, the use of the second ranking column in the table above, "priority for the organisation as a whole", sometimes does uncover a remarkable level of consensus in not-for-profit organisations, where people have a propensity to think in terms of the common good.

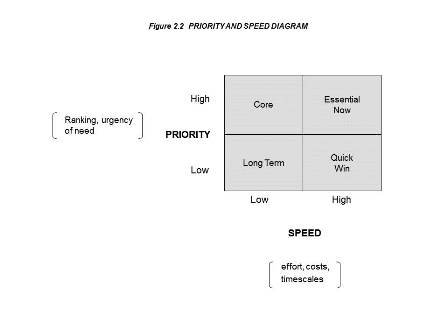

One further step is to get people to think realistically about possible speed of action. It might be possible to tackle a relatively low priority item and get a 'quick win', because that particular opportunity is low cost and low effort. In the example below, the basic intranet opportunity might be relatively quick and easy to achieve (assuming the infrastructure is in place), whereas the replacement of the finance system is likely to take a good deal longer. These projects could perhaps take place in parallel. Figure 2.2, below illustrates some of the thinking you might do with regard to priority and speed.

In order record your deliberations, you might set out your analysis under the following headings:

- Possible action: state the action you are considering.

- Further thoughts: implementation considerations.

- Onus: who is going to own this action.

- Priority: how high a priority is this action.

- Speed: how quickly do you need this action implemented.

- Estimated costs (ranges): how much money will it cost you.

- Estimated benefits (ranges): what are the tangible benefits of the action

- Estimated effort (ranges): how many days' work is involved.

Such a template might form the basis of your financial planning and is well on the way to being an outline action plan for your work programme is agreed. In larger organisations, your deliberations over the budgeting and project planning will of course go into more detail. For smaller organisations, analysis at this level can be a very useful route map for many months or even years.

Summary

- Make sure your IT strategy is realistic and achievable for your organisation.

- Encourage participants to be clear about what they need and what they want.

- There are many tools and techniques available to help you - we've listed many you can try.

- Critical sets is an especially useful tool to get people thinking clearly about their information needs.

- Ranking can help to build consensus and manage the thorny issues around prioritisation.

- When formulating your plans, remember that some opportunities are easier to achieve than others - such factors should inform your planning.

- This is not 'ivory tower' strategy - the results of such an exercise should be a pragmatic action plan for a hugely beneficial programme of work.